Surfacing

Monika Baer talks about her approach to painting’s surfaces, which teeter between anti-illusionism and illusionism, tactile and optical qualities, real holes and key holes

Monika Baer talks about her approach to painting’s surfaces, which teeter between anti-illusionism and illusionism, tactile and optical qualities, real holes and key holes

MARK PRINCE In your work, there’s a sense of not being able to get beyond the surface of a painting. Your recent paintings are characterized by signs of blocked entry: keyholes, chains, brick walls, spider webs or road markings that function as barriers. They’re illusions at the same time as being critiques of painterly illusion.

MONIKA BAER I think you’ve summed up my motifs merely on the narrative level. I don’t accept the surface of the painting as something taken for granted. On the one hand, the spider’s web paintings are these little monochrome canvases that have been cut into using a photo of an individual web as a Vorlage [template] so they represent an actual spider’s web. On the other hand, the surface has been opened up so you can see the wall and the support. It’s an anti-illusionistic move. The monochrome and the incision suggest the object while the strands of canvas and the gaps between them stand for the spider’s web, which is illusionistic. So it’s both at the same time.

In those pieces you dramatize a pivoting between access and limitation.

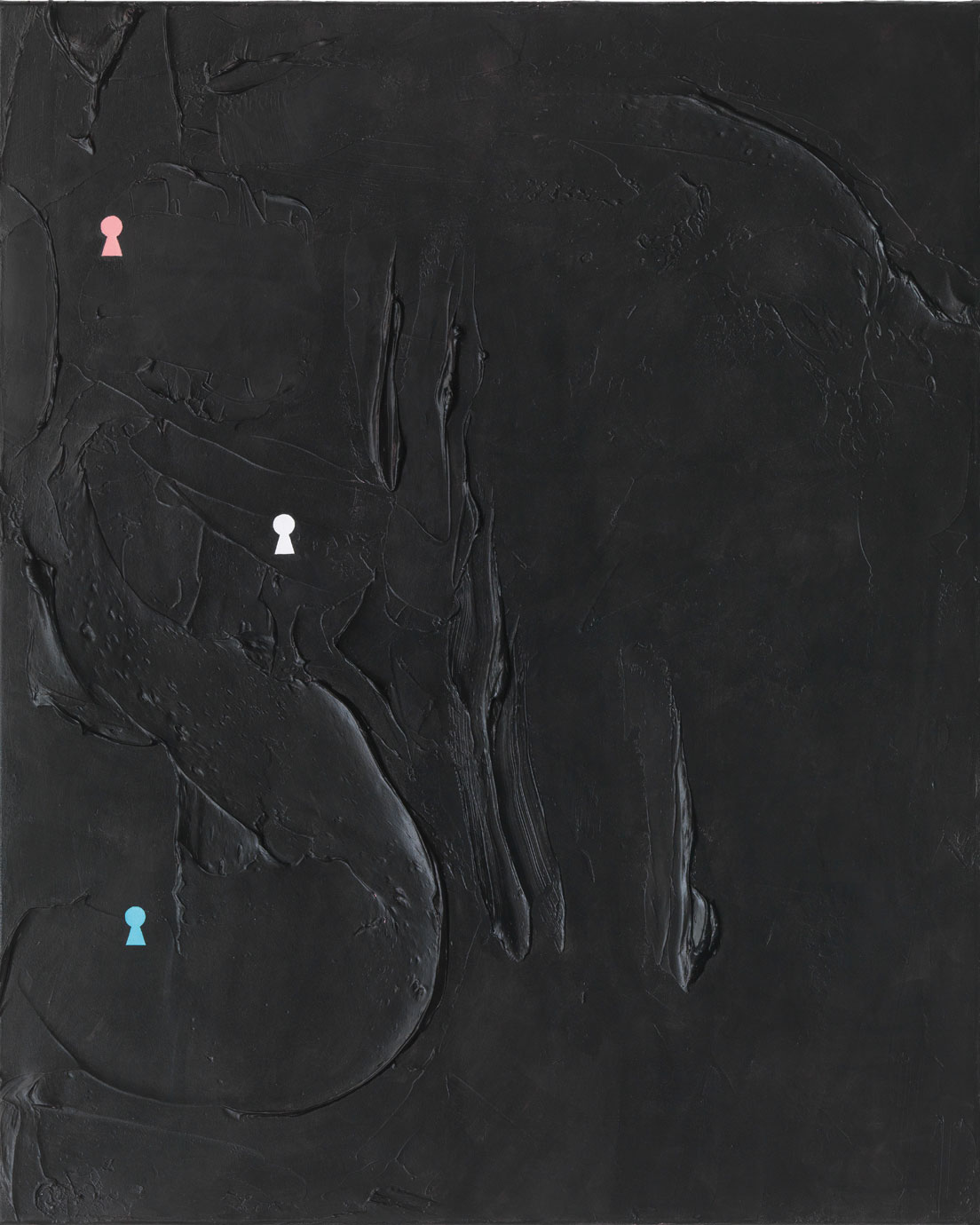

MB Yes, and between illusion, effect and object as well as between front and back. The same applies to the new pink paintings with the keyholes. They are posing as monochromes, as abstract paintings displaying pastose brushwork. The little keyhole switches them from the monochrome – I wouldn’t necessarily say to a surrealistic object – but to something that implies its other side, which removes the painting from being categorized as minimalist. So there again, it is going to and fro.

This to-ing and fro-ing seems to have a moral dimension. David Foster Wallace said he thought that writers are more afraid of appearing sentimental than twisted or corrupt, because sentiment has become so associated with its misuse by, among others, corporate entertainment devices to manipulate us. Would illusionism be the equivalent in painting?

MB I think it depends on how and why this means is employed, and if this is then articulated within the illusionistic set-up. I’d say that scepticism is the basis of my approach to painting. An example of the use of illusionism in my work are the Vampire Paintings (2007) that were shown at documenta 12. When I use illusionism in this way, it is in keeping with the logic of theatre scenery. As if I were a theatre director staging material, using lighting and shadows – papier mâché props with the pretence of gravity and backdrops. It is a device that is employed while being displayed as well.

