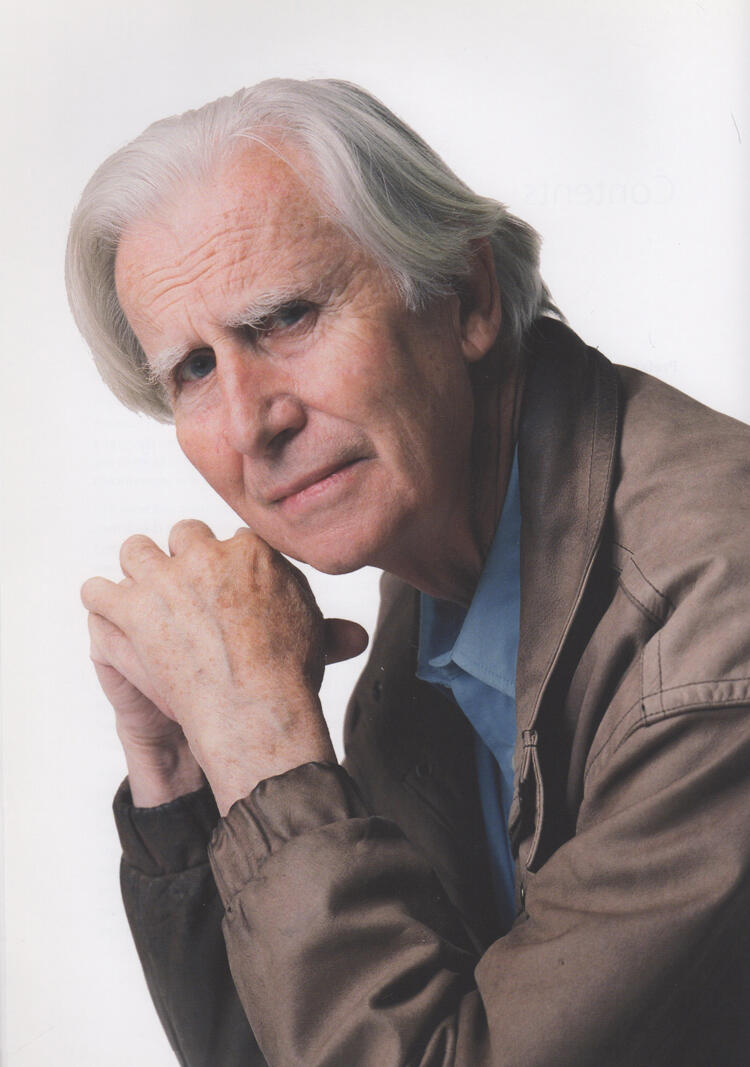

The Many Lives of Brian O’Doherty (1928–2022)

Alexander Provan pays tribute to the polymathic artist, critic, novelist and television presenter and his alter egos

Alexander Provan pays tribute to the polymathic artist, critic, novelist and television presenter and his alter egos

Brian O’Doherty had the pleasure of dying and being reborn many times, and I’d be remiss in treating him as someone with a single life (or afterlife). An obituary – an imposition of coherence – seems ill-suited for an artist who, from his birth in conflict-ridden Ireland in 1928 until his death in New York this month, understood himself as divided, and channelled the fractured identity he inherited into pseudonymous personas of his own invention. As an artist as well as a critic, editor, novelist and television presenter, O’Doherty reckoned with the weight of history while advocating for art as a vehicle to pursue independence in thought and expression, governance and self-definition.

Though the circumstances of O’Doherty’s childhood in the shadow of British imperialism prompted a lifelong struggle to balance his ancestry and his desire for autonomy, he remained himself until he was 43. After becoming a doctor in Dublin, he moved to Boston in 1957, then gave up medicine for art, working as the writer and host of Invitation to Art, a local public television show. He ended up marrying his predecessor, the art historian Barbara Novak, and decamping for New York, where he joined The New York Times as an art critic and found a place in the city’s artistic milieu, exhibiting grid-like drawings and scripts for a series of Structural Plays (1967–70) that translated the ontological questions of conceptualism into an ancient Celtic alphabet called Ogham. Then, in 1972, following the killing of 14 unarmed Irish civilians by the British army on what became known as ‘Bloody Sunday’, O’Doherty disavowed his identity and assumed the unambiguously symbolic name of Patrick Ireland, which he pledged to keep until the British withdrew troops from Northern Ireland.

