‘A comic strip of Life, printed on Semtex’*: the films of Jeff Keen

Magazines and newspapers in late December and early January are awash with ‘best of…’ roll-calls of the past 12 months and forecasts for next dozen, and the current January–February issue of frieze is no exception. But before 2010 unfolds too far, there’s one item I really feel deserves mention as one of the real highlights of 2009: the DVD box-set released last year by the British Film Institute entitled Gazwrx: The Films of Jeff Keen.

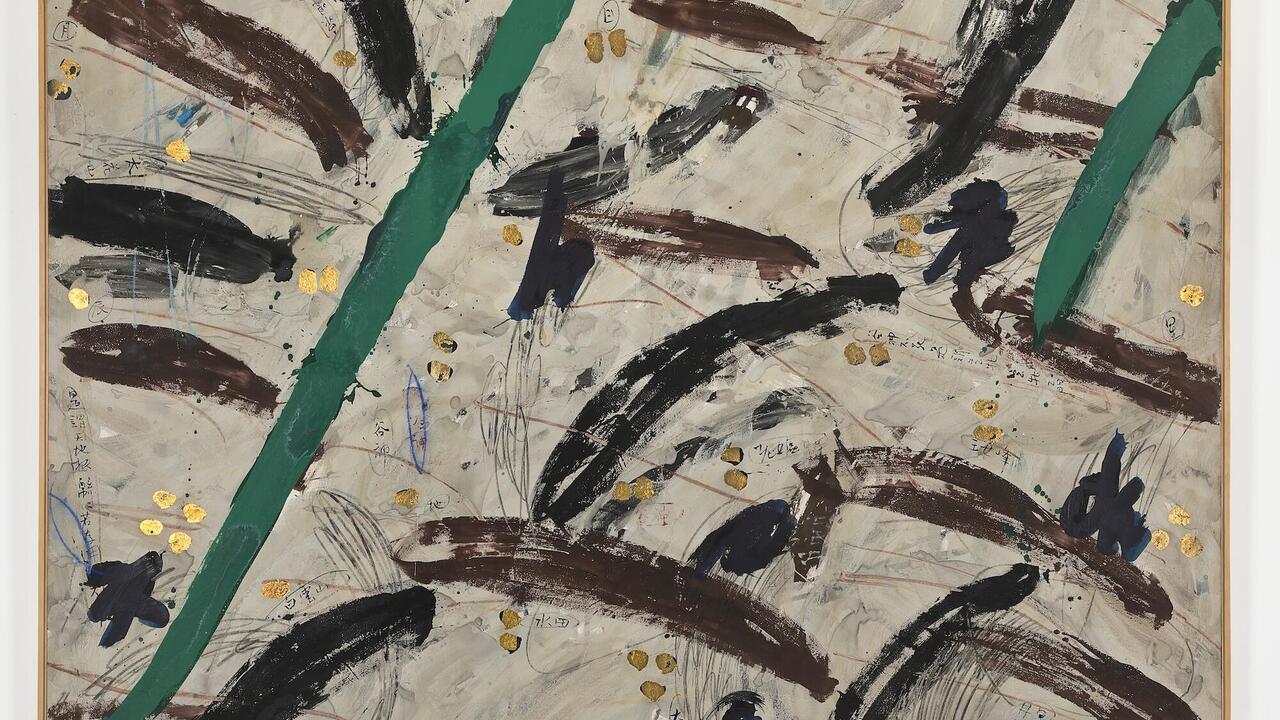

Gazwrx surveys the 50-year – that’s right, 50-year – career of British artist and filmmaker Jeff Keen, and is essential viewing for anyone with even a passing interest in the history of experimental film and video. Keen’s films – from his first 8mm work Wail, made in 1960, to recent films such as Joy Thru Film (c. 2000) and Omozap Terribelis + Afterblatz 2 (2002) – are high-voltage visual shocks, eruptions of pulp imagery, eroticism, violence, language games, uncensored imagination and sheer giddy exuberance. His early films are love-letters to cinema history: to silent film and B-movies, to slapstick, thrillers, exploitation flicks and sci-fi apocalypses, his later works disquieting parades of video news imagery and documentation of his own creative processes. Frankenstein and Godzilla share the screen with Keen’s own cast of heroes and villains such Motler the Word Killer, Dr Gaz, Silverhead, Omozap and Mothman (often played by friends and family). Edited into machine-gun sprays of imagery, Keen’s pedal-to-the-metal, high-speed films are like animated collages – action painting with the stress very much on action. (‘If words fail use your teeth’, as an inter-title in one of his films declares.) In an interview from 1983 included on Gazwrx …, Keen argues how his fast cutting technique emphasizes the brutal way in which film works – the claw of the projector dragging the film through the gate, 24 frames per second, rapidly devouring and spewing images – although, as he also wryly puts it, ‘speed is relative, you know?’

Keen was born in 1923, in Trowbridge, Wiltshire. He spent World War II working on experimental bombers and tanks; an experience which was must have been an influence on later works such as Day of the Arcane Light (1969) and the various iterations of his Artwar film throughout the 1990s, which feature images of warplanes, or civilian aircraft taken from the found footage or at airshows. After leaving the army, Keen moved first to London, where he encountered abstract and Surrealist art, and then to Brighton where he met and married Jackie Foulds, who features in many of Keen’s films from the 1960s and ‘70s. He was aged almost 40 when he made his debut, Wail, partly as a way of helping maintain a college film society which