Buffer Zone

The City of London’s annual sculpture park reveals the complex interplay between global corporations, urban space and ‘the public’

The City of London’s annual sculpture park reveals the complex interplay between global corporations, urban space and ‘the public’

Among myriad possible definitions, ‘the public’ is always a setting where private domains meet and interact, where private interests clash and negotiate with one another through the institutions of political life, the media, claims over public space, and, indeed, commerce. Though commerce and the public (space, good, realm, and so on) are often portrayed as ideological enemies, the former is very often the entry point into the latter.

The fabled Roman forum, still the Holy Grail for planners tasked with creating vibrant public places, was a place of trade as much as gossip and social encounter. The squares of southern European cities, also often paradigms for new public space development, are ringed by cafés and regularly occupied by markets. The Viennese coffee house – the ultimate emblem of the public realm as a site for political engagement and debate – was no different in business terms from a café today. The dominant notion of urban vitality is a streetscape populated by lively commercial exchange, and it is through participating in this exchange that we find ways to share the public realm with others.

‘Sculpture in the City’, the annual public art project of the City of London which seeks to transform the Square Mile into a sculpture park each summer (now in its seventh edition), evokes this genealogy: what do we mean when we speak of ‘the public’ in the ultimate financialized space, and what kind of work are art objects doing in this space?

In the past few years, the phenomenon of privately-owned public space (Pops) has been critiqued as a threat to a democratically just and inclusive city. In her book Ground Control: fear and happiness in the twenty-first century city (2012), journalist and academic Anna Minton has argued that they are eroding the social fabric of society, warning that ‘the real problem is that because these places are not for everyone, spending too much time in them means people become unaccustomed to – and eventually very frightened of – difference’. Indeed, Pops are concentrated in and at the fringes of the City of London, as demonstrated by a recent Guardian investigation, with focal spaces such as Broadgate and Paternoster Square being owned and managed by private estates, excluding undesirable uses and users. Nevertheless, it is worth trying to think beyond this criticism to ask questions about the relationship between private domains, commerce, and the urban public realm.

Of course, the highly managed Pops of the City of London are not the same as the municipal squares and everyday streets of London’s town centres, populated by community events and local interaction. Nor are they Trafalgar Square, the iconic focal point of protest and demonstrative politics in the city. There is an uneven geography of what constitutes the public across London, but there is also a complex interplay between the spatial economics of ownership, law and interests in any given place.

The façades of buildings, for example, are privately owned but they are the backdrop in front of which the theatre of public life plays out. The façade is also the face with which a private space performs to the public, and in doing so it has to adhere to public planning law constraining its aesthetic relationship to its surroundings. Art itself is the rendering of the subjectivity of the artist into object form, and by bringing it into common view, we allow their private interiority to become a feature of public life, acting as a material held in common between strangers. Rather than imagine an oppositional relationship between public and private – in which, for example, state-owned space automatically has the ideological upper hand over that which is private – we need a more nuanced appreciation of the dialogue in play.

The way art is commissioned and placed in public can reveal some of these dynamics. The history of public art can even be read as a history of legal and economic control over the city. Monuments depicting royal figures and colonial aggressors, such as Nelson and the Duke of York, were sited to dominate ceremonial squares from atop high columns and reproduce monarchical power by communicating a dominant history to the masses. After the Second World War, rather than creating standalone objects, surfaces of tower blocks and underpasses were treated creatively by artists placed within local authorities such as the London County Council, in an attempt to centralize and rationalize the aesthetics of the city during the height of modernist planning. Many stunning reliefs by William Mitchell, design consultant for the LCC from 1957 to 1965, are built into the walls of estates across London – but they do not become monuments, fading instead into the background of everyday life, and indeed rarely being known by name.

‘Sculpture in the City’ reveals another dynamic – that informing the relationship between global corporations and urban space. Corporate facades, instead of communicating organizational identities through ornament, often use glass to create a curious mirroring that reflects the public back to itself, making buildings all the more opaque in doing so. Nathaniel Rackowe’s Black Shed Expanded (2014/2016) uses this effect, consciously or otherwise, to project an image of itself across the foyer of 6 Bevis Marks. Meanwhile, the investment companies that own the building have only a symbolic presence in the material space, operating almost entirely as a network of economic and informational flows that cannot be tied to a single location.

