'Art After The End of Art'

London School of Economics, UK

London School of Economics, UK

With the publication of his 1964 article ‘The Artworld’ in The Journal of Philosophy Arthur C. Danto heralded the end of art’s previously inextricable relationship with aesthetics. For a conference dedicated to the assessment of aesthetics’ survival today he is not, therefore, the most likely of campaigners. Yet Danto has never been a doomsayer; his end is not a death. Indeed, since his all-important encounter with the Brillo boxes of Andy Warhol, Danto’s project has been one that elaborates a theory of art effectively reborn by his declaration of independence from the bedevilment of aesthetics. For his first trip to London in over 20 years Danto, who is the Emeritus Johnsonian Professor of Philosophy at Columbia University, took the opportunity to reconsider his Pop art point of departure and adjudge the legacy of rescinding the rule of Clement Greenberg and Kantian aesthetics.

Drawing its subject from the title of his 1997 book Art after the End of Art, the day-long conference sought to consider Danto’s work not ‘as a closed body within/about which we would have to talk but as a starting-point and a reservoir of potentialities’. Richard Shusterman, Professor of Philosophy at Florida Atlantic University, began the day with his critique of ‘disinterested’ aesthetics via a consideration of the erotic arts of China and India. Citing Michel Foucault as the only Western philosopher to acknowledge the proximity of the sexual subject to the aesthetics of existence – even Nietzsche denied that sexual activity could be pretty – his analysis of works including the Karma Sutra demonstrated that aesthetic prudishness was a peculiarly Western trait. Nicolas Vieillescazes’ ‘The Return of the Hegelian Repressed’ tracked the recent re-emergence of Hegel back to Danto himself, while Jean-Pierre Cometti, Professor of Philosophy at the University of Aix-Marseille, attempted to define an aesthetics of ‘usage’ in order to break the ontology of the art object.

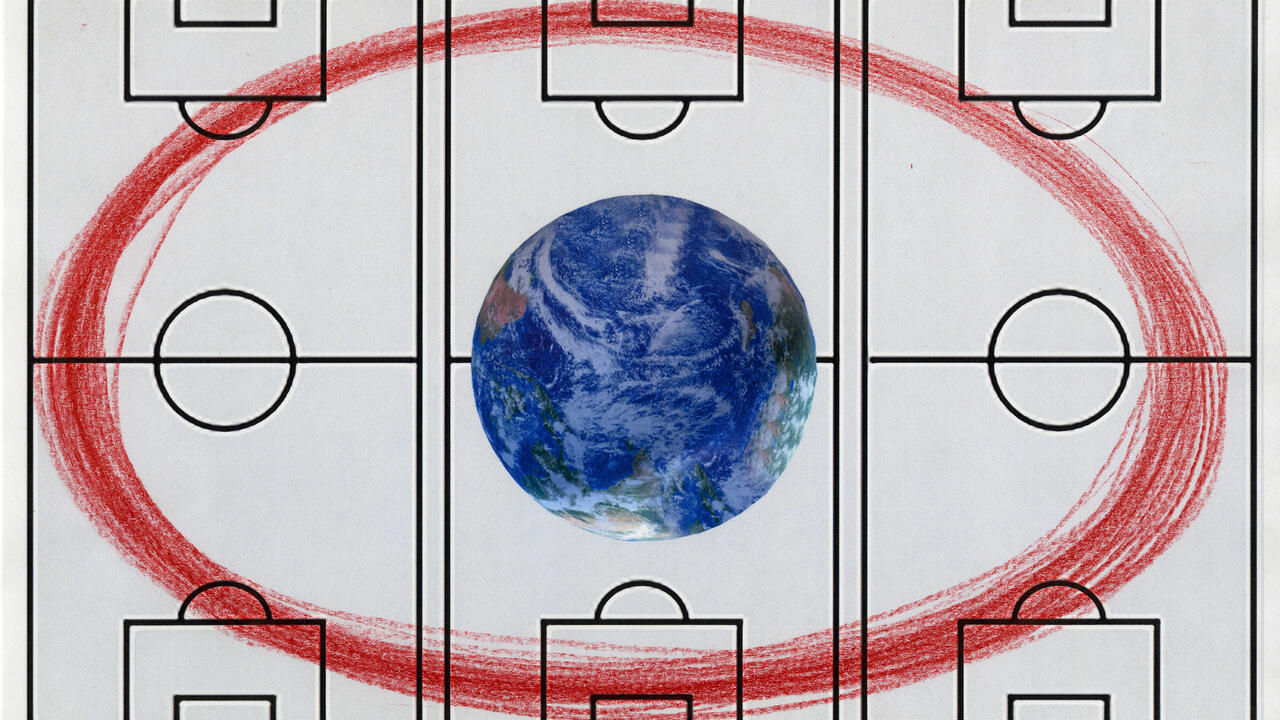

If, for Danto, it was the sight of red swirls on white packing boxes in an Upper East Side gallery that put ‘the boundary between the art world and reality in philosophical receivership’ in 1964, it was down to him to reappraise the importance of aesthetics to contemporary art today. Over 40 years later Danto remains secure in his rejection of ‘universality’ and ‘beauty’, yet he does not junk aesthetics with the force he once did. Finding a new interest in what he terms ‘internal beauty’ – that is, beauty that contributes to the work’s meaning – the day culminated in some form of reconciliation, if not with Greenberg then perhaps with Immanuel Kant. But the champion of the day was Hegel; indeed for Danto if beauty is not internal, it is effectively meaningless, the beauty of Marat being integral to the politics of Jacques-Louis David’s painting. Whether a Hegelian aesthetics of meaning has the ability to crack the timeworn teaser of form versus content remains for Danto to demonstrate.