The Artists Fighting for a Different Future in Myanmar

From re-interpreting protest symbols to selling work to support striking civil servants, how artists are responding to the military coup

From re-interpreting protest symbols to selling work to support striking civil servants, how artists are responding to the military coup

In the early hours of 1 February 2021, the Burmese military, known as the Tatmawdaw, arrested Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy (NLD) leadership in the Myanmar capital of Naypyitaw. On that morning, whatever future the people of Myanmar imagined for themselves was gone. As historian and political commentator Thant Myint U has observed, the coup was supposed to be a conservative reset of Myanmar’s politics but, instead, ‘may have inadvertently set off a new revolutionary era […] The country’s future is up for grabs.’

Since the National League for Democracy’s victory free elections in 2015, which seemed to herald the country’s movement towards democracy, artists in Myanmar have engaged in a Pavlovian struggle with self-censorship, conditioned by the fear instilled by decades of military dictatorship and state-sponsored suppression. In the period before the coup, a lot of the art made in Myanmar traded in typical landscapes and street scenes, and portraits of Aung San Suu Kyi – often painted in the same colour spectrum that makes the country so photogenic. I opened an art space, Myanm/art, in 2016 to support a younger generation of artists who were trying to move beyond a national identity obsessed by politics, looking at popular culture and global topics. However, the last two weeks has seen an incredible and immediate outpouring of protest art.

The symbol adopted a few days after the coup was the three-fingered salute. An indirect borrowing from the hit Hollywood series The Hunger Games (2012–15), it has become a rallying cry and an equalizer. No longer just disenchanted by the politics of the country, but now directly affected, millennial and Generation Z artists are leading an online movement to further the cause. Kyaw Htoo Bala, a 28-year-old art school graduate, created a sensation by inviting dozens of artists to contribute their version of the salute, breaking with the habit of self-censorship and inspiring thousands of other teens and twenty-somethings to speak out.

Other artists have referred to much older symbols of resistance. Soe Yu Nwe, a ceramicist from Yangon who studied at the Rhode Island School of Design created a drawing: a colorful rendering of a peacock in a tailspin, as if it was falling from the sky, losing its feathers in the process. The peacock is a powerful symbol in Myanmar – of royal lineage and freedom fighters. The bird is also the symbol of Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, and references her arrest.

Ku Kue, the first female graffiti artist in Yangon and a talented graphic designer, has been more direct in her approach. Her depiction of youth portraits holding the sign ‘You messed with the wrong generation’ is indicative of the anger and resentment felt by young people who have been given a taste of democracy, only to have it cruelly withdrawn. Thee Oo Thazin has gifted the the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) a collection of posters in both Burmese and English, with instructions to use their voice online, bang pots and pans at night to show their dissent and support the protests. Bart Was Not Here creates templates for poster art – one word graffiti slogans encouraging people to ‘Disobey’ or borrowing rap lyrics to mock the military in their grab for power. ‘You Need Us, We Don’t Need You’ is an artwork made to help propel CDM forward.

Artworks feature Burmese and English languages. English is familiar to the younger generations, whose social media platforms and exposure to global pop culture happily coincide with the well-known fact that the top generals do not speak English. Within a few days the newly established Association of Myanmar Contemporary Artists (AMCA) was on a Zoom call discussing the best options for standing together and creating artwork in the name of the cause. They set up what they call an Artist Street in front of the High Court in downtown Yangon, where they are painting in situ and selling artwork to support the civil servants who have stopped going to work in support of the CDM. The Artist Street attracts musicians and performance artists as well; the entire block has become the newest exhibition space in town. These first- and second-generation contemporary artists (born between 1960–1985) are more calculated in their practices, and their reactions to the military coup and its aftermath is sure to colour their artwork in the coming years. They are not among the keyboard warriors of a younger crowd, whose immediate anger and distaste for being silenced reverberates through their daily artwork shared online.

