Third Thessaloniki Biennale

Staged against the backdrop of the continuing Eurozone debt crisis and the unfinished business of the Arab Spring, the Third Thessaloniki Biennale brought together works by some 70 artists and artist groups in venues across Greece’s second city – a place in which Hellenic, Byzantine and Ottoman heritages interweave, and (despite the efforts of successive West-facing administrations) the concepts ‘Europe’ and ‘the Middle East’ fray and unravel. In titling the Biennale ‘A Rock & A Hard Place’, curators Paolo Colombo, Mahita El Bacha Urieta and Marina Fokidis pointed both to Thessaloniki’s often occluded past, and to the various political and economic convulsions that currently grip the Eastern Mediterranean region, but did not offer, as their borrowed phrase might suggest, a counsel of despair. Instead, this thoughtful, often beautifully composed show was about productive friction – the sparks generated when the tectonic plates of difference and difficult choices grind against one another.

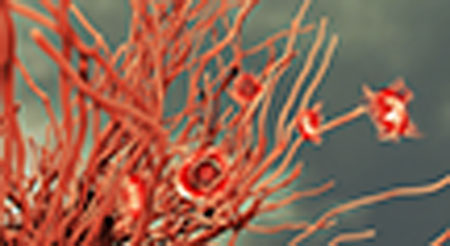

Three of the Biennale’s sites introduced contemporary works into historical collections. In the lobby of Thessaloniki’s Archaeological Museum, the spindly steel armature of Athanasios Argianas’s Song Machine 19 (2011) supported a looping strip of brass, onto which was etched a text describing space as measured by the highly contingent yardsticks of human and other bodies. To read these words (‘the length of a strand of your hair […] the width of a coral snake curled up’) was to wind your way around the sculpture at the speed of language, turning the experience of viewing it into an incantatory dance. Nearby, in Bruce Nauman’s Partial Truth (1997), the work’s title was etched into a heavy slab of granite, a monument to subjectivity – or its grave. Projected among fragments of classical architecture, Sifis Lykakis & Dionisis Kavallieratos’ video Artistique (2005) presents footage of what appear to be two archaic Kouri statues, staring impassively into camera until one pushes the other to the ground in a piece of purposefully slapdash slapstick that recalls a thousand YouTube clips. A less aggressive integration of the contemporary into the historical was to be found in the Museum of Byzantine Culture, where among the chalices and gilded icons, Katerina Athanasopoulou’s beguiling video Engine Angelic (2010) combined footage of abandoned industrial machinery with CGI to create a vision of a techno-organic godhead, half Duchampian Bachelor party, half new-age screensaver.

Katerina Athanasopoulou Engine Angelic, 2010, DVD still

In the State Museum of Contemporary Art, Biennale artists were shown alongside works from the George Costakis collection of Russian Constructivist Art. Papier-mâché Renaissance citadels from Spartacus Chetwynd’s performance Giotto’s Play (2004–7) shared space with photographs of Liubov Popova’s models of the City of the Future made for a 1921 Soviet mass spectacle, and the faded blues and whites of Kliment Redko’s canvas Dynamite (1922) were mirrored in Ali Kazma’s smart and funny video Jeans Factory (2008), in which Turkish workers apply identical signs of wear and tear to new pairs of ‘pre-distressed’ denims. Context to these juxtapositions was provided by Alexander Kluge’s extraordinary, nine-hour film News from Ideological Antiquity, Marx–Eisenstein–Capital (2008), which takes as its basis Sergei Eisenstein’s unrealized plan to adapt Das Kapital (1867) for cinema by way of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922). Identifying the rocks and the hard places here (the past and the present? Ideology and art? The promises and betrayals of communism and capitalism? The epic length of Kluge’s film and the strength of one’s bladder?) offered endless, dizzying and deeply enriching work.

Perhaps the Biennale’s strongest suit was three shows in which the members of its curatorial team flew solo. In the Casa Bianca, an early-20th-century mansion, Colombo presented an homage to haute-bourgeois literary taste and psychological anxiety featuring Christiana Soulou’s tense, kinky drawings of Shakespearean fairy folk from 2008 and the dreamy 1940s photographs of surrealist poet and psychoanalyst Andreas Embirikos. A harder edge was provided by El Bacha Urieta’s show at Yeni Djami, the highlight of which was Nikolaj Bendix Skyum Larsen’s Ode to the Perished (2011), a cluster of cocoons suspended from the former mosque’s dome made from ‘crisis concrete’ (a building material employed in war and disaster zones), that brought to mind the bodies of immigrants drowned in a desperate sea crossing. Best of all, though, was Fokidis’s exhibition at the Alatza Imaret, another former mosque and hospice that takes its name from its once-colourful masonry. In a pitch-perfect selection of searingly chromatic works (among them Pae White’s 1998 ‘Summer Samplers’ series of spider webs applied to bright sheets of paper, Panos Koutrouboussis’s late 1960s sci-fi drawings of the gaudy dusk of the age of Aquarius, and Yorgos Sapountzis’s contemporary ‘remaking’ of the venue’s smashed minaret from scrap fabric and scaffolding tubes) fresh colours breathed through the building, and a set of future histories began to gather. Between a rock and a hard place, it seems, a rainbow may nevertheless slip.