Ade Darmawan’s Installations Distil Thorny Histories

At Cemeti – Institute for Art and Society and ROH Projects, the artist’s exploration of extraction in Indonesia asks: ‘How to reverse the tide?’

At Cemeti – Institute for Art and Society and ROH Projects, the artist’s exploration of extraction in Indonesia asks: ‘How to reverse the tide?’

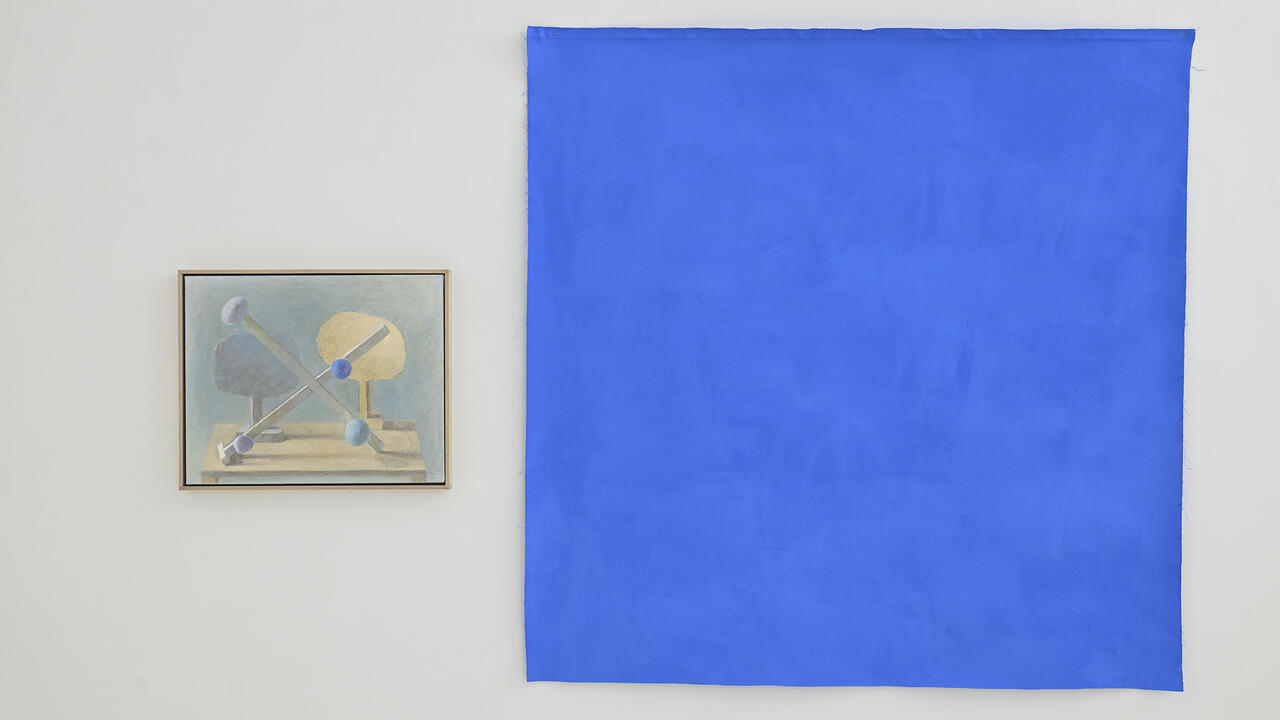

‘Water Resistance’ is Ade Darmawan’s first show in Indonesia in 12 years. Spanning Cemeti – Institute for Art and Society in Yogyakarta and ROH Projects in Jakarta, where Darmawan is based, the two-venue exhibition spotlights an artist perhaps best known as a member of the collective ruangrupa (est. 2000). In one corner of Cemeti – where, as a young graduate, he staged his first-ever solo presentation in 1997 – are five repurposed oil drums heated by gas burners (Konsentrasi Formal Per Barrel, 2024). Organic materials, including nutmeg, cloves and jasmine, transform as they travel from the tanks through jerry-rigged exhaust pipes and glass condensers, eventually oozing into jars in the form of dark, aromatic distillates. Studying the rigs, I started to sweat.

Darmawan chose these materials because they appear in Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s 1995 book Arus Balik, which can be translated as ‘turning of the tide’. Drafted in the 1970s while the author was imprisoned on Buru Island, in Maluku, for his ties to the communist-affiliated Institute for People’s Culture, the epic novel narrates the 16th-century breakup of the Majapahit empire, a maritime kingdom that covered much of present-day Indonesia. Pramoedya’s novel, and this exhibition in turn, contemplates the historical shift from a sea- to land-based economy in the archipelago.

On an island of white desks, Tuban (2019) – titled after the Javanese port where Arus Balik takes place – features further distillation apparatuses, which trickle essential oils onto biographies of Indonesia’s cronyistic second president Suharto, staining the books and the tables they rest upon. The tarnished books allude to Suharto’s 1966 ban of communist literature, including Pramoedya’s works (upon his arrest a year earlier, his library was looted and burned). More broadly, Darmawan’s extraction kits conjure up technologies that, in the hands of European colonizers, and later Suharto’s New Order regime, converted the archipelago’s plant life into commodities for the global market. Beginning in the 16th century, spices like nutmeg, a coveted preservative, were warred over by the Portuguese, Dutch and British, becoming alibis for territorial acquisition.