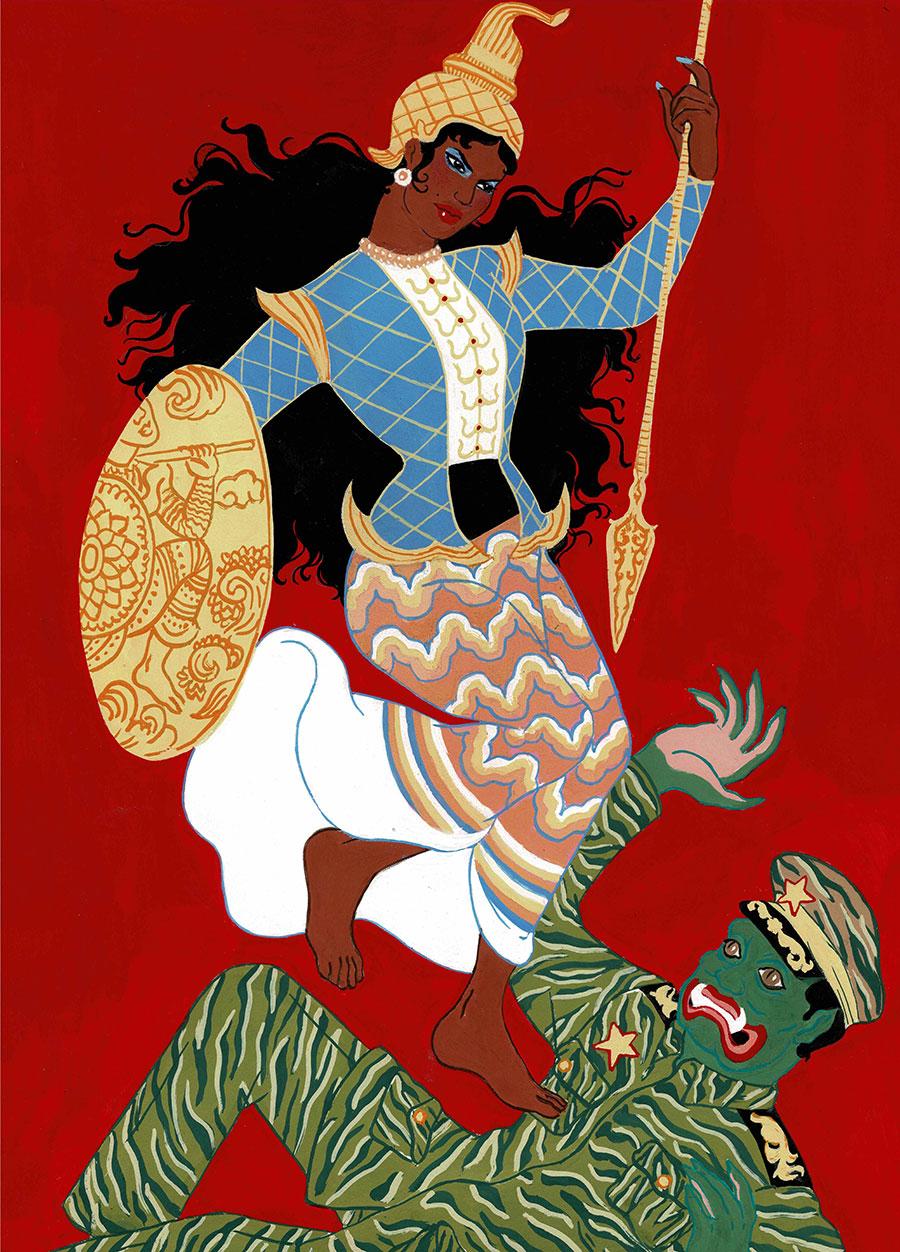

The latest piece that caught my attention amongst the hundreds of artworks currently being shared in the name of dissent is by Richie Htet. Known for his sensual portraits of mythological creatures from Buddhist and Hindu mythology wrapped in colorful textiles, Htet deliberated for a week before adding his own interpretation of the protest through his artwork. The dark-haired beauty ‘Mie Bamar Pyi’ is the national personification of Myanmar. With her spear and shield in hand, she is pictured as coming down on the Ogre – a common villain in Buddhist mythology – who is dressed in military general’s clothing.

Main image: Courtesy: Myanm/art, Myanmar