Apples and Pairs

Nicolas Party and Jesse Wine meet to discuss forms, frames and learning from Giorgio Morandi

Nicolas Party and Jesse Wine meet to discuss forms, frames and learning from Giorgio Morandi

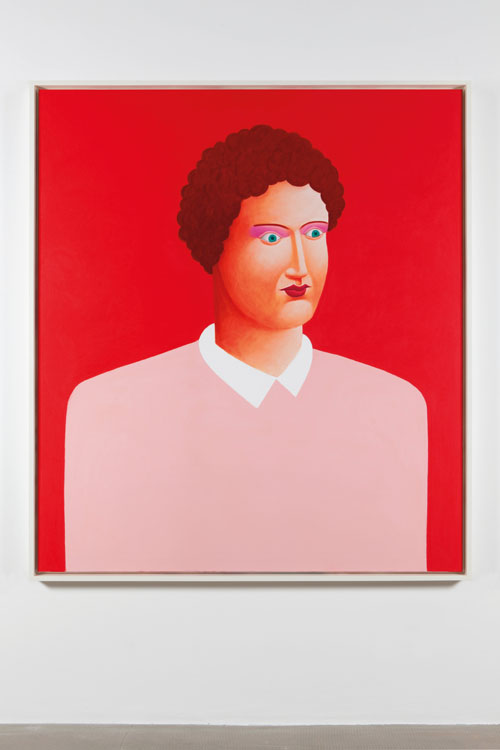

Nicolas Party is an artist based in Brussels, Belgium. He uses painting, drawing, sculpture and print-making to explore the infinite and unexpected possibilities of traditional forms (portraiture, still life) and banal objects (teapots, trees). Jesse Wine is an artist based in London, UK. He works mainly with ceramics, creating pieces that often act as a form of self-portraiture or pay direct homage to art history. Ahead of ‘Snails in Notting Hill’, a collaborative installation at Rise Projects, London, featuring crockery by Wine and wall paintings by Party, the pair met to discuss forms, frames and learning from Giorgio Morandi.

JESSE WINE I saw your exhibition ‘Boys and Pastel’ at Inverleith House in Edinburgh earlier this year, which was the first time that I had properly encountered your work. The show included large-scale wall paintings and also a number of framed pastel works. The first thing I thought was: why are they framing these? I was perplexed that they were behind glass because I wanted a greater sensory experience of the surface, how fragile it is.

NICOLAS PARTY There are different kinds of frames. In ‘Boys and Pastel’, the murals surrounding the pastels formed one kind of frame. In very practical terms, you need to put pastels behind glass: they’re so fragile that if they get knocked, or if you touch the surface, you destroy them. But I am also interested in broader questions of presentation and the spaces in which artworks are ‘framed’. When you make art, in the back of your mind you always have the idea that it’s going to be exhibited somewhere, maybe in various places, and these different contexts will necessarily influence how the work is perceived. Throughout history, painting’s ‘natural habitat’ has changed: from the church to the salon and now to the white cube. I think frames probably started to disappear when we began showing art in all-white galleries. Before that, paintings would need a frame to separate them from what was going on behind them, on the wall, which would be coloured or wallpapered or whatever. The frame was crucial: without it, you couldn’t see anything.

In my case, I use frames because I think my compositions in themselves are very self-contained. It’s not like in photography or in the cinema, where it is implied that there is a world beyond what you see and the camera is just showing a very small section of a wider image. In a painting, there is nothing outside. The way in which Giorgio Morandi composed his pictures has been very important for me in relation to this: his objects are always in the centre of the canvas, like a group of performers on stage.

JW Morandi is an interesting example. I’m sure you get asked about him a lot, in terms of your choice and arrangement of objects.

NP I paint still lifes and I often paint pots; Morandi is a great source of inspiration. Paul Cézanne is important, too: his apples are another example of a classic subject repeated as a way of experimenting with shape and light. For me, though, the most important lesson from Morandi is how to focus. His paintings are telling us: there are no bottles outside of the frame, so concentrate on looking at the ones in the picture. It’s a very difficult exercise to look at an object with a great deal of attention – to look only with your eyes and try to forget what you are looking at. John Cage was asking us to do the same thing with sound in 4’33 (1952). He was saying: forget to hear – melody, the sound of a car – you need to erase all that information. Then, you can really listen.

Another amazing thing about Morandi’s painting is the texture of his brushwork. He worked with a size of brush and type of paint that registered all the movements of his hand directly onto the canvas, using his wrist to make these little waves, so it seems as though the paint is always moving, all the objects are moving. It’s almost like a seismometer but, instead of tracing the Earth’s movements, he captured the vibrations of the pots. For years and years, Morandi looked at the same vases every day and – I think – he increasingly had the sense that matter is moving, which, of course, is absolutely true. Nothing is still; on an atomic level, things are in constant motion. It’s also a question of entropy and decay: every object is turning into something else very gradually. If you leave a bottle for 5,000 years, there will be a profound change. Morandi was so concentrated and focused – so totally immersed in what he was looking at – that he saw this.

