The Art of Destruction

Getting tough on vandalism

Getting tough on vandalism

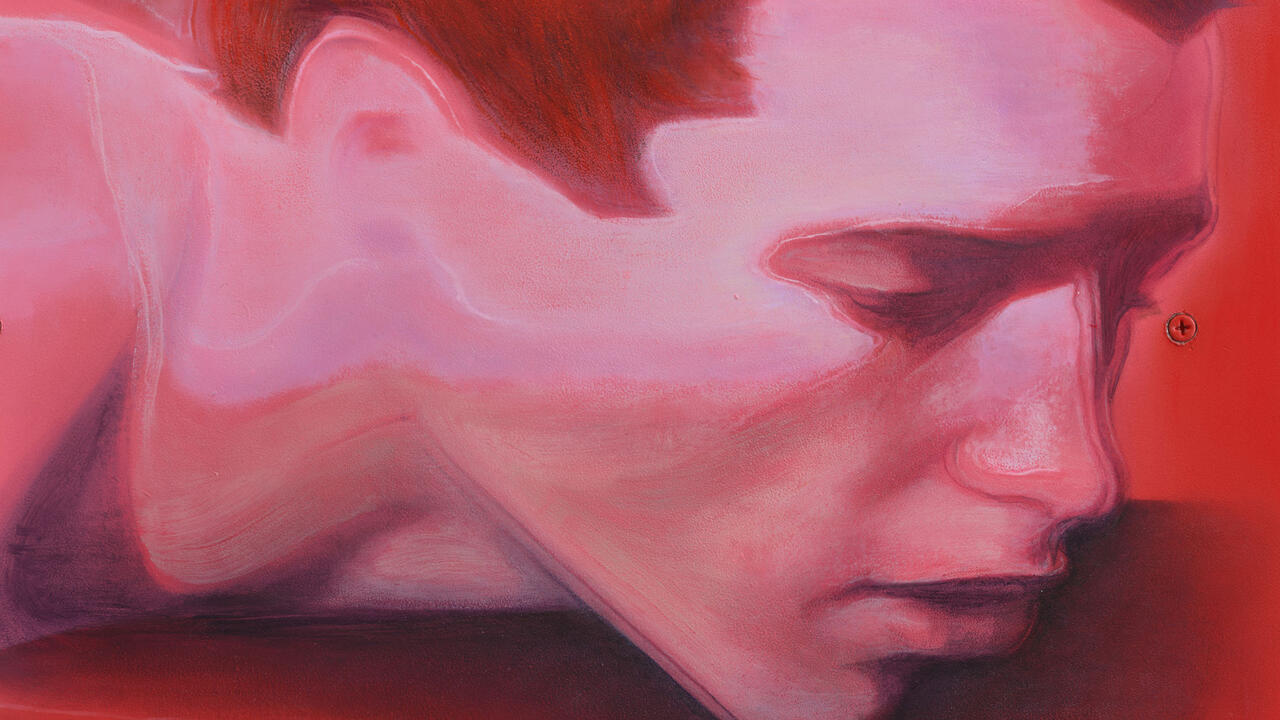

For me, an image is the sum of its destructions.

- Pablo Picasso, 1954

On Sunday, May 21 1972, Lázlo Toth, a 33 year-old Hungarian, attacked Michelangelo's sculpture Pietà (1498-9) with a hammer. Shouting 'I am Jesus Christ, Jesus has arisen from the dead,' he was carried out of Saint Peter's in Rome by a fireman, watched by a large crowd leaving the cathedral just after mass. Later, in court, he repeated that he was Christ, and developed a theological argument against the very idea of depicting Christ in the lap of His mother: God is eternal, hence can have no mother. A piece of art that gives expression to such blasphemy must be destroyed.

Toth's violent act, one of the most notorious examples of modern iconoclasm, had interesting repercussions. The Pope himself brought roses and prayed before the sculpture. The fireman was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Gregorian Order, because he had saved not only a work of art, but - in the Pope's words - 'the very symbol of the mother of God.' Reactions were strong in other quarters as well, although conflicting: Italian sculptor Giacomo Manzù demanded the death penalty, whereas a Swiss artist group applauded the action as a transgressive art performance, and tried to nominate Toth for the Golden Lion of the Venice Biennale.

This infamous incident is discussed in Dario Gamboni's The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution (Reaktion Books, 1997), a rich and highly interesting new study of the intentional demolition of art. Art historians have usually shied away from the topic, treating it as extraneous to art history proper, and ultimately as devoid of intellectual interest. Gamboni's central argument, however, is that vandalism of artworks often cannot be understood independently of certain artistic or theoretical aspirations, and, hence, can be fully grasped only through an art-historical approach. Of course, one can distinguish a great number of motives - political, feminist, theological, aesthetic, pathological, etc., for such acts. Vandalism directed against art may be an enigmatic and often bizarre theme, but - this is Gamboni's main point - it is not devoid of meaning.

Certain iconoclastic themes can be traced back to Antiquity and to the theological battles in the Middle Ages, but Gamboni's emphasis lies on the modern period which itself is initiated by an uncommonly powerful instance of Bildersturm: the French Revolution. Rarely has the idea that the old order must be destroyed in order to make room for a new one found expression in so drastic a fashion. Many Revolutionary prints show the figure of Time smashing symbols of the Ancien Régime.