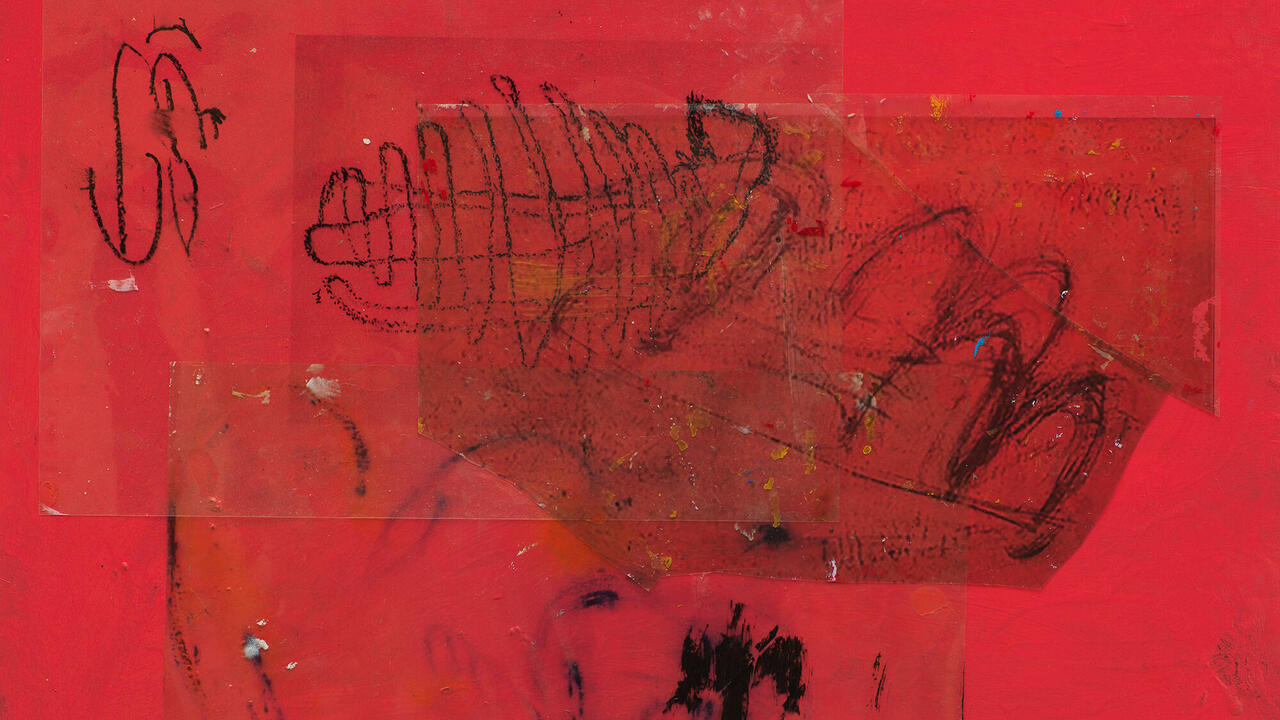

On a wall behind the desks are eight drawings on coated book paper (Lexicon of a Lexicon of Foreign Artists Who Visualize Indonesia, 2024) that show thriving foliage changed into monocrop plantations. Darmawan made these using an AI image generator trained on pastoral landscapes – however, he added in belching smokestacks and workers performing backbreaking labour. His fake images speak both to the extractive nature of AI and to the ways in which colonial representations are a kind of ‘rumour’ or ‘folklore’ – as scholar Manu Karuka puts it in his book on the transcontinental railroad and imperialism, Empire’s Tracks (2019) – contrived to deny sovereignty.

At ROH, there are iterations of the same artworks, albeit with a swap. In this version of Tuban (2019–ongoing), the distillation kits are arranged on teak jengki furniture. Jengki, an adaptation of ‘Yankee’, is an architecture and design sensibility that first appeared in Indonesia in the 1950s in houses built by the oil company BPM (Bataafsche Petroleum Maatschappij), a subsidiary of Royal Dutch Shell. The style, a tropical take on mid-century modernism, is celebrated as an expression of Indonesia’s independence from the Dutch but indicates the United States’ burgeoning influence in the region.

To see both shows, I travelled by train, barrelling past Java’s volcanoes and rice paddies for nearly seven hours. In Empire’s Tracks, Karuka makes the case that railways propelled the development of resource monopolies. Likewise, Darmawan explores how different infrastructures are harnessed to reproduce coloniality. In doing so, he distils a thorny history, but leaves us with a question of incalculable value: How to reverse the tide?

‘Ade Darmawan: Water Resistance’ is on view at Cemeti - Institute for Art and Society, Yogyakarta, until 3 August and ROH Projects, Jakarta, until 4 August

Main image: ‘Ade Darmawan: Water Resistance’, 2024, Cemeti - Institute for Art & Society, exhibition view. Courtesy: Cemeti; photograph: Kurniadi Widodo