Black Belt

This intelligently conceived show set out with one of the fresher curatorial ideas of late: to examine the relationships between Asians and African-Americans in American urban life as manifested in the black fascination with martial arts and Eastern spirituality that began in the 1970s. This cross-cultural bleed - in both directions - found expression in music and film, such as Carl Douglas' Kung Fu Fighting (1974) and Bruce Lee's Game of Death (1978), and has continued through to current popular culture, from the Wu-Tang Clan to the Chris Tucker and Jackie Chan Rush Hour movies. We see the figure of Bruce Lee, a peaceful figure of resistance pushed to violence only as a last resort, as a major locus of Afro-Asian cultural interaction both then and now.

Following a smart hunch, the exhibition's curator, Christine Y. Kim, discovered that a number of artists had unformed interests in Afro-Asian subject matter; some, such as Patty Chang, had already made work in this vein but hadn't felt ready to show it. (In the case of Chang's flat-footed re-enactment of the Bruce Lee v. Kareem Abdul-Jabar showdown at the end of Game of Death, this trepidation turned out to be well founded.) The overall impression the exhibition gave was of artists struggling to personalize a topic of rich academic interest, most of them taking their cues from popular culture's simplistic constructions. Too many engaged with the themes of the show without creating any new meaning, and at a general level that often amounted to little more than simple pastiche.

David Diao, for example, is content to place an image of Bruce Lee in action alongside an image of Pollock action painting, dumbly comparing one's punch with the other's fling of paint. Iona Rozeal Brown's thugged-up late Edo portraits, such as a3 #10 (down-ass emperor Qianlong) (2003), depicting some supposed Qian dynasty royal in a Fubu jersey and cornrows, read like an uninspired academic aside to the cultural phenomena of blackface among Japanese teenagers and the popularity of ghetto style among Asian-American urban youth. Glenn Kaino created a video game version of the famous Game of Death fight scene, for some reason employing his face on Bruce Lee's character, and using Mark Bradford's for Abdul-Jabar. So little actually happens that you have to wonder if the game might not be broken (the bored guard who played it with me assured me that it was not). Worst of all was Y. David Chung's lethargic animation of some generic Lee fight scene, which dresses up poor drawing with a tech fetish to go absolutely nowhere.

Other contributions were formally more sophisticated but still didn't have much to say. Featured near the show's entrance was Sanford Biggers' portrait of black martial arts star Jim Kelly in black and white rice. Elsewhere the artist had suspended Chinese slippers from bling-chains strung overhead in the gallery, recalling the practice of tossing sneakers over telephone wires on street corners. With almost formulaic precision Biggers conflates distinctly Asian and black social and formal references. No questions are asked, no opinions are offered. Kori Newkirk's neon Ninja stars sticking into the wall are similarly vague, visually interesting but vacant; Luis Gispert's motion-sensor audio chamber is startling, but the fun is brief. And in a masterpiece of laziness from a normally wry Conceptualist, David Hammons placed a gong in the gallery, accompanied by the obtuse explanation 'Rap music and kung fu have the same level of madness to me. They're not about cultural exchange'. Was he forced to participate?

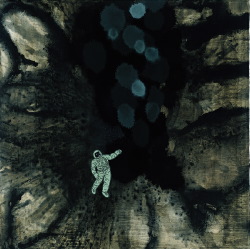

The best pieces in the show were somewhat distant from the subject matter chosen by the majority of the artists. David Huffman's airy canvases are like black Jules Verne fantasias peopled by Afro-Futurist spacemen, drawn over layers of gauzy washes that suggest Chinese landscape painting. For Live Evil (2003) Paul Pfeiffer demonically abstracted Michael Jackson into a Baconesque Indian miniature that slithers back and forth like some breed of Star Wars monster we've created. Ellen Gallagher's new series of five handmade 16mm projections done in collaboration with Edgar Cleijne, Murmur (2003), were made frame by frame, in some cases by scratching directly into the negative. Each is characteristically labour-intensive, and maintains Gallagher's uncanny feel for texture which is evident in the surfaces of her mutilated drawings, or those of her paintings included here. An appropriation of old sci-fi footage, in which aliens seem to be replacing humans, injects fear into the hybridization motif of the show, otherwise assumed to be something to celebrate unconditionally.

Are we to take the artworks in this exhibition as analyses of Afro-Asian cultural affinities, or as cultural products that in themselves form a part of the larger phenomenon? Kim seems to favour the latter, offering 'Black Belt' as an exploration of this polycultural realm not as it is perceived, but as it is formed. Such a distinction, however, is neither tenable nor flattering in this case. As analyses, the works here mostly offer too little in the way of assessment, and take too few positions. But as pure cultural products - culture 'as it is formed' - they contain less food for thought than the bulk of films and music that are bred from Afro-Asian cross-pollination. What makes art a vital but separate corollary to popular culture is self-awareness (though not irony, per se), an ability to integrate making with perception in a way that usually begets a kind of criticality. With that largely absent in 'Black Belt', one was left to imagine what might have come of a more focused show, organized with a tougher curatorial hand.