The most rewarding chapters for readers interested in contemporary art are those on the destructive rhetoric of the avant-garde. Especially brutal quotations can be found, not surprisingly, among the Italian Futurists, who proposed to free Italy from its 'cancer of professors, archaeologists, and tourist guides and antiquaries' (Marinetti) by demolishing libraries and museums. But similar forms of iconoclasm also crop up in the writings of apparently less militant artists such as Pissaro and Malevich, the latter of whom, in 1919, claimed that the only concession to be made to preservationists was 'to let all periods burn, as one dead body.'

Can one claim that the iconoclastic rhetoric found in the manifestoes of the early avant-garde prepared the ground for actual destructions of artworks, and, in some sense, even legitimised some of these destructive acts? Gamboni analyses the 'metaphorical iconoclasm' of the avant-garde, but never suggests a direct causality between the destructive rhetoric and actual cases of vandalism. There remains a crucial difference between, for instance, Marcel Duchamp's advice, in the Green Box (1934), to 'Use a Rembrandt as an ironing-board,' and the actual execution of this destructive deed. To dream of the devastation of Picasso's Guernica (1937), like Antonia Saura, who wanted to 'open vaginas in the damned canvas' with knife - and actually to spray the words 'Kill Lies All' across the painting, as Tony Shafrazi did in 1974, also remain two different things. The latter act can hardly be legitimised solely by the fact that Picasso conceived of his own paintings as an accumulation of destructions. Sabotage is something separate from violent dreams.

So, why do people destroy art works in museums and galleries? Quite often the perpetrator tends to see the vandalism not as something entirely extraneous to the piece in question, but as a fulfilment of the work's inner possibilities, or even as a way of bringing it back to life. Thus, Shafrazi explained in an interview, 'I wanted to bring the art absolutely up to date, to retrieve it from art history and give it life.' And the German student who, in 1982, felt so threatened by Barnett Newman's Who's Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue IV (1966-7) in Berlin's Nationalgalerie that, in an act of fury, he struck it with his fist and foot, finally spat at it, and subsequently claimed that Newman, had he been alive, would in some sense have shared his opinion: 'I feel that now, for the first time, the picture is really complete, because of what I have done.'

These two notorious acts of vandalism, both treated by Gamboni, have been meticulously reconstructed by Felix Gmelin as part of the exhibition 'Art Vandals.' His project presents twelve iconoclastic moments in modern and contemporary art, from Rauschenberg's Erased de Kooning (1953) drawing, to more recent disasters such as Mark Bridger's destruction of Damien Hirst's Away from the Flock (1994), and Ed Brzezinski's devouring of a Robert Gober sculpture (1989). As a reminder of the fact that not all forms of art vandalism display the high-strung ambience of early Modernist manifestoes, a quotation from the New York Post is instructive: '"Okay, I was hungry," Brzezinski said, "I'd been drinking and I hadn't eaten anything all day." Brzezinski was at the Cooper Gallery to check out the new show of Robert Gober's work... "I noticed this bag of doughnuts sitting on a pedestal," says Brzezinski, who also works as a critic and curator. "Plain doughnuts with no sugar. I figured somebody had brought them and then gotten tired of them. So I grabbed one and bit it. It tasted stale."' 1

Gmelin's staging of the twelve carefully selected crime scenes treats the tradition of art vandalism as a series of readymades, ridding them of spontaneity and radicality. Thus, the iconoclastic violence of the avant-garde is neutralised by the art institution. What was once a heroic attempt to break out of a too narrowly defined concept of art becomes domesticated by the artist's aesthetic. Gmelin's works offer a succinct rendition of the predicament of the post-avant-garde: radical transgression is no longer a break with the museum, but, rather, part of what we expect to find in this modern house of worship. We expect provocation, and provocation we get, but in an institutionalised form.

Gamboni's inquiry into the iconoclastic element of modern art suggests an interpretation of sabotage as the very peak of Modernism. Reduced to its pure form, this is what the radical avant-garde art is all about: transgression. Do these words - 'transgressive', 'radical' - still have a meaning in today's art world? Some people seem to believe so. Russian artist Alexander Brener's vandalism earlier this year in the Stedelijk Museum, spraying a green dollar sign on Malevich's White Cross on Gray (1920-27), seemed to me an unusually pointless act of violence, with the sole intent of attracting attention from the media. However, Giancarlo Politi, editor in chief of Flash Art, sees things in a different light. Under the heading, 'Freedom for Brener: In the Name of Art', he contends: 'In my opinion, the arrest of Brener is an offence to the artist's freedom of expression and, as such, a repressive act. Brener is no hooligan, but a transgressive artist with a strong personality, just as much as Malevich was the same, in his own time.' 2

A transgressive artist - is he joking? Apparently not. Politi continues by designating Brener's dollar sign a 'particularly ambitious art work' with great 'aesthetic value.' So what, precisely, could the merit of this act of vandalism be, and what interesting border does it transgress? Compared to Felix Gmelin's cold reconstructions, Brener's brutal act appears as a regression to an already obsolete chapter of art history, and Politi's vapid defence seems to me little more than an old man's vain dreams of regained radicalism.

If it is correct, as Dario Gamboni claims, that the wilful destruction of art works is a legitimate theme for art historians and critics, then, of course, these acts must be assessed and evaluated, each according to its own specific conditions. From such a perspective, Brener's act of vandalism - presumably conceived as a critique of capitalism - may be viewed as an artistic project, but, as far as I can see, as a hopelessly poor one. There are interesting cases of iconoclasm, and less interesting ones. This is a low - even Lázslo Toth's holy rage seems preferable in comparison.

1. New York Post, October 5, 1989, quoted in Felix Gmelin, Art Vandals (Riksutställningar: Stockholm, 1996)

2. Flash Art, March/April 1997, p. 55