The Thirteenth Fairy

Artist Kerstin Brätsch and filmmaker and writer Alexander Kluge speak to Pablo Larios about algorithms, fortune-tellers and stained glass windows

Artist Kerstin Brätsch and filmmaker and writer Alexander Kluge speak to Pablo Larios about algorithms, fortune-tellers and stained glass windows

Pablo Larios Legend has it that the Frauenkirche, the cathedral in Munich close to where we are speaking today, was funded by the devil on the condition that it be built with no windows. Upon its completion, the architect invited the devil inside, who stood on a spot where no windows could be seen. But, on stepping away, he realized that he had been tricked – there were windows after all. In his fury, he left the black footprint on the church floor that remains today. What was it about stained-glass windows, Kerstin, that inspired you to work with the form?

Kerstin Brätsch The stained-glass works I showed this summer at Munich’s Museum Brandhorst are repurposed, disused remnants of windows made by Sigmar Polke for a Zürich church. Glass is light-dependent; in darkness, it becomes dead matter. It is simultaneously an archaic and current technology. We’re surrounded by glass everywhere today – architecture, computer screens, smartphones – and medieval windows once played a similar communicative role: telling stories to people who couldn’t understand Latin or read the bible.

PL The legend about this church, Alexander, reminds me of your 2003 book The Devil’s Blind Spot, which begins with a section on the devil’s acts. You once wrote: ‘The unfilmed criticizes what has been filmed.’ Do you feel this applies to other arts, too?

Alexander Kluge This goes for all the arts. Unsettled history lives on. The non-narrated and forgotten reality takes revenge. A story: in 1918, a German entrepreneur purchased a large inventory of lethal gas left over from World War I. In 1928, a portion of it was sold to the Soviet Union. Workers in Hamburg were poisoned while loading it to be shipped. Carl von Ossietzky, a German journalist, discovered and publicized this ‘illegal state secret’ in 1929. He was arrested and charged. As he sat in jail in 1933, he was further prosecuted as a Jew by the Nazis. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1935 before his death from tuberculosis, compounded by the abuse he suffered in the concentration camps, while in police custody in 1938. The remainder of the gas was buried and forgotten; the entrepreneur died. In 1977, a group of children were found dead. They had played on the ground where the gas was buried, next to a kindergarten to which the land had been sold. The noxious commodity from 1918 didn’t stay still. The container rusts, gas leaks out and kills. That is the way reality tells its stories. Narration by the arts should be equivalent to the power of facts.

PL What facts have you learned from one another by making works together?

KB Alexander is a major figure in German culture, whom I have always admired. In his treatment of history and grand narratives, he is able to present a doorway into the past through a personal experience, which is uncommon today. He is a rare character: a monolithic chronicler of our times and of forgotten knowledge.

AK I belong to the circle of the Frankfurt School of critical theorists. They called their building in Frankfurt ‘The Institute’, so I was proud to see Kerstin launch her own institution, Das Institut, in New York. This was a first impression. When Kerstin showed me some of her glass works, we decided immediately to collaborate. Our first work relates to Giuseppe Verdi’s opera, I due Foscari [The Two Foscari, 1844]: a terrible story by Byron about a Doge of Venice who has to kill his own son due to political obligations. Opera unifies music, art, text – a happy constellation, seen through Kerstin’s glass piece.

PL I see both of you as anachronists, working with historical material and media to comment upon the instability and contingency of history through to the present day. Kerstin, your recent museum exhibition in Munich, ‘Innovation’, includes works that are – in your words – ‘unstable’, as well as some of the glass pieces Alexander used for his films. How are these linked?

