Women in the Well: When Joan Jonas Met Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill

While the American artist was staying in Dublin in the 1990s, she encountered a female character with a wildness to match Mad Sweeney

While the American artist was staying in Dublin in the 1990s, she encountered a female character with a wildness to match Mad Sweeney

Among the aspirations of the long-awaited Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA), which eventually opened in 1991, was the fostering of exchanges across both cultural and disciplinary borders. Some particularly fruitful transactions were facilitated between the visual and verbal arts. The year before IMMA opened, one of the most celebrated writers in the Irish language, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, had her breakthrough to an international readership with Pharaoh’s Daughter (1990), which featured English translations of 45 of her Gaelic poems by such distinguished writers as Seamus Heaney, Michael Longley and Paul Muldoon. Over the previous two decades, Ní Dhomhnaill had produced a unique body of poetry informed by the advent of feminism, a minute attention to the flora and fauna of the southwestern Irish seaboard and a fascination with Jungian archetypes – especially as reflected in early Irish literature and traditional folk narrative.

Not long after the publication of Pharaoh’s Daughter, the American performance and video artist Joan Jonas spent several months in Dublin while preparing for her first European retrospective at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, ‘Works 1968–1994: A Retrospective’. This period marked the career-changing transformation of her performance pieces into full-scale installations. As she later recalled: ‘It had a major effect on me. I became interested in what an installation could be.’ For that show, she made Revolted by the Thought of Known Places ... Sweeney Astray (1992–94), a complex installation based on Heaney’s translation of the 12th-century Gaelic tale of Suibhne Geilt (Mad Sweeney).

Sweeney was an arrogant king cursed by Saint Ronan to a life of demented wandering in the wild, naked and feral, his only consolation a penchant for exquisite nature poetry. An Irish exemplar of the mythical figure of the ‘wildman of the woods’, who appears in medieval European art and literature, Sweeney – whose tragic tale had previously drawn the attention of writers such as T.S. Eliot and Flann O’Brien – meets with a violent death. For Jonas, Revolted by the Thought of Known Places ... Sweeney Astray expanded an interest in epic narrative heralded some years earlier by Volcano Saga (1985–89), which she based on the 13th-century Icelandic Laxdaela Saga. Jonas would later incorporate into another major installation, Lines in the Sand (2002), the famous ‘Pillow Talk’ episode, featuring a squabbling king and queen, adapted from the most revered text in Gaelic literature, Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Táin), a medieval epic poem sometimes referred to as ‘the Irish Iliad’.

Jonas's stay in Dublin also brought her into productive contact with Ní Dhomhnaill, resulting in another, less well-known installation, a companion piece to the Sweeney-inspired work. Far less well-known than any of the narratives mentioned so far is the romance of Mis and Dubh Ruis. During her time in Dublin, Jonas was consciously searching for a female character from the medieval Irish tradition with a resonance to match that of Sweeney. As luck would have it, Ní Dhomhnaill had just published a speculative essay titled ‘Mis and Dubh Ruis: A Parable of Psychic Transformation’. Introductions were made and the poet supplied the artist with a copy of her English translation of the tale. Echoing elements of Suibhne Geilt, Mis loses her mind following the death of her chieftain father in battle, becoming a fearsome wild creature who lays waste to the lands around her and kills all warriors sent to subdue her. It eventually falls to the king’s harper, Dubh Ruis, to coax Mis back from the wild by means of a variety of cautious enticements, including a scene of sexual congress notable for the vulnerability of the male protagonist. Though essentially a version of the sovereignty myth of the puella senilis, in which an old crone is transformed into a beautiful maid by being united with her rightful mate, the story of Mis particularly appealed to Jonas due to its blend of humour and eroticism.

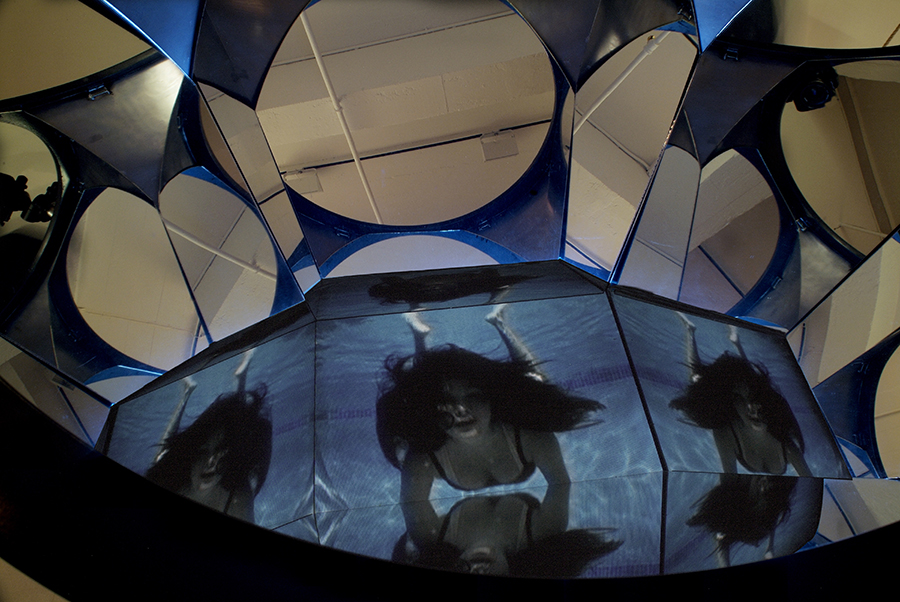

In keeping with the magpie proclivities that have consistently enriched Jonas’s work, Ní Dhomhnaill’s poem was adapted into a soundtrack for Woman in the Well (1996/2000), an installation whose main component is a replica of a traditional wishing well. At the bottom, a monitor shows footage of a woman performing several actions under water, while repeatedly returning the viewer’s gaze. Text and image are deliberately disjunctive and reflect, as Jonas puts it: ‘A process in which a story from one source or culture comes into contact with another and is caught, separated from origin and altered.’ While Jonas’s work is unlikely to have been influenced by Ní Dhomhnaill’s early poem An Bhábóg Bhriste (The Broken Doll, 1990, translated by John Montague ) – a potent brew of mythic motif and naturalistic detail in which a child wandering on a hillside, startled by an unfamiliar sound, accidentally drops his doll into a well – the text nonetheless confirms how well met the Irish poet and American artist were. Like Woman in the Well, An Bhábóg Bhriste concludes with a returned female gaze from below, in this case an image most likely indebted to a famous pre-Raphaelite painting:

[...] you see the vixen and her brood

stealing up to lap the ferny swamphole

near their den, the badger loping to wash

his paws, snuff water with his snout. On

Pattern days people parade seven clockwise

rounds; at every turn throwing in a stone.

Those small stones rain down on you.

The nuts from the hazel tree that grows

to the right of the well also drop down;

you will grow wiser than any blessed trout

in this ooze! The redbreasted robin

of the Sullivans will come to transform

the surface to honey with her quick tail,

churn the depths to blood, but you don’t move.

Bemired, your neck strangled with lobelias,

I see your pallor staring starkly back at me

from every swimming hole, from every pool, Ophelia.

Main image: Joan Jonas, Woman in the Well, 1996, video installation. Courtesy: the artist and Gavin Brown's enterprise, New York