Ann Craven

Klemens Gasser & Tanja Grunert, Inc. New York, USA

Klemens Gasser & Tanja Grunert, Inc. New York, USA

Ann Craven's painting Winner (all works 2002) depicts a peach-pink budgerigar looming towards us like a diminutive Godzilla. Set against a brilliant blue sky, it assumes an almost monumental presence that is at once comic and slightly menacing. Like Jeff Koons' giant floral Puppy (1991), Winner presents the unsettling spectacle of absolute innocence rendered unexpectedly powerful and imposing through an unnatural change of scale. It's a simple enough conceit, but an effective one, which unfortunately makes the remainder of Craven's new body of paintings feel all the more inadequate.

Flanking Winner in the gallery's front room are a series of depictions of fawns picking their way, as fawns are wont to do, through idyllic, sun-dappled clearings. Most of the brushwork in Gray Day (The Life of a Fawn), Little Dear, Dear and In the Daisies is suitably effortless and airy, but a hint of self-conscious tricksiness creeps in with Craven's deliberate blurring of foreground and background. The suggestion of rapid movement and the immediately visible influence of photography are somewhat at odds with the tranquil and traditional nature of the image, but the disjunction is so slight that the impression it leaves soon fades. Craven's occupation of an ambiguous middle ground is a well-intentioned attempt at subtlety that, sadly, comes off as mere indecision.

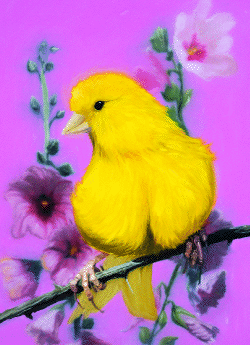

In the main gallery eight large and two smaller paintings return us to Craven's favourite subject: exotic birds. Again the artist employs a range of strokes to separate foreground and background, emphasizing the status of each painting as a montage of disparate elements. Thus birds and flowers are deliberately mismatched, their juxtaposition contrived rather than observed. Craven's feathered friends are of the cutest, kitschiest varieties, orange, yellow and blue, backed by orchids, roses and berries. She is also not averse to inventing her own sub-species, but even those birds that she renders unaltered look fantastic, unreal. Her paintings' saccharine, rose-tinted aesthetic alludes to an idealized view of nature, hinting at the exploitation of non-human life for all-too-human ends - from the keeping of pets to the destruction of the rainforests - but the context is so spare that potential interpretations are virtually limitless, any individual question that might have been worth pursuing drowned out by a twittering chorus of addenda.

Craven displays a fondness for working in series, and the show includes a number of virtually indistinguishable variations, such as Yellow Fello I and II and a triptych, Hello, Hello, Hello. Thus she holds out the promise of a genuine system, but delivers, in the end, mere formula. If her interest is in classification (with which ornithologists are traditionally obsessed), then her intent remains unclear. Lacking the zeal of a John James Audubon, she makes no attempt to exploit the diversity of her chosen species. If her compulsion to repeat is, as seems more likely, a post-Pop reflex action, we are still left searching for the beef. It is as if, in representing the same subject over and over again, Craven is attempting to discover within it, or invest it with, an emotional charge that never materializes. And while even this grimly alienated process might have commanded some interest of its own had it been enacted with a little more commitment, there's not enough here to suggest even this rather debased possibility.

Painters from Alex Katz to Elizabeth Peyton and Karen Kilimnik have been named as Craven's precursors, but the comparisons are mostly superficial. Sure, her imagery is girlish and sweet, and perhaps ironic‚ according to some nebulous, catch-all definition of the word, but as yet she lacks both the stylistic assurance and the endearing eccentricity of her elders. A recent on-line debate saw participants struggling to uncover Craven's motivation for making such fundamentally boring images, and concluding that their only possible value other than paying the gallery rent might lie in a kind of self-deprecating comment on 21st-century painting's fruitless search for a decent subject. Of course, were this the case, Craven would have made a pretty convincing argument for her own obsolescence and could now, by rights, retire to the country. But again, she simply isn't extreme enough. If anything, her real talent is for keeping us guessing, not through intrigue but through sheer blandness. The only test of the viewer contained in her work is one of endurance; exactly how long, it seems to ask, are you willing to go along with this? For the birds, man.