Contemporary art is rife with cultural references and references to other art works, but the theatrical motifs you manipulate are not so much references as self-referential counters that become associated with the world of your work.

MB Rather than being references to other work, the motifs are commonplace signifiers that are manipulated, as you say, or moulded to activate their specific function within the painting or the series. When they turn up again in a new series of paintings or with a new function, they may appear as a kind of marking and create echoes with former works.

Does this lack of referentiality imply being sealed within the solipsistic world of a painting?

MB On the contrary. It seems that a vocabulary is being constructed while I am moving along. It changes, is modified, extended, et cetera as I try to articulate what is at hand. The motif elements are commonplace, sometimes aggressively so, and are employed among other things to establish a place of contact. Because this is a system which is reactive and in motion, it is permeable. Anyway, I wonder from whose point of view the world of a painting – or of painting itself – is solipsistic? Do you expect to read a painting as you could a facial expression? The question is whether the work generates a kind of agency and if its articulation is putting itself out for discussion in addition to that.

We’ve talked about the symbolic limitation of illusionistic space, but there’s another kind of narrative space suggested by the continuous relation between the individual paintings, and also between groups of paintings: the elaboration of your own iconography.

MB Yes, there’s the actual space of the paintings; but the other thing, as you say, is the space that develops from the correspondences between works and series, which grows over the years into a certain space that I have in mind, of which the paintings are only the visible part. For instance, I observe that what I thought of as ruptures occur with regularity, creating a rhythm. These rhythms seem to build up to something like an invisible architecture. And one new painting can supply the information for entering into a new series but also to alter the imaginary positioning of a former group.

There is continuity, but also a sense of clashing registers – of different languages coexisting within the same painting. You studied at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, in the 1980s, when Gerhard Richter was teaching there. You once said there was a sense that painting was simply no longer possible. But Richter, in simultaneously presenting heterogeneous positions within his oeuvre, would show that even if it seemed impossible to go on painting, one could still go on. Are you presenting on a single canvas the heterogeneity which he kept apart, in separate categories of painting?