JW What is the relationship between the portraits – the ‘boys’ – and the other works in ‘Boys and Pastel’? From what you have been saying, there’s not such a difference between inanimate and animate objects for you. The pieces of fruit in your still lifes would be a case in point: they are painted almost like characters. Fruit is clearly alive, in a sense, but you bring it to life in a different way.

NP The portraits that I’m painting are not real people; they are as alive as the other subjects that I’m painting. Morandi was painting pots and, when we look at his works, we have a conversation with them. That’s the beautiful thing about art: you can ask the viewer to have a conversation with a black square or a blue horse.

JW When we were talking earlier, you said something that I thought was quite interesting, which was that you are searching for motifs that are personality-less. You used the example of a tree.

NP It’s not about trees lacking personality; they have a lot of personality. It’s more that people have been drawing and painting trees from the earliest days of mark-making. A tree is something that you will never get bored of looking at or thinking about. A portrait is the same. There is something incredibly rich about these very familiar subjects that have been used throughout the history of representation.

I like Italian food: you just need some pasta and tomato sauce. But, as every Italian will tell you, it’s actually very difficult to find a place where you can eat a good bowl of pasta with tomato sauce. A portrait or a picture of a tree is the same: it’s easy to make a bad one.

JW I’ve been thinking a lot recently about the British education theorist Ken Robinson. His position is that we are educated out of creativity: we all start life with wonderful imaginations and then we go to school and we are taught that actually there’s a structure to things and that you must do it this way. Even if you get back some of that creativity at a later stage, your relationship to it has changed because the way you value being creative has shifted – you are viewing it through the filter of art school or the commercial world or adult relationships. For the past few years, I’ve been working mainly in ceramics, and maybe part of that stems from a desire to reach a more intuitive way of making. Occasionally, people can tap back into that naive creativity with amazing results. Think about Henri Matisse’s cut-outs. It was as if he couldn’t get it wrong; he could only get it right.

NP That’s because there was no discussion about it for him; it wasn’t about them being good or bad. When cutting the paper shapes, he was not trying to do beautiful shapes, beautiful colours, he was just making them. It was something very absolute.

JW Last year, I had my first institutional show at baltic in Gateshead and, when I did a site visit, I was really surprised by the number of primary-school children that visit the space. I thought it was an interesting opportunity to communicate with people outside of my usual audience, so I decided to make puppets: ceramic items of clothing, hats, shoes, rucksacks etc., which I presented like Alexander Calder’s mobiles. You know, Calder was a puppeteer. While he was living in Paris in the late 1920s he made a whole puppet circus that he performed in front of people like Jean Cocteau, Le Corbusier, Fernand Léger and Piet Mondrian – the whole European avant-garde.

I feel that my work communicates things very immediately and very openly – and there is a sense in which yours is similarly accessible – but I wonder if it sometimes suffers, in the context of the contemporary art world, because of this.

NP When I was a teenager, I painted a lot of landscapes of the area where I grew up – a small village by a very beautiful lake in Switzerland. I spent my time copying the labels on wine bottles and painting watercolours of the vineyards and the mountains. When I started art school, I became infatuated with a completely different kind of work, which was all very new and exciting, and my style changed. My parents came to one of my early shows and they said: ‘Oh … We don’t understand it but we’re sure it’s good. It’s just not for us.’

I didn’t like the idea that what I was doing had suddenly been put in a very specific ‘art’ context and had become something that my parents couldn’t understand, or didn’t want to. Sometimes, I look at the paintings that I did of the lake and I think they’re good, even if they seem quite simple. Now, I think I’m closer to that. My parents say: ‘Your trees look beautiful,’ and they mean it, and that’s great.

JW Is it a kind of seduction – to get people to engage with the work? Because I find your work totally seductive.

NP Seduction is important. I see it as the way to get people into the work, a way to get them into a conversation. Ugliness can be a form of seduction, provocation is seduction, beauty is seduction.

JW One way I try to get people to engage with my work is to install it so that the pieces take a while to get around physically – that way viewers are forced to spend more time with it. At Inverleith House, you worked with the space in a very deliberate and effective way: for instance, using the doorways to frame various compositions. You might glance back through a doorway to one of the portraits of boys to find him looking back at you: this exchange of glances made me pause; it changed the rhythm of the show.

NP When you make things that people feel they ‘get’ in two minutes – or even less, two seconds – you have to think harder about how you put those works together. People often assume that someone with flashy, sexy clothes won’t be smart. So, if your work is a bit flashy and sexy, you need to find another way to make your point. I try to do that by pairing very straightforward things in a surprising way. Take the title of our show at Rise Projects, ‘Snails in Notting Hill’: that is a good combination.

JW When I was in art school, one of the tutors, Brian Griffiths, told me to give up on making what I believed to be an original form, and instead to focus on where two surfaces meet, because that’s an opportunity to be original. And those surfaces might manifest themselves as two words in a title, or two works together, or an exhibition and a text.

NP Sometimes, you just need to put simple things together. And, from that point, it becomes interesting. It’s a bit like tomato and basil, or two people together. It’s a bit like love.

Nicolas Party is based in Brussels, Belgium. In 2015 he has had solo shows at kaufmann repetto, Milan, Italy; SALTS, Basel. ‘Snails in Notting Hill’ runs at Rise Projects, London, UK, until the end of November.