The Top 10 Shows in the US of 2022

From a show of Ukrainian women artists at Fridman Gallery, New York to Kaari Upson's first posthumous exhibition at Sprüth Magers, Los Angeles, here are the best shows of the year

From a show of Ukrainian women artists at Fridman Gallery, New York to Kaari Upson's first posthumous exhibition at Sprüth Magers, Los Angeles, here are the best shows of the year

‘What could this much mass despair and revolutionary strength look like,’ Margaret Kross wrote in her review of the 58th Carnegie International in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, ‘except for a magnitude exceeding individual comprehension?’ The exhibitions rounded up here are characteristic of important themes in American art today – including efforts to de-centre the US. ‘Women at War’, a collaboration between New York’s Fridman Gallery and the Voloshyn Gallery in Kyiv, Ukraine, showcased work by Ukrainian women, some of which was made after Russia’s invasion earlier this year. Carolyn Lazard’s solo show at the Walker Art Center considered themes of gender, race and disability through a cleverly discursive installation on dance. Other exhibitions centred tender pictures of friends, families and strangers, whether in Wolfgang Tillman’s photographic mode or Gideon Appah’s fantastical paintings. Here are – in no particular order – some of the strongest shows of 2022 from across the United States.

‘Life Between Buildings’

MoMA PS1

New York, USA

In the 1970s, New York City began a campaign of disinvestment from and privatization of open spaces. As so often in this city’s history, artists stepped up, cultivating gardens and green spaces that continue to flourish decades later. ‘Life Between Buildings’, a group show at MoMA PS1, explored this under-regarded history, proposing ‘new modes of creating value’, as Maxwell Smith-Holmes wrote in his review. Some highlights from the exhibition are Danielle De Jesus’s acrylic-on-dollar-bill paintings, which depict the flourishing of the Puerto Rican diaspora among Bushwick’s community gardens, as well as the looming threat of displacement by developers for whom green spaces are more reason to gentrify such neighbourhoods. The exhibition taps a rich vein in the city’s art scene: anonymous gallery sited artworks across community gardens this summer, and spaces like Socrates Sculpture Park continue to mount excellent shows in public spaces.

‘Is it morning for you yet?: 58th Carnegie International’

Carnegie Museum of Art

Pittsburgh, USA

The longest-running exhibition of art in North America returned this year with its 58th edition, combining pieces from international collections with new work. Curated by Sohrab Mohebbi, the plaintive yet hopeful title of the exhibition – ‘Is it morning for you yet?’ – is borrowed from a Mayan Kaqchikel expression for ‘good morning’. It’s a fitting title to anchor a show that spans time zones, histories and geographies to untangle the ugly effects of US imperialism. I was particularly struck by Pio Abad’s dive into the Carnegie Museum’s history, echoing the visual language of the museum’s facade as he reproduced a letter in which the museum’s founding patron and namesake, Andrew Carnegie, sought to purchase the Philippines for US$20 million. The plethora of micro-shows, often guest curated, renders this edition particularly successful. Hyphen –’s section introduced me, and I imagine many others, to the lyrical paintings of the late Indonesian artist Kustiyah, while Kross was compelled by works from the collection of Fereydoun Ave, including, she writes, ‘sumptuous kitchen still-lives by Leyly Matine-Daftary, who… “transformed her home into a sort of bohemian haven”’.

Wolfgang Tillmans

The Museum of Modern Art

New York, USA

Given Wolfgang Tillmans’s ubiquity in and outside of the art world – he is perhaps best known for the cover of Frank Ocean’s album Blonde (2016) – we went with a more subtle work for the cover of our September issue. In Still life with Juan Pablo’s tree (2021), shadows fall over the velvety stalks of plants; a crystal light glints from a glass of water. The image is Tillmans’s tribute to his assistant, close friend and collaborator Juan Pablo Echeverri, a Colombian visual artist who tragically passed away earlier this year. Tillmans’s show at The Museum of Modern Art, ‘To Look Without Fear’, spans the breathtaking range of his three-decade photographic career, from raucous images of parties to still lives and abstract experiments. ‘I somehow have this sense of history – of the now being history,’ Tillmans told Jeremy Atherton Lin in his profile of the artist for our September issue. His friendships and relationships are an immanent presence in his work: celebrities, friends and strangers alike are subject to the same quiet, probing interest.

Carolyn Lazard

Walker Art Center

Minneapolis, USA

‘There’s this false notion that if you make art which is tied to or interested in the world and in social conditions, you don’t care about its aesthetic value,’ Carolyn Lazard told Edna Bonhomme in a feature for our March issue. ‘I’m deeply invested in beauty; I just don’t see the aesthetic value of art exclusively [in] the relationship between the art viewer and the art object. It’s everywhere: in ideas, gestures, actions, care.’ Lazard translates that expansive sense of aesthetics into their first institutional solo show in the United States, ‘Long Take’, at the Walker Art Center. The exhibition is anchored by a sound installation that teases out themes of gender, race and disability through an exploration of the legacy of dance, unfolding largely through sound: an audio description, and the soft rhythms of the dancer’s movements and breath. If you missed the Walker’s version, look out for the ICA Philadelphia’s showing in 2023.