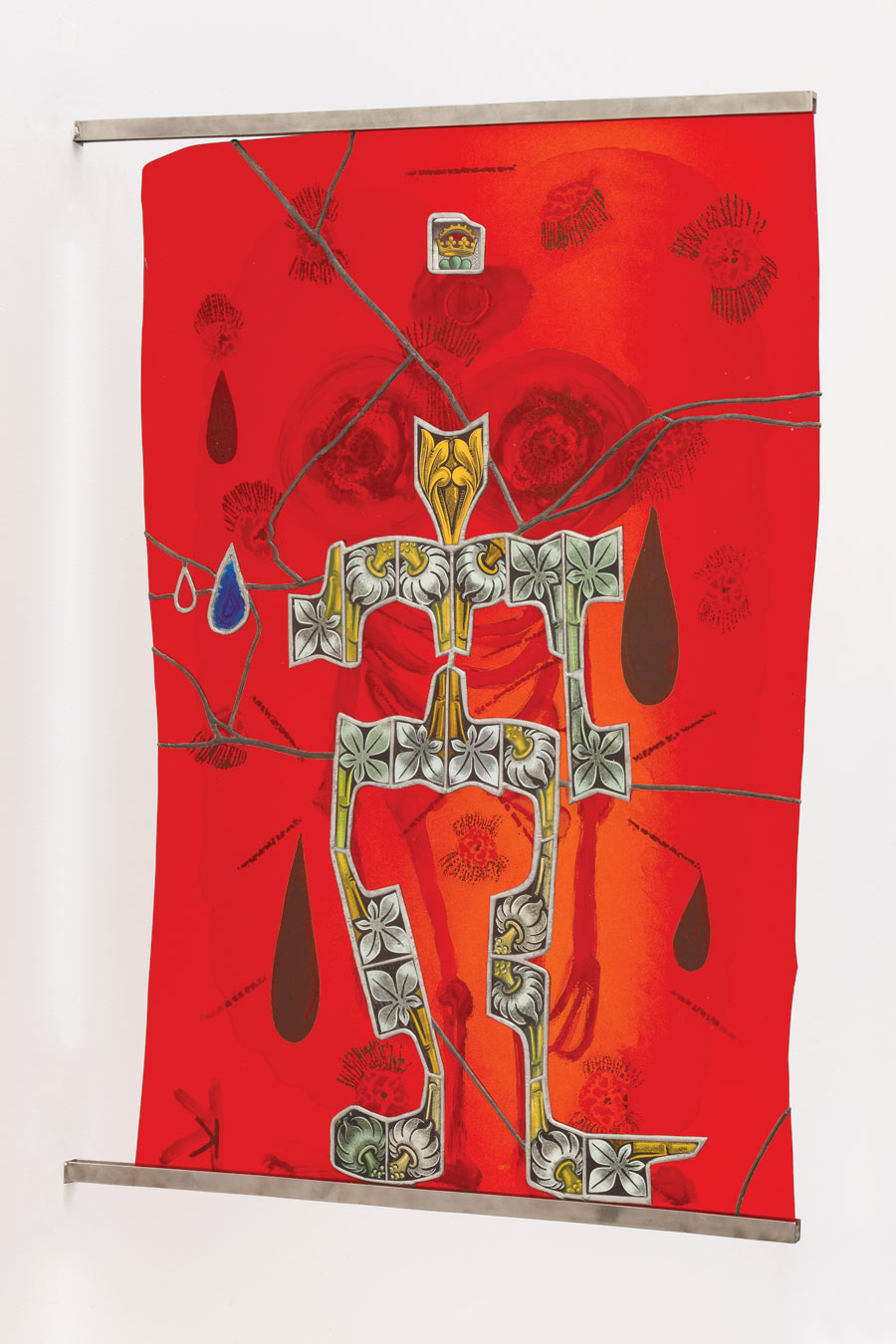

KB Within works such as the 2014 series ‘Unstable Talismanic Renderings’, I attempted, through marbling, to create an image on a moving background. This is something process-specific, alchemistic. You can’t manipulate the physical laws of the universe; you can’t rediscover ‘adhesion’ or ‘gravity’ as an artist. But you can replace brushstrokes with drops; you can make, deliberately, errors of translation. When Alexander uses my glass works there’s a similar transformation: glass stops being material and becomes a lens, a medium.

