The Whole Thing

British artist David Batchelor talks to Cuban-American painter Carmen Herrera about her 80 years of making art

British artist David Batchelor talks to Cuban-American painter Carmen Herrera about her 80 years of making art

This conversation took place over the course of an afternoon in Carmen Herrera’s studio in New York. I became intrigued by Carmen’s work after I saw her exhibition at IKON in Birmingham, UK, in 2009; I was embarrassed that I hadn’t been aware of it before. Ever since I was a student, I have had a thing about the more austere forms of abstract art, and there I was, faced with a body of work that spanned the entire postwar history of abstraction. Even better than that, almost all of it used just a few lines and no more than two colours. Carmen’s studio occupies the south-facing end of her long, narrow, seventh-floor apartment in lower Manhattan, where she has lived and worked for 45 years. The studio and apartment are functional and uncluttered, orderly but in a straightforward and unstudied way. Carmen herself was warm and gracious, funny and entirely without pretensions. She has the relaxed dignity that comes from a lifetime’s work and the understanding that she has absolutely nothing left to prove. I would like to thank Tony Bechara, Carmen’s long-term friend and neighbour, who helped organize and facilitate this discussion.

David Batchelor You were born in Cuba in 1915.

Carmen Herrera Yes, but I left when I was very young, and although I went back a couple of times for family crises I never lived there again. If I went to Havana now I wouldn’t know anybody.

DB How old were you when you began painting?

CH I was a child prodigy as far as my family was concerned. I had a brother who was a painter, a very talented person who did nothing with his talent, but through him I became interested in art. My family were collectors of paintings, but not of modern art.

DB Your work was first exhibited as part of a group show in 1933 at the Círculo de Bellas Artes in Havana.

CH It was a funny exhibition, because they weren’t prepared for the kind of work I was doing; it was amusing to see people come, look and walk right out, as if they had been insulted by me.

DB You were also included in an outdoor exhibition in Havana in 1936.

CH Yes. We hung our paintings in the trees and people came in their droves. It was shortly before World War II; some German sailors were in Havana and came to the exhibition. I had placed the head of Christ in a swastika in one of my paintings, because the Germans were crucifying Christ, but the sailors didn’t know how to respond. It was terribly funny. The things you do when you’re young!

DB Then you moved to New York with your family in 1938.

CH I came with my husband [Jesse Loewenthal] – an American I had met in Havana. But I had been to Europe in 1928 and went to school in Paris and learned how to massacre French! I then went to Berlin in 1929. It was weird; there was something there that was not right somehow. Children are like dogs – they know. First, I was sick and then my sister was sick. We realized something was going to happen and it did. My sister was very wild; she was working for the Cuban embassy in London when the war began. Everybody was leaving London, and she became a warden. Either she was completely mad or she was very courageous, I don’t know.

DB Have you ever been to London?

CH I like London very much, but I’ve never been for any length of time. My sister stayed there. I’d rather be in Europe, but I’m in New York.

DB Why is that?

CH I don’t know. New Yorkers are very strange people. They are the sweetest people on earth, but they can be very strong somehow. But I like New York.

DB So, you came to New York in 1938. Were you painting full-time by then?

CH No, not at all. I had been studying architecture in Havana, but there were too many architects, so they were tough on us: you had to be a genius to pass. Also, I discovered that if you’re an architect you have to deal with the clients. So it wasn’t for me.

DB After World War II, you went to Paris for five years and began exhibiting.

CH In Paris, I was fortunate enough to run into a group of artists called the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles. Non-representation was their answer to the Germans who declared this kind of thinking was degenerate; in little old Cuba, I had been completely oblivious to all of this. Anyhow, I met a lot of people, and I loved it.

DB You exhibited with the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles four times between 1949–52, at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Which other artists were involved in those exhibitions?

CH Everybody. A lot of artists who are very well known today, such as Josef Albers, Jean Arp, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson and Victor Vasarely.

DB You had your first solo exhibition in Havana in 1950 at the Lyceum.

CH Yes, but it was absolutely enough for me. It was very difficult.

DB Were you influenced by your New York peers at that time?

CH I just painted. I knew Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko and met Jackson Pollock, but we didn’t exchange anything.

DB You also became good friends with Barnett Newman.

CH I knew him and his wife, Annalee, very well. When I first arrived in the United States my English wasn’t there at all, and we used to get together; my husband was a good friend of Barnett and I would sit and listen to them. Barnett was a brilliant person. You know, many artists are not brilliant – they love to talk about what they don’t know, so they’re better if they shut up. But not Barnett. As I was learning English, I realized how important he was, how many ideas he had, although he had to pass an examination to get a job as a teacher in a high school, and he couldn’t do it. He was having a crisis when I met him, he wasn’t painting. Annalee said to him: ‘I married a painter. I didn’t marry a schoolteacher.’ And then they managed very well. But, in a strange way, he was different from all the other artists. With them, well, basically it was drink. And having a good time.

DB I read that you were very impressed with Ad Reinhardt’s painting.