Eventually, Ireland’s artistic career overshadowed that of his progenitor. He became known for geometrical drawings and sculptures resembling chess boards and mazes, as well as ‘Rope Drawings’ (1973–c. 2018) that transform galleries into three-dimensional canvases via nylon cords stretched across monochromatic walls. Meanwhile, O’Doherty focused on writing and broadcasting, showing a remarkable talent for inhabiting the media that he was scrutinizing. In 1976, he published ‘Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space’, a series of paradigm-busting essays in Artforum on the commodification of art – and a call to arms for artists – that soon became canonical. And, increasingly, he set aside the formal obliqueness and rarefied audience of the avant-garde in favour of homilies on art and architecture for NBC’s Today show and plot-driven novels on historical figures with fluid or fabricated identities, such as the Booker Prize-nominated The Deposition of Father McGreevy (1999). Even as O’Doherty’s own name became more and more elastic, he came up with three additional alter egos – Sigmund Bode, Mary Josephson and William Maginn – to speak and stand in for him. Finally, in 2008, O’Doherty recognized the evacuation of British troops by burying an effigy of Patrick Ireland at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin, presiding over the ceremonial return of the artist to his own body.

I met O’Doherty four years after this rebirth, at the cavernous, unfussy Upper West Side apartment and studio that he shared with Novak. He was surprisingly jovial, given that he had recently been hospitalized in Germany due to a medical emergency and nearly died: after flatlining, he felt himself leaving his body, an experience that he described as uncanny but familiar: ‘another death without a death’. My excuse for visiting was that I had co-founded a magazine, Triple Canopy, which was animated by the idea of the internet as an alternative to the gallery, and was indebted to O’Doherty’s argument about the white cube constraining thoughts, expressions and interactions. I had also been inspired by the 1967 issue of Aspen – a short-lived ‘magazine in a box’ – that O’Doherty edited and designed, with a ridiculous roster of contributors: Roland Barthes, Samuel Beckett, John Cage, Marcel Duchamp, Susan Sontag, et al. Packaged, ironically, in a pristine white box, the issue includes essays, scores, Super-8 films, flexi-discs with recordings of music and prose, and modular artworks to be constructed from pieces of cardboard and transparencies.

O’Doherty guided me through clusters of books, artifacts, artworks and documents that marked the vast, various terrain of his existence, discoursing on Celtic glyphs and recalling confabs with Duchamp. He showed me beguiling portraits of himself in the plural – photos of his alter egos, mirrored busts, death masks – and of Duchamp, whose electrocardiogram he took in 1966 and turned into an homage by way of appropriation. I had expected our meeting to sharpen the sketch I had put together through anecdotes, internet searches and the fraction of his work that I had consciously absorbed. But O’Doherty spoke less of himself than of an assembly of characters born from a single body, each with a particular role, style and backstory. He was frail and uncertain about his recovery, but left me with the impression that he was also buoyed by the prospect of his creations living on without him, achieving independence.

When I first met O’Doherty, his influence seemed to have eclipsed his presence as an artist, perhaps because he rejected the currency of his name in favor of cultivating familial bodies of work. Under the reign of surveillance capitalism and social media, though, O’Doherty’s position came to seem prescient, relatable, even exemplary, and he found himself transformed into a ‘saint’ – a subject of veneration, often in the form of exhibitions, essays, interviews, and monographs – which left him equally grateful and amused. Though I only saw O’Doherty occasionally after our meeting, I came to know him as I know no one else, through the conjunction of conversations with an entirely distinctive character – disarmingly genial, chronically witty, dauntingly erudite, bracingly opinionated, anachronistically chivalrous – and an immersion in the artifices that propagated his personality while refracting his person. After hearing about O’Doherty’s death, I pulled up a 1990 clip of him as a television critic reviewing Patrick Ireland, speaking about a human-scale labyrinth recently realized by the artist. He describes the experience of traversing the sculpture in the agreeable, noncommittal voice of a network host: ‘You exit as easily as you enter, changed or unchanged.’ Then he grins, adopts a pretentious tone, and addresses Ireland as if he were a historic figure, as if he and his art were as intriguing and unknowable as ancient ruins. ‘What kind of consciousness is retrievable from these artifacts? A fictive person, perhaps, too smart to be an artist, too dumb to be anything else.’

Main image: Brian O’Doherty in his studio in Manhattan, 2006