AK Kerstin taught me that if I look through the eye of someone else and film it, then it becomes cinema. An optic lens is normally transparent glass. But a work of art is like a person. So, when I film someone’s works, I see through the eyes of someone else. With four eyes, I’m a complete person. Today, we have a tyranny of image-realism, enforced by commercial cinema and mass-media: everything must cohere, make sense and resemble ‘reality’. But this reality is sometimes fictional, a phantasm. Film is the 120-year-old stepchild of art; its wonderful history is stifled by the persuasions of the ‘real world’ and the culture industry. Cameras could film much better using crystals, but we don’t do this due to the realism demanded by the media. Donald Trump, who comes from the entertainment industry and then brings this experience into politics, creates a dangerous, new imaginary reality. Yet, this reality belongs to our reality, too. That is why art should behave anti-realistically.

PL Kerstin, tell me about the air compressors in the first room of your exhibition – do they point, in a way, to the noxious gas of history, to borrow Alexander’s image?

KB The image visible in the first room of ‘Innovation’ is an airbrushed advertisement for a real company: Brätsch Compressors. It was my grandfather’s company (now my cousin’s). I borrowed their slogan: ‘Innovation’. What would it look like to market an unstable innovation? My paintings, hung over murals, connect to machines, giving the impression that they were machine parts or mechanical elements of the compressors. A compressor is a machine that compresses and generates pressure. How can it function beyond being a seamless capitalist product? The same could be asked about art: how does art function without being a seamless capitalist product?

AK But your ‘compression’ relates to film, too. The film camera is a light compressor that attempts through glass – an optic, a shard – to record the world. Within a compressor, there ‘live’ about 100,000 people who have put part of their lives into the production of the machine. This is also true of a bomb that falls on Aleppo: there are billions of particles of human life in it. Karl Marx called this the ‘dead labour’, in contrast to the living work of the worker. Art is not made to order; it cannot be custom fit. And art is not identical with what is preserved in the museums. Here’s another error of reading: the original Noah’s Ark did not contain animals but scriptures, which reached Mount Ararat. We need, if you will, a new Noah’s Ark. And, today, we must build a ship together again in this very angry lake of modernity. Shipbuilding – navigation, setting sail – is the task of the arts. And collaboration is very good for this. That is true of your machine affinity, Kerstin, which I understand concretely.

KB Working within industry, I play with labour in relation to art. By engaging with trades and crafts that I don’t completely understand, I necessitate a collaborator – an expert in the field – to make the artworks. I also like to think that the work is a force in preserving knowledge. Das Institut involves forms of real collaboration but, ultimately, it is a fiction: it is actually only a notion of a field or, like you say, a raft, a ship, where we can meet and exchange ideas with one another.

AK In the beautiful, stately exhibition ‘Postwar: 1945–65’, at Munich’s Haus der Kunst, there was not a single piece of music or any philosophical or literary texts. The art in this museum did not interact with other kinds of art. During the Renaissance, this was different. And the urgency of our time makes us consider the necessity of a renaissance in the 21st century. We have to co-operate across different kinds of art. That is the meaning of ‘innovation’. You see, art is never simply image-realistic. Subjectivity protests against pure reproduction. We don’t think: a page is a page is a page. We think: this is a piece of paper, my grandmother had one, too, and in the year 1929, a piece of paper was a different thing than in 2017, an electronic age in which it is anachronism. We think entirely prismatically. With Kerstin’s works, I can step outside of image-realism and enter into the year 1929 with images that are from today and from 1929. An image from 1929, for a normal observer is always-already old, historical. But nothing about the events of 1929 is historical: that was the last year in which one could have prevented Hitler rising to power. It was the year of Black Thursday. The experience of this year is relevant for 2017 and will influence the future.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 8.5px Times}

PL Kerstin, the earliest works in ‘Innovation’ were made with the assistance of fortune-tellers. Did your interest lie in telling the future or in engaging with the atavistic, the past?

