Ben Lerner on Margaux Williamson’s Hard-Earned Magic

The Canadian painter’s new work offers a ‘vivid experience of perception without vivid percepts’

The Canadian painter’s new work offers a ‘vivid experience of perception without vivid percepts’

The Hinge

I don’t think I’ve ever seen Margaux Williamson paint a computer before, but there are several laptops in her new works. The laptop on which I’m writing this feature can open to approximately 135 degrees and I usually have it tilted back all the way. I do this because it gestures towards a flat page on a horizontal surface and reminds me of being hunched over a sheet of paper, writing by hand – something I almost never do anymore. I don’t have a desktop computer, so I am never before a screen that’s truly perpendicular to the desk. With my oblique laptop, I feel like I’m occupying two perspectives at once – I’m above the screen but also before it, looking down yet facing forward – which means I’m not fixed in one position; maybe that helps me write, frees me from a single grammatical perspective.

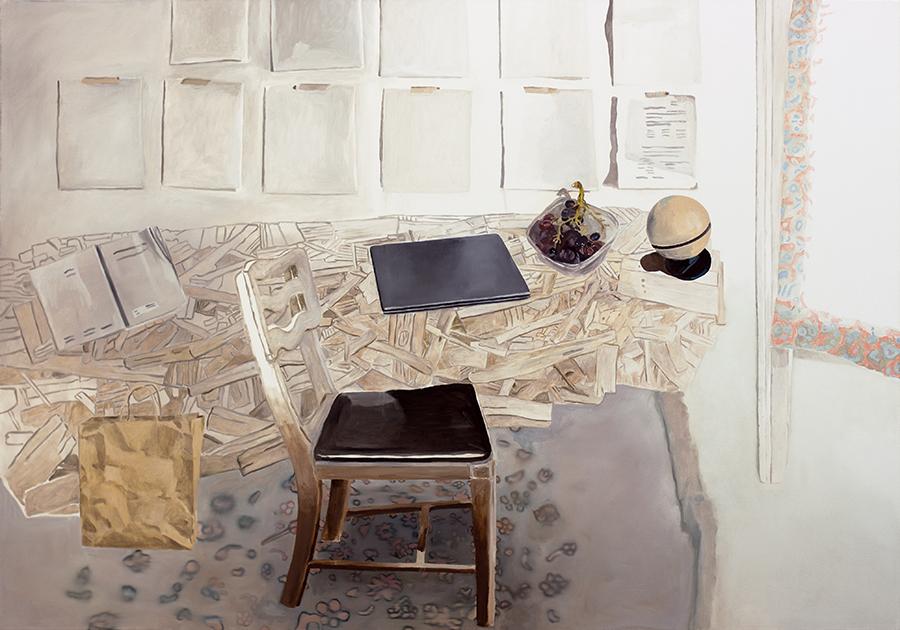

This condition of being suspended between points of view – of being both above and before, hovering over and facing – is crucial to Williamson’s work. Like a laptop, the horizontal and vertical planes in these paintings are hinged. I can peer straight down at the marks scratched into the wood in Desk (2020); I am somehow directly over the beautiful blue and white plate, but the manila folders have started to angle back, to recede in space, and the pile of books above the folders is stacked more or less flat on a horizontal surface – although I can’t tell if the white shape is part of the cover of the top book or an object resting on it.

It’s both and neither. (Similarly, in Table and Chair, 2016, you can look down at the table from above yet see the fore edges of the books stacked atop it.) This interplay of the horizontal and the vertical is explicit in Window (2017), in which pieces of paper are taped to the wall: a horizontally oriented medium made vertical, like a painting. A manuscript lies open, flat against a table, but this table, instead of being perpendicular to the wall, seems to nullify the distinction between wall and floor altogether. (A globe – echoed in the globes of the grapes – suggests a possibility of spherical modelling amid these wonderfully troubled forms of flatness.)

Every Part of a Tree Respires

When I look at Tree (2020) – no, ‘when I look at’ already feels wrong. Something happens when I stand before it. It has to do with how the leaves are vague, blurred, merely paint around the edges of the canvas, but then swell towards me in the centre. And, as they come forward, I see – although it doesn’t feel like seeing exactly; it feels like a dawning spatial awareness not reducible to sight – great depths through the leaves and branches. I can see far into the recesses through which the dawning, or dying, light is visible. The leaves in the centre of the canvas are certainly more detailed and dimensional than the green areas around the edges, but they nevertheless remain abstract. A vivid experience of perception without vivid percepts; space becoming real without objects coming into focus. As a result, I’m less looking at the canvas than enveloped by it. (I’m enveloped by it even when I view a small version on my screen.) It’s no longer a question of the hand, but of the whole body. Here’s a strange thing about Tree: standing before it, I can focus my eyes or relax my gaze, and nothing about the powerful experience is changed.

