The Art World Goes Virtual

With physical spaces on lockdown, exhibitions and sales rooms are migrating online. Will they ever come back?

With physical spaces on lockdown, exhibitions and sales rooms are migrating online. Will they ever come back?

Galleries the world over have shuttered in response to the spread of coronavirus. It is unknown when they will reopen. And so the art world has found itself in a position of having to come up with new ways of functioning at a time of mass quarantine, closing exhibitions, delaying fairs, pivoting online.

The internet has predictably emerged as a short-term solution. When Art Basel cancelled its Hong Kong fair, it took business into the cloud with its own online viewing room. Galleries set about making their own curated offerings to attract buyers, though these amounted to little more than a slideshow of JPEGs.

These efforts have since spilled outwards. Within the last two weeks, numerous galleries have launched virtual offerings: Pace Gallery, quick off the mark, opened an online exhibition of Saul Steinberg’s work on the theme of domesticity. (Next up: a group presentation on the theme of ‘stillness’.) Hauser & Wirth, meanwhile, has opened its first ever online exhibition, of Louise Bourgeois's drawings, as well as a series titled ‘From a Distance’, encompassing video messages from the homes and studios of artists under lockdown, including Luchita Hurtado, Mark Bradford and Martin Creed.

‘From the first shock, to the first calls, to the first idea, to putting it online was barely a week,’ Iwan Wirth tells me over the phone, explaining that the crisis has meant reframing digital material as the main event: ‘They were created to support a one-to-one, in-the-flesh experience with the work. All the digital content was there to support the analogue experience. We’ve now turned it around. But how sustainable is it? That’s the question.’

It’s a similar story wherever you look. White Cube says it will be launching ‘digital initiatives’ in the coming weeks; Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac will be bringing online a current exhibition of work by Harun Farocki and Hito Steyerl; David Zwirner, which in 2017 became the first commercial gallery to establish an online viewing room, is going to ‘dramatically increase’ their number of these, as well as ‘transitioning some planned physical exhibitions to the online space,’ according to Elena Soboleva, director of online sales. From 3 April, the gallery will also be hosting 12 smaller New York-based galleries on their online platform, offering free digital real estate to operations with fewer resources to take exhibitions immediately online. Sadie Coles, meanwhile, is planning to feature online walkthroughs of current exhibitions by Sarah Lucas and Jim Lambie, as well as launch a new Instagram project, ‘Answers from Isolation’, centred on interviews with the gallery’s artists, friends and collaborators.

‘It is clear that things are not going to be the same, and we will all have to think about presenting works, exhibitions and projects in ways that we would have never imagined,’ Coles tells me. She says the ‘unprecedented pause’ is an opportunity to re-evaluate how the gallery operates: ‘I am sentimental about having a space in which I present the new works of an artist with whom I have a close and meaningful collaboration. I don’t believe that basic model will cease to exist but the scale on which we were all operating may well.’