MB The way that scepticism combined with the ongoing struggle for a possibility is thematized in Gerhard Richter’s work provided a base for me, although this has actually become apparent only recently as I was very interested in his conceptual approach with its distance to painting, although I was less into his actual work. And again, this principal questioning of painting’s capacity to be of any relevance, which is at the base of my work and provides a powerful motive to work at all, stems from having studied in Germany in the eighties. The fractures, conflicts and contradictions are active in a single painting as well as in the relations between my paintings, but they are all incorporated into an encompassing questioning …

The motifs you use return us to thinking about how a painting is made. It’s not only a question of trying to find a way to go on, but of finding a way to reflect on how to go on. For example, there is the cash motif – the coins and the euro bills – which you place against washy, nebulous backgrounds. They make us think about how paintings are manipulated.

MB Are you asking me what the cash means symbolically?

Paintings are traditionally thought of as being the art objects most likely to be manipulated by the market; to be the most functional, in market terms. And many painters are looking for strategies to pre-empt the market.

MB I don’t know if it is the paintings that are the most functional in market terms. Until now I haven’t had the problem of earning too much money or being alienated from my work by the manipulations of the market, but that may be because I am quite conscious of whom I work with. A small painting shown at documenta 12, a work that I love, ten dollars in a state of disintegration (2007), has not been sold. Maybe because of the title.

Are you trying to pre-empt the market?

MB Not really. First of all, the theme of the money bills came out of the motif of the coins, which themselves were derived from slices of sausages – that’s where they are from. Money, sausage slices, faces, road markings, breasts, are all painted onto a basic form, a rectangle, circle or oval that has been stencilled, primed white and sanded. The motif is laid onto this carrier, like a layer or a mask.

But why money?

MB The motif opens a region of potential discussion around it, rather than illustrating a position. The topic of money is inserted into the paintings themselves instead of them being immersed in the market in the guise of a commodity. It is a pun on the short cut painting money, and of course I think of value and prices – the paintings demonstrate the generation of monetary value. I don’t supply interpretations on a symbolic level, but I can describe the connections that these symbols – if we call them such – have with others. The connection between money and meat or flesh for example, or money as bounty or the way, in hunts, the body of the prey is opened, and the sight of the entrails stands for the final possession of the animal. The access of the viewer’s gaze to the exposed insides marks his or her position of domination. I was wondering if money, consisting entirely of exposed, intricate outsides, signifies and establishes this relationship. So it depends on the placement of the motif, how that radiates from the material. It is while I’m moving towards the motif and honing it down, that I am wondering what I am doing.

So you come upon the motifs intuitively?

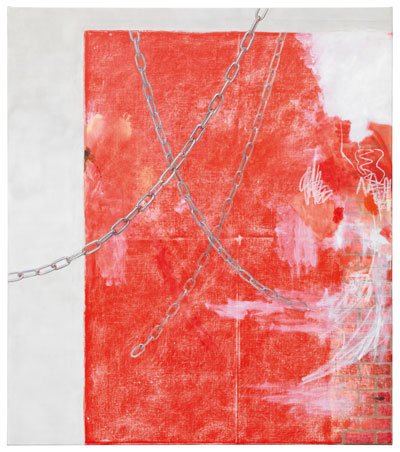

MB Yes – a chain is not used to illustrate one certain intention. The motifs are not employed in such a functional way. I have another relation to them. But I must say, after painting chains and brick walls for months, I did get the impression of constructing a prison mainly for the joy of breaking out …

But when one sees these motifs in juxtaposition within a series of works, they suggest a critique of painting’s fundamental premises – its ability to realize perceptual space and its commodity value. Applying a critique to a sensuous process is a Conceptual art inheritance. You spoke about first becoming aware of US Conceptualism in Dusseldorf and Cologne when you were starting out.

MB Yes, when I started studying in Dusseldorf I was introduced to conceptual and performance art of the sixties and seventies – this was a revelation. I loved Baldassari’s text paintings. I thought, conceptual art is actually what art is.

As distinct from painting?

MB I was interested in somehow pulling it through with painting. It wasn’t only that I wanted to paint, it was that I was asking how can you paint and make it be art? That’s basically the question, and still is. Painting was not automatically art for me.

If it wasn’t art, what was it?

MB In the uninteresting version: a practice that doesn’t have to expose itself to questions art can pose because it relies on functioning within its own realm and its own logic. A position that relies on the parameters that have been developed, and stays within them. Instead of using them.

Conceptual art is structuralist, but also empirical. It goes back to basic observation. It gets out of the gallery and attempts to look at the world as it actually is. Your work is certainly structural and self-reflexive, but it doesn’t seem empirical. There is a desperate juggling and reordering of motifs which point inwards.