Or is it more disorganizing than what I’m describing? Is it that I have this experience of projection (leaves coming out) and recession (the distances glimpsed through them) in a way that exceeds my body, dislocates it, so that my sense of self dissolves? I am distributed across what I’m seeing, my vision or consciousness scattered like ashes within it. I am the tree seeing the tree seeing me. I realize I’m at the edge of sense here. When I was little and played hide and seek with my brother, I sometimes hid in the bushes in front of our house on Jewell Street. Sometimes – either because he couldn’t find me or he was playing a trick on me – I would be there for ages, night beginning to fall. I’d be there for years: the stems growing into me, finding my veins, one big respiring network now, the wind moving through me, a thousand red berries that were my eyes.

Detached from Surface but in Space

Tonight, I have read Crockett Johnson’s Harold and the Purple Crayon (1955) to my daughters one billion times. Harold uses his crayon to draw a landscape he then occupies: boats and balloons he can ride, a city he can get lost in. Eventually, he draws his way back to bed. I remember how, when I first encountered Harold, I was still accustomed to grasping a crayon, did it many times a day, knew intimately the feel of pressing the wax against paper as I drew and, maybe, formed letters. When I first fell in love with the book, writing and drawing had not yet separated out for me; I could approximate letters, but I formed them as if from the outside, sketching their shapes. (In Williamson’s new paintings, text is always reabsorbed into drawing, abstracted into undifferentiated lines.) At the age of five, as I lay on my Star Wars sheets looking at Harold, I was still a visual artist. I could feel in my wrist and hand the lingering pressures of the day’s crayoning. This intensified my imaginative identification with Harold and his ability to transform the blank page of his room, to make rudimentary line drawings that became their referents in an enterable white space. These days, I draw again with my daughters but, between my adolescence and 2014, I don’t believe I drew anything at all, ever, let alone with crayon. I was only writing. When I see paintings with my painter friends, they relate to the artist in the way I remember relating to Harold, albeit in a much more sophisticated and less fantastical manner; they can imagine the moment of creative contact, how the application of mark to support might actually feel.

I think about Harold now for two reasons. First, because Williamson has a grownup, hard-earned version of his magic, although she wears her sorcery lightly. She manages to depict surfaces in such a way that they emerge independently as patterns no longer subordinated to particular objects: the tables with their various grains of wood, the scalloped forms of leaves or waves, the designs in carpets, the inexact repetition of bricks, the nectar guides in orchids, etc. The surfaces often detach as autonomous patterns, yet they do not simply flatten her paintings into wallpaper or make them quilt-like; instead, these freed patterns remain in pictorial space. Harold’s magic is to make two-dimensional line drawings that operate as three-dimensional objects; part of Williamson’s magic is to produce a pure pattern I nevertheless experience as having more than two dimensions. (Sometimes, the pattern rushes back to be the surface of a figure again just in time to keep the spatial logic of a room intact.)

I think of Harold also because, when I look at Williamson’s paintings, I feel inside the process of painting. I briefly feel as though I could have made it. This is preposterous; I don’t know how to paint at all, and I don’t even know how to describe in language the real steps involved in producing even the most basic passages of Williamson’s work. (I couldn’t really do what Harold did either, but I could imagine it vividly because I was intimate with his medium.) Still, I don’t just feel like I’m looking at her canvases; I feel I am building them along with her. This is, in part, the result of her ability to make space haptic, an effect of the paintings’ particular ways of enlisting participation in their spatial articulation. But part of it is more tonal, has to do with her unaffected frankness as an artist. There is a certain kind of genius that doesn’t ask you to congratulate it for the tortuousness of its process, that communicates its vision openly, that shares its code. This lets me forget, for a moment, that her virtuosity is utterly alien to me and I get to inhabit what I take to be her vantage, even the time and textures of her making. And this gives me a version of the primordial thrill I experienced reading Harold and the Purple Crayon back when my hand still knew the press of a crayon on paper as a way of making other worlds. Williamson’s paintings make creation feel possible again. Her reach is briefly mine, is yours.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 213 with the headline 'Light Sorcery.

Main image: Margaux Williamson, Tree (detail), 2020, oil on canvas, 160 × 229 cm. Courtey: the artist