KB The ‘Psychic’ series (2006–08) of works on paper, which were juxtaposed with the more recent ‘Unstable Talismanic Rendering_Psychotrops’ (2016), were painted in the US. When I first arrived in New York, I had my palms read by fortune-tellers there. What kept coming up was that I had a ‘dark’ aura and needed healing. I oscillated between total belief and doubt in what they were saying – an oscillation that found its way into painting and, eventually, into glass-blowing and marblization: highly technical crafts that you cannot fully control. This mixture of reason and irrationality was also very telling about the contradictory nature of a place like New York, the capital of capitalism. People get desperate in the rationality of the capitalist system and look to mysticism or pagan rituals to heal the wounds that this rationality inflicts. The current political climate in the US is one ugly side of this phenomenon: people cling to the non sequiturs of a lunatic like the current president. When you become inundated with made-up narratives about the world, you don’t know what to think anymore, and everything then becomes believable: a fake news drip that leaks out everyday.

PL Alexander, many of your projects have engaged with similar dimensions of work and capitalism. Your first solo museum show, at the Museum Folkwang in Essen, will include a section on ‘labour’. And, recently, I saw your 2017 film Scenes from the Working World at the Fondazione Prada in Milan.

AK Scenes from the Working World is a short film based on the fact that Rainer Werner Fassbinder was once given a filming licence for a factory. Because he was not familiar with factories, he decided to film words relating to activities that are not work. It’s not easy. It’s an interesting mirror, for example, to say: ‘Dying is not working.’ ‘Sleeping’, Fassbinder says, ‘is not working.’ By extension, is moaning or telling jokes labour?

PL It seems to me that Silicon Valley has now blurred, in a devastating way, the boundaries between ‘play’ and ‘work’.

KB Today, we are always connected to our phones, our online personas, which means we are always working for someone else. Everything that could be seen as play becomes work, in a real way, when uploaded to the platforms that magnify their reach.

AK In my short story ‘Sirens in the Age of Technological Reproducibility’, I connect Walter Benjamin’s ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ [1935] with the ability of strong digital media and Silicon Valley to guess what our libido wants – even sooner than the libido itself knows. And they can do it. This is not only relevant for children, but also for old people like myself. Amazon meets your needs. This is like a fortune-teller. Yet, Silicon Valley is not omnipotent. I made a film recently that describes an observation by [radical feminist and former factory worker] Marianne Herzog: a female worker does manual labour and always, after a certain time, makes sweeping, wing-like gestures, like a bird, before continuing. Only in this way can she withstand mechanical labour: a person is a machine and an anti-machine at the same time.

KB Art can do this, too.

AK Yes, I believe that, in terms of Silicon Valley, we together, as artists, have the anti-algorithm in mind. In the Grimm Brothers’ fairy tale of Sleeping Beauty, a king begets a daughter but, at the celebration of her birth, there’s only enough crockery for 12 fairies as guests, so the 13th fairy is excluded. She curses the castle and it falls into a 100-year sleep. An algorithm from Silicon Valley has great advantages, such as very good accuracy, like an arrow. But, in making everything universally applicable and powerful, an algorithm expels the 13th fairy. We artists are the collectors of the expulsed. We’ll collect all of it again – otherwise, the excluded runs around as a ghost. Today, we must collect ghosts anew and bring them out into our industrialized jungles. Kerstin and I tend to be friendly to these ghosts.

KB And for that we need windows, too.

Translated by Pablo Larios

Main image: Kerstin Brätsch,‘Innovation’, 2017, exhibition view at Museum Brandhorst, Munich. Courtesy: the artist and Museum Brandhorst, Munich; photograph: Uli Holz