MB ‘Desperate juggling’ is not so bad, but it certainly is not occurring in a hermetic space. I don‘t think the paintings are pointing inwards. In fact I am very conscious about them facing inward and outward at the same time. The reason the constellations within the paintings and between the paintings seem to me to be in a process of ongoing transformation is that they are reacting to my experience of the world.

I mean desperate as in a Lars von Trier movie, in which he’s showing that the form he is using is used up, but he’s nevertheless going on with it.

MB This is the contradiction I find so fruitful because it generates an urgency. It’s great if painting, or film or photography is used up! It opens up a lot of possibilities that lie in the assumed impossibility, and this conflict makes simple solutions and assertions with their homogeneous surfaces and treatments less obvious. I’m not intimidated anymore by the critique that painting can’t be relevant. I think it can function on a comparable level to reading a theoretical and poetic text. When you’re looking at a painting, you’re not trying to recognize it like you would a sign. You’re asked to expose yourself to the painting, which is exposing itself back. This contact is a complex process.

Exposure suggests a submission to the medium. Painting is a medium that is notoriously unpredictable in its handling. But it seems as though you are always very much in control of the effects you want to create. You don’t seem to be working with accident.

MB Hardly. Well, in Extended Failure (2011–12), one of the three red chain paintings shown at my recent show Return of the Rear with Barbara Weiss in Berlin, you could say I was working with accidental features. This was a failed painting which was brought to the restorer, who added on pieces of canvas because I thought that enlarging the format might provide a means to save it. So what I have now is a new painting incorporating a failed painting. The canvas extensions are painted greyish, and I’ve painted two chains over the whole format, connecting both parts.

You spoke earlier about motifs emerging intuitively, although the process always seems to be extremely controlled.

MB For instance, I wanted to paint red paintings including one or more swinging chains. At the beginning I don’t know what they mean, I ward off analysis and let them develop. I just follow through. The paintings and their motifs are not directly illustrating an intention. I stay with the motifs and concentrate on where they are taking me and their placement, and I allow myself to go anywhere, whether I like it or not. My paintings don’t have to conform to my taste. This can bring me to difficult places, as in the Vampire paintings or the paintings incorporating girls’ faces, flowing hair and skulls Steindamm (2005). These are paintings I refer to as theatrical, and here I employ the illusionism we have talked about to create a scene. They can give me a hard time as I commit to the exaltation and pathos that inhabits them, which brings me into a risky proximity to sentimentality, which I am definitely trying to stay clear of. I find this complicated work. The specific treatment of the motifs and their different constellations with the other elements has to be found out for each painting.

You seem to allow the recent paintings to be emptier and more mute, to manage with fewer nameable elements. Is that because you feel able to draw on the existing cultural profile of the work: you can make a monochrome painting and the context will somehow fill in the gaps?

MB But they all have at least one significant little keyhole, without which they wouldn’t work, because the keyhole tips the painting out of a reliance on certain categories of painterliness. For me, those paintings build up an assumption which gets contradicted by the keyhole – an everyday, commonplace symbol which of course also has surrealist connotations. And I think of surrealism as a form of antidote to the minimalism of the monochrome’s materiality. Without the keyhole, the painting falls back on a more traditional strain; with it, the work is slapped back to the lowly level of Catholic guilt – secrecy, voyeurism, etcetera – as well as suggesting that it is a front.

The keyhole is also a window, in a way – something that could be a vehicle for illicit viewing, for transgression.

MB It’s like a symbol from the cover of a cheap mystery novel, counteracting associations of the elegance of Fontana and Manzoni. The black painting with a pink keyhole – return of the rear (2011) – was suggested by Fontana’s work. I was thinking about the space created when he cut the canvas, and then placed a black cloth behind it, like a vaudeville set, a travelling theatre or a backdrop that claims: ‘This is open to the universe.’ But it’s merely a little black cloth. I was rubbing my hands and thinking, ‘I wonder what such a painting would look like from the back.’ You would see a frame and the canvas and a pathetic bit of cloth stuck to it. I assume this has to do with the Other, the male/female binary. For Fontana, it would be the slit and the world that opens up beyond. So I imagine myself grimly staring back and turning this grand slit into a little anal keyhole.

Monika Baer lives and works in Berlin.