CH Yes. But he was a difficult person. Like a lot of artists at that time, he had a thing against Georgia O’Keeffe. But I admired her no end when I first came to America. She was one of my gods. But Reinhardt, he hated her.

DB Why?

CH I don’t know. I can never figure this kind of thing out. I don’t hate anybody too much.

DB And what about the younger generation? Did you meet Donald Judd and the Minimalists?

CH No. I was too old for them; they were too young for me.

DB So, you returned to New York from Paris in 1954 and you’ve stayed here ever since?

CH Yes, my whole life has been here. Cuba is like a memory. A very pleasant memory – until it got unpleasant.

DB And most of your exhibitions have been in New York.

CH I didn’t have that many. The few that I had were here, yes.

DB Many of the group shows that you’ve been in have been exhibitions of Latin American artists.

CH Yes, and I feel terrible about it. I don’t want to be considered a Latin American painter or a woman painter or an old painter. I’m a painter.

DB Is it true that you sold you first work in 2004?

CH No! I sold a little painting here, a little painting there, all the time. Around 1982, I got a telephone call from a man called Rastovski who was opening a gallery on the Lower East Side who said he would like me to show him my work. I said, ‘Do you have a big gallery, because my work is very big?’ And he said, ‘Oh yes.’ My friend Félix González-Torres was showing with him; he had a tremendous eye for artists. But he was not a business person at all and had no backing.

DB You’ve been painting for 80 years. Do you paint every day?

CH Very much so. Especially as I get older. I am more disciplined than I was when I was young.

DB But for nearly 80 years, you’ve painted most days, even when you were undisciplined and young?

CH Yes. When I don’t like the paintings, I say: ‘There’s enough trash in the world, I don’t want them!’

DB Have you any idea how many paintings you’ve made?

CH That I really like? Not too many.

DB When do you decide that the work is no good? Is it immediately after you’ve finished it, or some time later?

CH Sometimes I’m very pleased, sometimes not so pleased, but it takes me a little while to know that a painting is garbage.

DB In my experience, it’s difficult to know if a work is any good until some time later. Beware the work you like!

CH Yes. Although I think I am a good judge; that’s why I throw them in the garbage!

DB On average, how long does it take you to make a painting?

CH It depends on the painting. Sometimes they come very easily, and sometimes you do it, you re-do it, you change it, you throw it away, you take another piece of paper, you do it again. I draw an awful lot before I do anything.

DB Do all of your paintings derive from drawings? Are they very precise?

CH Yes.

DB And then you scale them up onto the painting?

CH Yes.

DB How many drawings do you make compared with paintings?

CH Many, many, many, many.

DB How many will become a painting?

CH That’s a hard one. Sometimes it just requires changing a little bit, and I keep it. At other times, I throw it away.

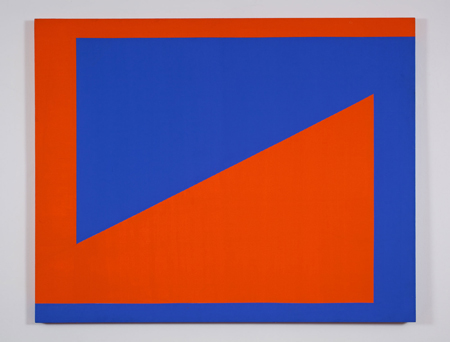

DB From about the mid-1950s, you’ve only made paintings with two colours. Is that correct?

CH Yes. I only use the primary colours anyhow. And I reduce them. Less is more. I didn’t want to say it, but it’s true.

DB Your earlier work, in the 1940s, often only used three colours. And it was more informal, perhaps. Did you make a conscious decision one day to say: ‘ok, that’s it, two colours maximum’?

CH In 1948, I was supposed to bring a painting to Fredo Sidès, who was with the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles. He had a beautiful place in Paris. I went there and I showed him my canvas. ‘Ah’, he said, ‘ah, how beautiful’, and so on and so forth. And then he said ‘Madame, we’re going to show it!’ But then he said: ‘One thing; you have many paintings in this painting.’ And I felt very gratified but as I walked away, I realized what he was saying and said to myself: ‘Oh God, what he’s telling me is that I have too much in it.’ He gave me my first big lesson.

DB So, pretty much since then, you’ve worked with just two colours, flat planes of colour, often with dynamic intersections between the colours. And obviously that’s enough for you.

CH That’s enough.

DB In the last few years, you have done paintings with one colour.

CH A friend of mine said to me: ‘One day you’re going to have just one dot!’ I said: ‘Wonderful. That will be the day!’

DB Have you ever made a single-colour painting with no divisions in it?

CH It would be nice. A blank canvas. That’s it. But I suppose it has been done …

DB You’ve also made diamond-shaped paintings?

CH Yes.

DB What led you to that?

CH I don’t know. It probably comes out of the drawing. When I was young, I stretched all my own canvases with the help of my husband. Then when he died, that stopped.

DB When I think of a diamond painting, it always makes me think of Mondrian. You did a series of paintings called ‘PM’, around 1990. Was this a reference to him?

CH Everybody thought the title had something to do with the weather or the afternoon. PM: Piet Mondrian.

DB So it was an homage to Mondrian?