he was involved in running. In the early ‘60s his films found their way onto the UK’s small amateur film circuit, and later gained more exposure on the nascent underground film circuit of the late ‘60s, at venues such as Better Books in London (a hub for the city’s counterculture scene) and with both the BFI and the London Film-Maker’s Co-Op. Throughout the 1970s, ‘80s and into the ‘90s, Keen found support for his work from both art contexts (including the 1977 Hayward Gallery exhibition ‘Perspectives on Avant-Garde Film’) and British television, during the early days of Channel Four, when it had a commitment to more radical forms of broadcasting, rather than the trashy makeover shows and miserable reality-TV it peddles today. Early in 2009, Permanent Gallery in Brighton held ‘GAZWRX & RAYDAY’, an exhibition of works by Keen and Ian Helliwell, marking the launch not only of the BFI DVD set, but also a boxed edition of Keen’s lively broadsheet publication Rayday, produced by Permanent Gallery.

With their blunderbuss shots of plastic toys, comic strips, advertisements and pin-ups, a number of Keen’s films from the 1960s – such as Cineblatz (1967), White Lite (1968) and Marvo Movie (1967) – might be said to share certain formal similarities with British Pop Art, in particular the work of Eduardo Paolozzi, yet Keen never considered himself a Pop artist in the sense that it is understood today as a historical movement. For Keen, popular culture is just part of the contemporary landscape, there for the taking, and he admits to a nostalgia and preference for the handmade (though I’ve often thought that the handmade is a characteristic peculiar to 1950s and ‘60s British Pop – dowdy austerity Britain, dreaming of America’s glass, chrome and plastic visions of the future.). And it’s in the handmade, homespun quality of Keen’s films that much of their power resides. Though much of his work is made on 8mm and 16mm film – the filmstrips often scratched into, bleached or painted over, giving them a distinct sense of physicality, and often involving multiple projection – the handmade quality is evident even as Keen moves forward with technology: a good example being Omozap Terribelis + Afterblatz 2, which features animated, computer generated drawings made with a My First Sony toy. Also striking is the sense of community one gets from these works: friends and family all happily taking part, whether playing roles or just appearing in the many diary films from which Keen also sources much of his imagery. Mad Love (1972–8), for instance, is an affectionate homage to silent film and film history, constructed from still shots and tableaus featuring relatives or fellow artists and writers acting out scenes fondly spoofing or imitating movie genres; in Keen’s words, friends ‘playing at being stars’.