Suzanne Lacy

Queens Museum

New York, USA

In his review of Suzanne Lacy’s thematic survey at the Queens Museum, Travis Diehl points out the difficulty of launching a retrospective of this kind: the ‘gap between the active, catalytic artwork of the past and the more-or-less nonreactive present archive’. The bulk of Lacy’s work lies in organizing intimate conversations between women. In International Dinner Party (1979), her collaborators communed in locations around the world, then sent her details via telegram. The distinctly pre-internet documentation and ephemera that populate the show require the audience to exercise prodigious imagination to activate their responses, but reward us with forthright and often-moving insights. ‘Again and again,’ Diehl writes, ‘documentation of Lacy’s projects includes the refrain: “I’m not alone in my pain.”’ Lacy might achieve this effect by meeting subjects on their own terms, shaping these works through gentle guidance rather than organizing them under the aegis of a set vision. For Doing Time (1993), she invited inmates at a high-security women’s prison to design a series of themed cars. An ‘abuse’ car was filled with household objects and text by the inmates describing how such objects had been used against them in acts of brutality. There was a ‘healing’ car too; ruined on the outside, but filled with photographs and tender personal possessions.

Gideon Appah

Institute for Contemporary Art at VCU

Richmond, USA

Ghanaian artist Gideon Appah made his US institutional debut with ‘Forgotten, Nudes, Landscapes’ at the Institute of Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University. His paintings hum with a surreal energy. His figures, Simon Wu writes, come across as ‘ghosts of clubbers in some primordial land’; certain paintings draw on myth, and incorporate symbols that evoke tarot or shamanic imagery. The influence of Black portraitists is palpable: men clad in white suits recall figures in the paintings of Barkley L. Hendricks, for example. ‘Produced quickly and at high volume,’ Wu writes, ‘the works have a provisional, immediate quality reminiscent of digital engagement.’ Indeed, Appah has drawn on a rich array of demotic sources for the newly-commissioned works in this exhibition, with characters culled from Ghanaian movies and Appah’s friends, set in locations that are sometimes ambiguous – as in the constellation-cum-nightclub of Remember Our Stars (2020) – and sometimes specific, as in Ghana’s famed Roxy Theatre in Roxy 2 (2020–21).

‘Women at War’

Fridman Gallery

New York, USA

Co-presented by New York’s Fridman Gallery and Kyiv’s Voloshyn Gallery, ‘Women at War’, curated by Monika Fabijanska, features works by contemporary Ukrainian women artists. Though a few of the pieces on view postdate Russia’s February 24 invasion, the show argues for a longer view of the conflict between the two nations, including Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the fallout from the USSR’s collapse. ‘Ukrainian artists are… faced with the unique pressure of defining their cultural opposition,’ Zoë Hopkins writes in her review, ‘as well as stewarding a contentious historiography.’ Fabijanska’s decision to feature exclusively women is another invocation of lesser-seen narratives. In what ways, the exhibition asks, is war gendered? Though women are largely missing from chronicles of conflict, a quarter of the Ukrainian armed forces are women: the work here foregrounds the struggle to define a specifically Ukrainian and Eastern European feminism, wrestling with notions of agency and victimhood. Hopkins highlights Alevtina Kakhidze’s Strawberry Andreevna (2014–19), which tells the story of her mother’s death after their separation by war, in a series of images that are painful but nevertheless unmistakably playful, ‘unfold[ing] across the gallery wall like a comic strip… bristl[ing] with witty resilience against war’s capacity to crush the imagination’. Whether or not you had the chance to see the show, don’t miss Fabijanska’s deeply researched essay for the exhibition catalogue.

