Blonde Bombshells

Marilyn Monroe and drone warfare

Marilyn Monroe and drone warfare

On the 26 June 1945, Private David Conover of the US Army’s First Motion Picture Unit visited the Radioplane Company factory in Burbank, California, founded by British actor and aviator Reginald Denny. Sent by the so-called Celluloid Commando (motto: ‘We kill ’em with fil’m’), Conover was on assignment to gather Rosie the Riveter-style images of women at war for propaganda purposes. There, he discovered a 19-year-old woman assembling engines. Her name was Norma Jeane Dougherty, later Marilyn Monroe.

Her photographer’s superior officer, Captain Ronald Reagan, went on to become US President, and the aircraft she was assembling – an OQ-3 radio-controlled Dennyplane – eventually evolved into the MQ-1 Predator drone.

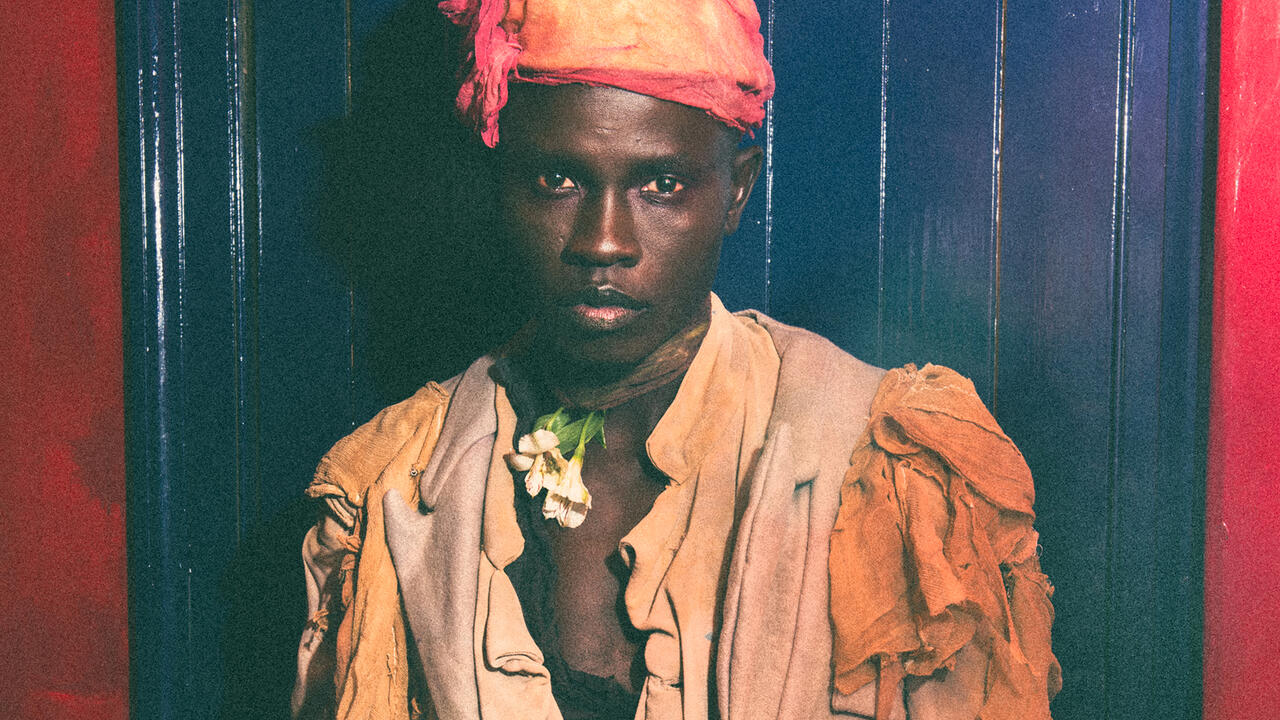

Our photographic record of that unlikely convergence recalls the pin-up subgenre of aircraft nose art: military aviation’s graphic admixture of sublimated sex and libidinal violence, transferred onto the fuselages of aircraft. Here, death is displaced by la petite mort. No surprise that nudes and grim reapers were among the most popular iconography; nor that the further planes flew from the dictates of puritan propriety, the racier their adornments became. Some of the most prurient imagery was to be found in the Pacific, with aircraft names frequently projecting the erotic onto the exotic: Pacific Princess, China Doll, Pink Lady, Versatile Lady, Problem Child, Strawberry Bitch, Lilly Virgin and Nightie Mission. Today, Virgin Atlantic’s commercial fleet proudly preserves this chauvinist tradition, with colonial classics such as Indian Princess and African Queen escorting its perkier puns Miss Behavin and Maiden Tokyo.

While female fashion and gender stereotypes were readily co-opted by military nomenclature, this process also played out in reverse. The bikini – Louis Réard’s ‘devastating’ and ‘explosive’ 1946 sartorial sensation, named after the Pacific atoll and test site for its ‘atomic’ appeal – quickly became de rigueur attire for Côte d’Azur ‘bombshells’ such as Brigitte Bardot; while, in the US, sex and violence were seamlessly aligned in that most iconic of accessories: the bullet bra (made famous by Jayne Mansfield and, of course, Monroe herself).

A recurring theme in recent reporting on drones relates to their apparent affront to conventional notions of masculinity. Compared to the fighter-jet fantasies of the Top Gun (1986) generation, the monotony of 12-hour shifts in a Nevada desert cubicle has given rise to nicknames such as ‘chairborne rangers’ for the pilots who fly these lethal robots. Indeed, the desire to preserve the military potency and prowess of unmanned flight was implicit in the codename for the US Army Air Force’s fledgling drone programme: Operation Aphrodite.

Yet, it is perhaps the myth of Actaeon – the huntsman transformed into a stag and devoured by his own dogs – which most perfectly mirrors this tale. For, while the Dennyplane was designed as a practice target for army artillerymen, today’s remotely piloted vehicles now do the targeting. Above the skies of Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Yemen, it is the hunted who have become the hunters.