In this regard, Keen is a fellow traveller of US experimental filmmakers such as Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith and Andy Warhol: his films convey a strong ‘can do’ attitude and sense of creative self-sufficiency and artistic self-empowerment. This could also be described as a punk sensibility, and some of his work – especially where they seem to evoke a kind of Cold War fear of impending apocalypse, as in the desolate landscape depicted in Day of the Arcane Light, for instance, or the violence of Artwar – seem to have a distinctly post-punk quality to them. In addition to its avant-garde aspects, Wail, for instance, predates Bruce Connor’s use of B-movie and medical imagery in his video for Devo’s Mongoloid (1978) by nearly 20 years, and many of the imagery used in the films suggests similar rock’n’roll, horror film and comic book reference points to Off the Bone-era Cramps or The Very Things’ The Bushes Scream While My Daddy Prunes. The eerie soundtracks to Marvo Movie (which also features the voice of the brilliant poet Bob Cobbing) or Instant Cinema (1964–5/2007) could even be straight off an early 1980s record by Throbbing Gristle or Cabaret Voltaire.

Gazwrx is a rich compendium of Keen’s work: it features four DVDs, and a highly informative booklet that, along with notes to the work and a biographical essay by the box-set’s producer, William Fowler, also includes a selection of the artist’s striking posters and drawings, which visually shout and scream with the energy and anger of a Jean Dubuffet or John Heartfield. Hopefully, with the release of Gazwrx, his work will now find wider audiences and in this new decade bring Keen – now 85 – the recognition he deserves as a pioneer of avant-garde film.

- Title taken from a short epigraph by Jeff Keen published in the booklet for Gazwrx: The Films of Jeff Keen

Jeff Keen’s website can be found at kinoblatz.com

Dan Fox is based in New York, USA, and is senior editor of frieze

Magazines and newspapers in late December and early January are awash with ‘best of…’ roll-calls of the past 12 months and forecasts for next dozen, and the current January–February issue of frieze is no exception. But before 2010 unfolds too far, there’s one item I really feel deserves mention as one of the real highlights of 2009: the DVD box-set released last year by the British Film Institute entitled Gazwrx: The Films of Jeff Keen.

Gazwrx surveys the 50-year – that’s right, 50-year – career of British artist and filmmaker Jeff Keen, and is essential viewing for anyone with even a passing interest in the history of experimental film and video. Keen’s films – from his first 8mm work Wail, made in 1960, to recent films such as Joy Thru Film (c. 2000) and Omozap Terribelis + Afterblatz 2 (2002) – are high-voltage visual shocks, eruptions of pulp imagery, eroticism, violence, language games, uncensored imagination and sheer giddy exuberance. His early films are love-letters to cinema history: to silent film and B-movies, to slapstick, thrillers, exploitation flicks and sci-fi apocalypses, his later works disquieting parades of video news imagery and documentation of his own creative processes. Frankenstein and Godzilla share the screen with Keen’s own cast of heroes and villains such Motler the Word Killer, Dr Gaz, Silverhead, Omozap and Mothman (often played by friends and family). Edited into machine-gun sprays of imagery, Keen’s pedal-to-the-metal, high-speed films are like animated collages – action painting with the stress very much on action. (‘If words fail use your teeth’, as an inter-title in one of his films declares.) In an interview from 1983 included on Gazwrx …, Keen argues how his fast cutting technique emphasizes the brutal way in which film works – the claw of the projector dragging the film through the gate, 24 frames per second, rapidly devouring and spewing images – although, as he also wryly puts it, ‘speed is relative, you know?’