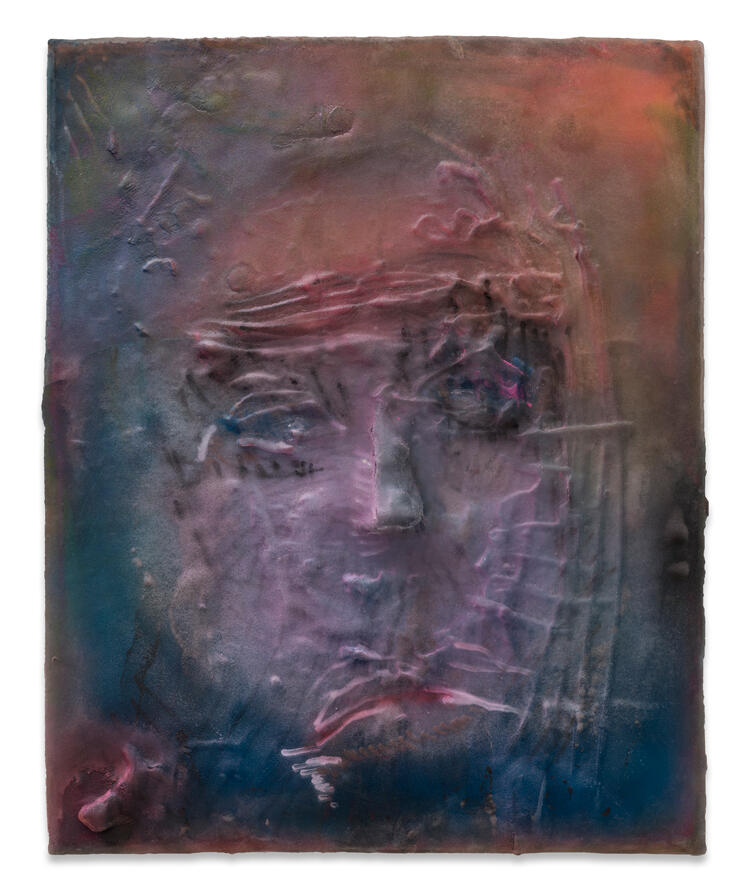

Kaari Upson

Sprüth Magers

Los Angeles, USA

Kaari Upson passed away last year at the age of 51. The California native’s dark, beatific and wholly distinctive body of work drew on her own experiences, as well as the lives and stories of strangers. Jonathan Griffin first met Upson in 2011 for a profile for this magazine; 10 years later, he penned her obituary. ‘There was no one like her,’ he wrote, ‘as an artist or as a person.’ It’s fitting, then, that he returns to these pages to review ‘never, never ever, never in my life, never in all my born days, never in all my life, never’, her first posthumous exhibition at Sprüth Magers, Los Angeles. Griffin points out how Upson’s work repeatedly subverts easy narrative arcs: though a posthumous show, she had a hand in planning it, and even named it. Though it seemed as if pieces from her series ‘Portrait (Vain German)’ (2020–21) documented a descent following a terminal diagnosis, they refer by name to her mother rather than herself. Griffin invites us to look more closely at a series of untitled paintings Upson began during the pandemic. Favoured motifs recur throughout these pieces – blonde women, checked fabric – but they reveal a more formally experimental side to Upson, with sections of both masked and washed canvas and imprints of other paintings. ‘The best of them are gorgeous, funny, lush and disturbing,’ Griffin writes, ‘all at the same time.’

‘52 Artists: A Feminist Milestone’

Aldrich Museum of Art

Ridgefield, USA

In 1971, Lucy Lippard curated the groundbreaking ‘Twenty Six Contemporary Women Artists’ exhibition at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, presenting a survey of emerging artists working in New York City. More than 50 years later, many of those ‘emerging’ artists have now gained international acclaim: Lippard’s checklist included Alice Aycock, Howardena Pindell and Adrian Piper. ‘52 Artists’ – also at the Aldrich – includes some reprisals: Piper and Pindell contribute works they exhibited decades before, but also new pieces that track the development of art through their individual practices. In her review of the show, Erica N. Cardwell points out that Pindell’s Carnival, Bahia Brazil (2017), which consists of ‘cut-and-sewn canvas with disparate yet connected lines dotted across an energetic lavender palette’, traces a clear trajectory from her seminal Untitled (1968–70), in which stuffed and rolled canvases ‘elevated the concept of “work in progress” into a radical new take on sculpture’. Among emerging contemporary artists, Cardwell was struck by LaKela Brown’s Composition with 35 Golden Doorknocker Impressions (2021), which, she writes, ‘disrupts an artworld that remains predominantly white by imprinting an array of doorknocker earrings – an aspect of Black American cultural aesthetics – in white plaster, then picking out 35 in saturated gold, restoring its polished sheen’.

Henry Taylor

The Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles

Los Angeles, USA

‘B-Side’ is the largest survey of Henry Taylor to date, presenting three decades of his career through more than 150 paintings, drawings and sculptures. Taylor’s paintings, mostly of Black people – family members, friends, idols, celebrities, and those who were murdered by police – incorporate charcoal, collage and chalky acrylics that can mirror oil pastel in its vibrancy. Our senior editor, Terence Trouillot, profiles Henry Taylor in an upcoming feature for the January/ February issue of frieze; he was ‘floored by the sheer grit and tenacity of his brushwork’. One of the highlights of the exhibition for Trouillot is Warning shots not required (2011), a more-than-six-metre long canvas of Stanley ‘Tookie’ Williams, who founded the Crips gang, and later advocated for greater anti-gang education. It is, he writes, ‘an oneiric vision of carceral life.’ Also on view are Taylor’s lesser-seen sculptures, including a new series Taylor dubs ‘afro trees’: ‘towering conifers with nappy, synthetic black hair for foliage.’

Main image: Thu Van Tran, Colors of Grey, 2022, installation view. Courtesy: the artist and Carnegie Museum of Art; photograph: Sean Eaton