CH Absolutely.

DB You also work in diptychs.

CH Oh yes. I like them. I don’t know why. It attracts me, the separation, I guess.

DB But also when the canvases are joined together, it’s like another type of division, different from a drawn line.

CH You know, one thing that is very difficult about this type of painting is what goes around it; what do you do? If you frame it, that will kill it. So I think: paint it. That’s what I’ve been doing now for quite a long time, painting on the side of the canvas.

DB I read in the catalogue of your 2009 show at IKON, Birmingham, that colour is the essence of your work. Has that always been the case?

CH Yes!

DB And do you mix your own colours?

CH No. I have a chart. I like Liquitex acrylic paints.

DB Are there certain colours that you find you return to often, ones that work for you?

CH Yellow, cobalt blue and cerulean blue. Cerulean blue and yellow are beautiful. Black and red. Or black and blue, or green. I’m sure the way you paint reflects something that’s happening in your personal life, whether you like it or not.

DB I’ve never seen a painting of yours that has violet or purple in it.

CH No.

DB Why not?

CH It’s not in me. But you’re forgetting that the canvas is a colour too.

DB Can you describe what led you to make three-dimensional works?

CH It’s funny but I don’t know. It’s like if you asked me why I did a black and white painting. I really don’t know. It’s something that I wanted to do. As soon as I had the occasion, which was money, because I’m not a carpenter, I found this guy who was wonderful, and we did it together. But then he wanted to be paid, obviously, and so that ended.

DB When abstract art has straight lines and hard edges, people often talk about it as being systematic and rational and suchlike. But it seems to me a straight line can be as intuitive and improvised as any other kind of line.

CH I love the straight line. I love it. It’s such a nice feeling, too. If some ink falls, I’m devastated.

DB So, your process would be to do a series of drawings until one held your attention? Or something sparks?

CH Yes, yes. I hate to say it, but it’s like a fight. I begin the drawing but the drawing, it’s doing me. And I can get very angry with it. Then sometimes I think I’m doing a new thing, but I have already done it before.

DB The drawing has a kind of logic of its own, that tells you what to do.

CH Yes. I think, in my case, and in that of many people I know, we have a small vocabulary to use. Because it’s not necessary to have more. Less is more. Less is more.

DB You’re a great admirer of the 17th-century Spanish painter, Francisco de Zurbarán. What is it about his work you like?

CH He’s something else. He wasn’t a monk, but he may as well have been one. He painted for all the convents and so on. And I saw his work in Spain, in the proper place, where he had painted for this convent. And it was so beautiful, the whites and the whole table, it was absolutely wonderful. Then there was an exhibition of Zurbarán's work at the Metropolitan Museum, New York, and I went but I didn’t feel anything because it was out of his context.

DB I think all artists love Zurbarán. There’s a work by him in the Prado, Madrid, just four vessels on a shelf. It’s one of the most beautiful paintings I’ve ever seen; there’s nothing in a Zurbarán which doesn’t have to be there. I feel the same about Mondrian, and about Kazimir Malevich, at his best. And I think they’re good company for your work. Can you imagine your work being exhibited alongside Zurbarán?

CH Oh Christ, I would faint. I would simply faint!

DB These days, a lot of young people graduate from college, they’re 24 years old, and they want a big show, and they want to be in a big gallery. What would you say to them?

CH Don’t do it. Don’t even try.

DB Wait for 60 years?

CH I have a friend, a lovely person but she’s just looking for recognition, fame, things like that. And I don’t know how to tell her, that’s not the whole thing.

DB But now you’re well known, you’re recognized. Does it matter to you? Did it matter to you when people really didn’t know your work very well? Was that ok?

CH Not really. I wished it was different, but what can you do?

DB What can you do? You can continue, that is all you can do, I guess.

CH Because you can’t stop. And that’s my case. Fine, who doesn’t want to be recognized, to make money, to be in the paper, all that? Oh, terrific! But that’s not it. And that’s what I try to tell them, and they don’t understand what you’re talking about. Whenever I finish a work that I’m happy with, I think: ‘Great!’ But that’s rare.

DB And when you finish a work that you’re not happy with? How does that feel? Flat?

CH Yes. But then you look at it again, and it’s not as bad as you think it was. Or you throw it in the garbage, if somebody lets you.

DB How do you feel about these black and white drawings that you are working on now?

CH I think I have to make six more and, after that, I’ll go back to colour. I’m dying to go back to colour. Maybe I should just stop and go back to colour, who knows?

DB Would you say you are content?

CH Oh yes, I am. I am.

Born in Havana, Cuba, in May 1915, Carmen Herrera has been living and working in New York, USA, since 1954. In recent years she has been the subject of solo exhibitions at Lisson Gallery, London, UK (2012); Museum Pfalzgalerie, Kaiserslautern, Germany (2010); Frederico Sève Gallery, New York (2010); and IKON, Birmingham, UK (2009). In 2013, her work will be included in the group show ‘Order, Chaos and the Space Between’ at the Phoenix Museum of Art, USA, and a solo exhibition of new work opens at Lisson Gallery, Milan, Italy, on 25 January.