Keen was born in 1923, in Trowbridge, Wiltshire. He spent World War II working on experimental bombers and tanks; an experience which was must have been an influence on later works such as Day of the Arcane Light (1969) and the various iterations of his Artwar film throughout the 1990s, which feature images of warplanes, or civilian aircraft taken from the found footage or at airshows. After leaving the army, Keen moved first to London, where he encountered abstract and Surrealist art, and then to Brighton where he met and married Jackie Foulds, who features in many of Keen’s films from the 1960s and ‘70s. He was aged almost 40 when he made his debut, Wail, partly as a way of helping maintain a college film society which he was involved in running. In the early ‘60s his films found their way onto the UK’s small amateur film circuit, and later gained more exposure on the nascent underground film circuit of the late ‘60s, at venues such as Better Books in London (a hub for the city’s counterculture scene) and with both the BFI and the London Film-Maker’s Co-Op. Throughout the 1970s, ‘80s and into the ‘90s, Keen found support for his work from both art contexts (including the 1977 Hayward Gallery exhibition ‘Perspectives on Avant-Garde Film’) and British television, during the early days of Channel Four, when it had a commitment to more radical forms of broadcasting, rather than the trashy makeover shows and miserable reality-TV it peddles today. Early in 2009, Permanent Gallery in Brighton held ‘GAZWRX & RAYDAY’, an exhibition of works by Keen and Ian Helliwell, marking the launch not only of the BFI DVD set, but also a boxed edition of Keen’s lively broadsheet publication Rayday, produced by Permanent Gallery.

With their blunderbuss shots of plastic toys, comic strips, advertisements and pin-ups, a number of Keen’s films from the 1960s – such as Cineblatz (1967), White Lite (1968) and Marvo Movie (1967) – might be said to share certain formal similarities with British Pop Art, in particular the work of Eduardo Paolozzi, yet Keen never considered himself a Pop artist in the sense that it is understood today as a historical movement. For Keen, popular culture is just part of the contemporary landscape, there for the taking, and he admits to a nostalgia and preference for the handmade (though I’ve often thought that the handmade is a characteristic peculiar to 1950s and ‘60s British Pop – dowdy austerity Britain, dreaming of America’s glass, chrome and plastic visions of the future.). And it’s in the handmade, homespun quality of Keen’s films that much of their power resides. Though much of his work is made on 8mm and 16mm film – the filmstrips often scratched into, bleached or painted over, giving them a distinct sense of physicality, and often involving multiple projection – the handmade quality is evident even as Keen moves forward with technology: a good example being Omozap Terribelis + Afterblatz 2, which features animated, computer generated drawings made with a My First Sony toy. Also striking is the sense of community one gets from these works: friends and family all happily taking part, whether playing roles or just appearing in the many diary films from which Keen also sources much of his imagery. Mad Love (1972–8), for instance, is an affectionate homage to silent film and film history, constructed from still shots and tableaus featuring relatives or fellow artists and writers acting out scenes fondly spoofing or imitating movie genres; in Keen’s words, friends ‘playing at being stars’.

In this regard, Keen is a fellow traveller of US experimental filmmakers such as Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith and Andy Warhol: his films convey a strong ‘can do’ attitude and sense of creative self-sufficiency and artistic self-empowerment. This could also be described as a punk sensibility, and some of his work – especially where they seem to evoke a kind of Cold War fear of impending apocalypse, as in the desolate landscape depicted in Day of the Arcane Light, for instance, or the violence of Artwar – seem to have a distinctly post-punk quality to them. In addition to its avant-garde aspects, Wail, for instance, predates Bruce Connor’s use of B-movie and medical imagery in his video for Devo’s Mongoloid (1978) by nearly 20 years, and many of the imagery used in the films suggests similar rock’n’roll, horror film and comic book reference points to Off the Bone-era Cramps or The Very Things’ The Bushes Scream While My Daddy Prunes. The eerie soundtracks to Marvo Movie (which also features the voice of the brilliant poet Bob Cobbing) or Instant Cinema (1964–5/2007) could even be straight off an early 1980s record by Throbbing Gristle or Cabaret Voltaire.

Gazwrx is a rich compendium of Keen’s work: it features four DVDs, and a highly informative booklet that, along with notes to the work and a biographical essay by the box-set’s producer, William Fowler, also includes a selection of the artist’s striking posters and drawings, which visually shout and scream with the energy and anger of a Jean Dubuffet or John Heartfield. Hopefully, with the release of Gazwrx, his work will now find wider audiences and in this new decade bring Keen – now 85 – the recognition he deserves as a pioneer of avant-garde film.

- Title taken from a short epigraph by Jeff Keen published in the booklet for Gazwrx: The Films of Jeff Keen

Jeff Keen’s website can be found at kinoblatz.com

Dan Fox is based in New York, USA, and is senior editor of frieze