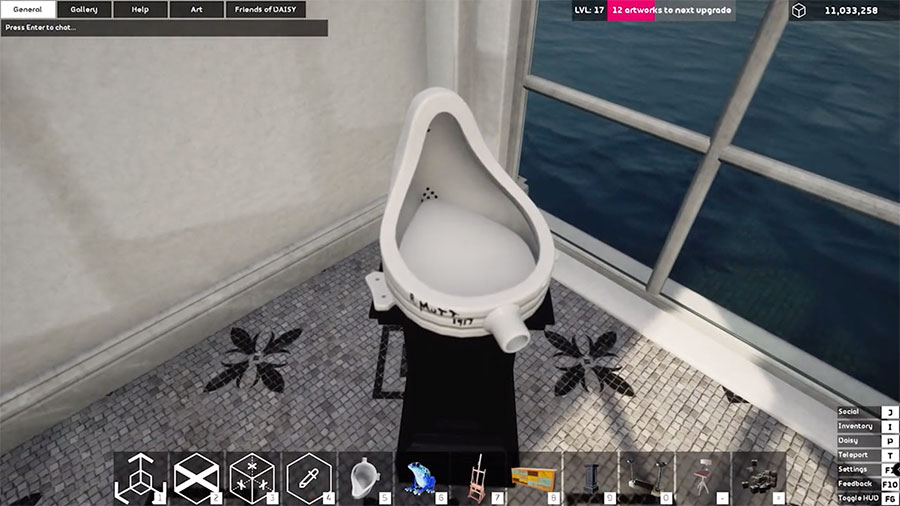

While online exhibitions tend to be curated web pages of images and video – media that shine on the flattened space of a laptop screen – there are also organizations exploring how virtual reality and game spaces could support, or subvert, galleries. In a somewhat Ballardian move, Hastings Contemporary, for example, has partnered with Bristol Robotics Lab to offer gallery tours conducted via two-wheeled videoconferencing machines. An operator and up to five people will be remotely led at a time through the gallery, taking in its exhibition and its views of the English Channel. Even less bound by physical space is Occupy White Walls, which bills itself as a massively multiplayer online (MMO) game, built around the idea of designing a fantastical art gallery. The player constructs a space, much as they would in The Sims, then chooses artworks to fill their halls and courtyards. Recommendations are algorithmically plucked from a database by the system’s ‘Art Discovery AI’, based on other artworks you’ve looked at while playing the game.

Yarden Yaroshevski, founder of StikiPixels, the company behind Occupy White Walls, says this setup is intended to give equal weighting to public domain masterpieces and pieces by new artists: ‘A big part of our vision is we don't want to be gatekeepers. I don’t want to decide if someone is a good artist or a bad artist. In a way, because of the AI, it makes this decision superfluous.’

It’s free to experience, although artists have to pay US$9 for submitting an artwork into the system. There are no sales made directly in the game, although Yaroshevski points out that artists retain all rights over their artwork and there is simple linking between an artwork and an artist’s website, with no sales commission. The project has been in development for some time, but in recent weeks Yaroshevski has launched a Kickstarter for raising additional funds and has also apparently received interest from a gallery about collaboration.

Also experimenting with the potential of a virtual gallery is The Zium Project, which has so far released The Zium Museum (2017) and The Zium Garden (2018). Each was a group show, with the latter including the work of close to 60 artists working with digital assets, spread across a sprawling, physically impossible, three-dimensional space. The project’s creator, Michael Berto, tells me that, with so many now locked to the internet as the final connector to the real world, there has been no better time to examine the future of art in virtual realms.

‘For people to be able to engage and interface with the internet as more than just “where the social media is located” and to get back to a place where the internet is a bit of a beautiful, historic, wholly unique anomaly of human creation, is a beautiful thought,’ he says. ‘These devices that we use every day, our computers, the internet, have so much more potential to deliver us into the connection, to art, to ourselves, to each other.’

The internet has long been an entry into the world and its connections are startlingly apparent at a time when accessibility to our surroundings has been dramatically reduced. But the current crisis is also exposing the limitations of digital infrastructure. In recent days, YouTube has lowered its default video quality to standard definition, in response to a possible bandwidth strain brought on by thousands upon thousands of people self-isolating. And any attempt to make a virtual gallery will also have to contend with technical barriers to entry, which are themselves tangled up in issues of class and access: Occupy White Walls, for example, might be free to experience, but it requires a powerful computer to run its graphically intense environments.

There is also the issue of who controls the underlying technology platforms. Arcade gallery in London, for example, is planning a live singalong karaoke version of a Marijke De Roover performance and is looking to commission pieces for online platforms and virtual spaces, but is also cautious of relying too heavily on Silicon Valley to reach audiences. ‘Currently we’re researching open-source platforms for multiple simultaneous online exchanges, so we don’t end up all being totally reliant on Google, Zuckerberg and co.,’ says Christian Mooney, the gallery’s founder and director.

Stefan Kalmár, director of London’s ICA, says ‘the current situation is less of a disruption than a sea change’, and makes a point that public cultural institutions have been in a precarious financial situation for some time. Whatever happens after lockdown, things are unlikely to go back to business as usual. Websites and social media might normally be put to work in the service of what Wirth calls the ‘one-to-one, in-the-flesh experience’ but, for now at least, they are the experience.

Main image: Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans, wwwwwwwww.jodi.org, 1995, homepage. Courtesy: the artists