Very Superstitious

Consumerism emerges as a modern form of superstition in the Ars Baltica Triennial in Berlin

Consumerism emerges as a modern form of superstition in the Ars Baltica Triennial in Berlin

Roman emperors, we’re told, based important decisions on omens divined from the entrails of birds. For centuries, defining certain human behaviours as ‘sin’ or ‘heresy’, believers handed their neighbours over to church torturers and executioners with a clear conscience. But our consumer era – the end of history – represents the end of superstition, doesn’t it? We live now in an era of rational, informed choice, don’t we?

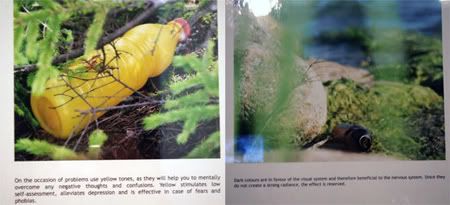

Maybe not, thinks Katrin Tees, an Estonian artist showing her amusingly pointed photographs in ’Don’t Worry — Be Curious!’, the 4th Baltic Triennial of Photographic Art, currently on show in Kreuzberg, Berlin. In the series ‘Handbook of Creative Littering, Advanced Level’, Tees takes the dogmas and superstitions of consumerism – the ideology of the market economy Estonia has recently emerged into – as her subject. Photographs of consumer trash lying in idyllic country settings are captioned with priggish ‘rules’ borrowed from new age marketing.

‘On the occasion of problems,’ runs the caption to a photograph showing a yellow bottle of cooking oil discarded on a forest floor, ‘use yellow tones, as they will help you overcome any negative thoughts and confusions. Yellow stimulates self-assessment, alleviates depression and is effective in case of phobias.’

A photo of a brown glass bottle flung down at the edge of a lake is captioned: ‘Dark colours are in favour of the visual system and therefore beneficial to the nervous system. Since they do not create a strong radiance, the effect is reserved.’

The confident waffle of colour theory is backed up by the assertions of psychology: ‘Seeing only monochrome colours will in the long run radically tire our eyes and drain certain colour-sensitive cells,’ runs the caption under a photo of a discarded carton of fruit juice. ‘That will make one inactive and depressive. To balance the situation, different tones should be added in order to activate other colour-sensitive cells.’

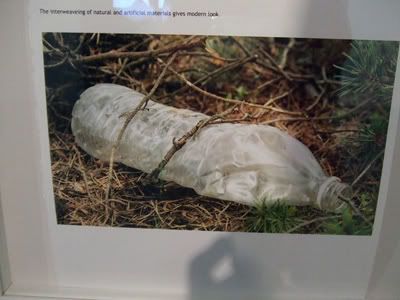

And a crushed plastic mineral water bottle despoiling a lake is captioned: ‘Soft and neutral colour schemes are especially kind to our eyes and express natural simplicity. Favoured by those who like to design surroundings at ease yet in style, without a struggle.’

In these softly assertive statements – this odd synergy between professionalism, pseudo-science, faith healing, P.T. Barnum bullshit, professional arrogance, hype, rhetoric, appeals to authority, Chinese Whispers, charismatic healing, pragmatism and marketing – we recognize the superstition of the consumer era; the rhetoric we hear from salesmen, commentators, economic analysts, experts, and yes, even people who write online columns of art criticism. Some gets trapped in our cynicism filters; the rest trickles down into circulation as ‘common knowledge’ and kaffeeklatsch folk wisdom.

Katrin Tees is part of a group who call themselves the Infotankers. Highly skeptical about Estonia’s booming new consumerist era, the group emerged five years ago from the Estonian Academy of Arts. Puncturing the intrusive commercial messages cluttering Estonia’s landscape with satire, they’ve compared their project to Adbusters, whose founder, Kalle Lasn, was born in Tallinn. Like Lasn, the Infotankers make an explicit parallel between the ecological environment and the cultural one: both can be polluted by consumerist trash, and both need to be reclaimed and purified.

Looking at Tees’ photographs in the NGBK Gallery in Kreuzberg – a Berlin district we could safely call reflexively, almost institutionally, consumer-cynical, but also more-than-usually likely to succumb to the charismatic counter-offensives of aromatherapists, holistic healers and organic dieticians – I got to wondering who this ‘handbook of creative littering’ was satirizing. The answer fell uncomfortably close to home; anyone, it seems, who’s sick of both consumerism and the moronic cynicism it fosters. Anyone who, exhausted by resistance to endless commercial pressure, suspends their critical thinking long enough to let some charmingly ‘alternative’ professional answer the wearying epistemological question, ‘Who says so, and how do you know?’ with the mesmerizing answer, ‘I do, I just do, trust me.’

The Infotankers’ thorough knowledge of the mechanisms of bullshit could make it tempting for them to turn coat, though – especially if they suddenly find themselves in need of cash (it does happen to art school graduates). Tees has already staged a performance (Let’s Play Objects and Subjects in the 21st Century) in Tallinn’s Kaubamaja department store. Let’s just hope we don’t find these iconoclasts of the discarded plastic bottle, these puncturers of modern superstition, five years down the line, working in marketing. It wouldn’t be the first time idealistic satire turned out to be pragmatic cynicism’s clip-on training wheels.