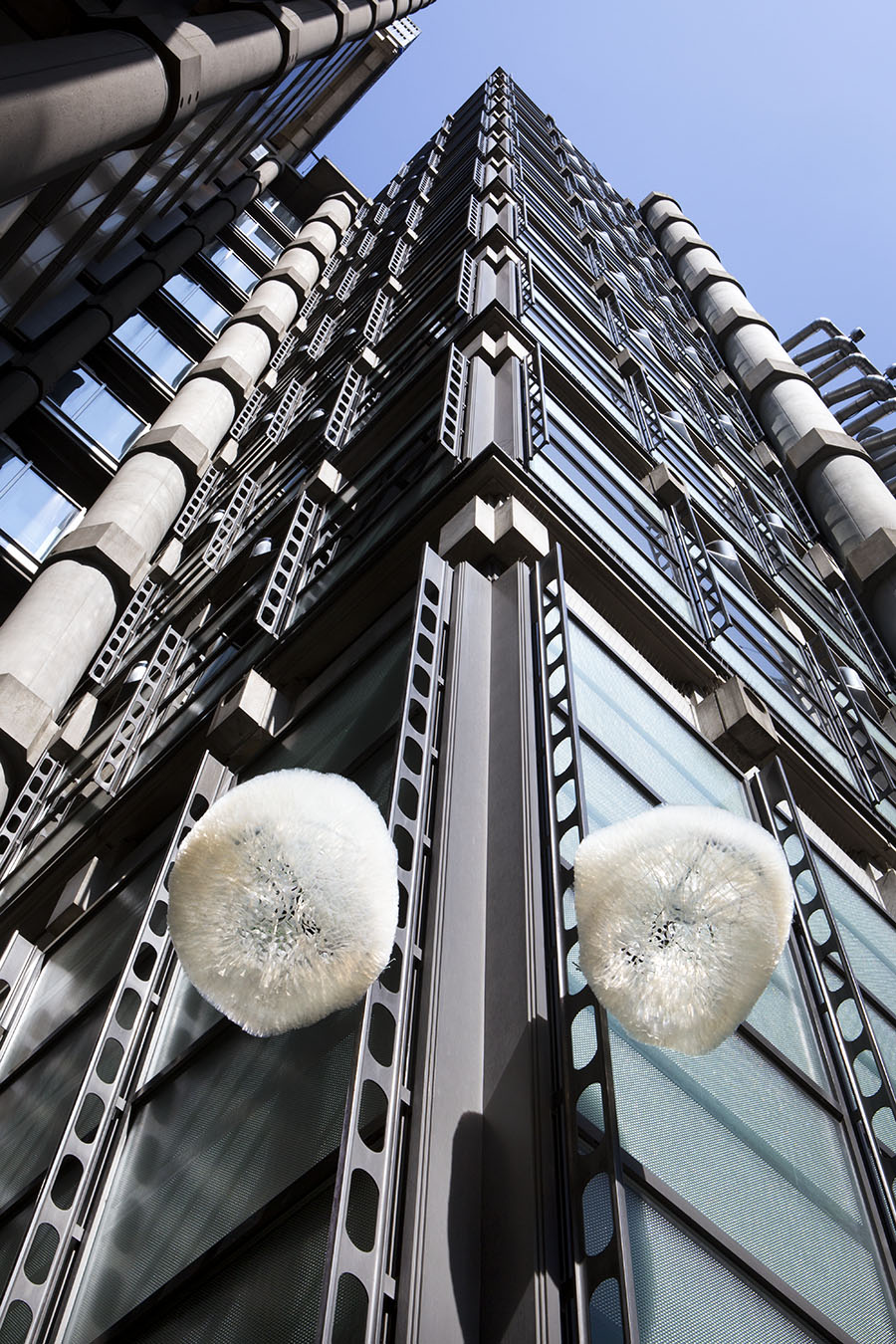

Nonetheless, the ‘Sculpture in the City’ project represents a willingness on behalf of its corporate partners to seep out of these towers: to perform to, and therefore to create a public. We suddenly realize that these towers are surrounded by an almost imperceptibly demarcated buffer zone of privately-owned public space, whose boundaries are highlighted when their owners fund sculptures to be placed at their edges. Gary Webb’s playful sculpture Dreamy Bathroom (2014) sits out at the frontier of the space belonging to the Willis Building on Lime Street, turning it into a place of encounter between an audience and the private organizational domain of the building. Kevin Killen’s Tipping Point (2016) neon takes a different approach, being applied to the pillars of the Leadenhall Building’s vast entrance and becoming absorbed into its architecture rather than stepping out into the street.

Read: Brian Dillon on the fate of postwar murals in the UK

Could publicness, then, be a case of how far something is from whom or what ever paid for it: measurable geographically? A sculpture paid for by a company but placed far from its own physical location might be described as public, but provided philanthropically. Nelson’s Column was funded in the 1840s by private investors as far afield as the Tsar of Russia, and has been absorbed into the public imaginary. Another work applied directly to a building might become aesthetically part of the streetscape but would doubtfully be thought of as public in the same way.

By facilitating cooperation between private interests in the staging of a public event, ‘Sculpture in the City’ articulates these buffer zones, where ownership regimes interface with one another, as possibilities for negotiation and cooperation between entities that might otherwise encounter one another only through mediated commercial exchange. The project offers the opportunity to explore and to reflect upon the different ways that privately-owned art can meet the public realm: from Mhairi Vari’s Support for a Cloud (2017) clinging to the side of the Lloyds Building to Martin Creed’s seemingly more autonomous Work No. 2814 (2017) appearing to consist of itinerant plastic bags caught in a tree. Private funds applied to these spaces create the economic possibility for a changing roster of artistic work, which in turn can be more experimental and more challenging than if provided with public funds, often hamstrung both by tight budgets and the responsibility to represent, or appeal to, a democratic mass.

Whilst a stable landmark might have the ability to embed itself into the shared memory of a community and become an anchor in its social life (as evidenced by the fierce debates around the removal of the much-loved Peckham Arch, with its light sculpture by Ron Haselden), ‘Sculpture in the City’ facilitates a different, changing set of relationships that are nonetheless highly public. We should not unquestioningly sanction the way private interests claim and control space in cities. Nonetheless they can and do very actively stimulate public life in ways that should be engaged with positively, if critically.

Main image: Mhairi Vari, Support for a Cloud, 2017, outdoor television aerial, wire coat-hangers, greenhouse/poly-tunnel repair tape, 3 pieces approx 150 x 75 x 65 cm each, installation view 2017. Courtesy: the artist and Domobaal gallery; Photograph: Nick Turpin