Carolee Schneemann

It’s hard to believe that this was Carolee Schneemann’s first solo show in London, even though she lived here for several years in the late 1960s and early ’70s. At that time, her now-mythical status was being established by provocative experimental performances including Meat Joy (1964) and Interior Scroll (1975). With the ‘Water Light/Water Needle’ project (1965–66), Schneemann experimented with a gentler, more romantic register. Her use of bodies to challenge sexual mores was replaced by sensual moments and social interactions; confrontation gave way to collaboration. In many ways, the project also crystallized Schneemann’s engagement with working collectively, which she had explored in Meat Joy and through her involvement with the Judson Dance Theater.

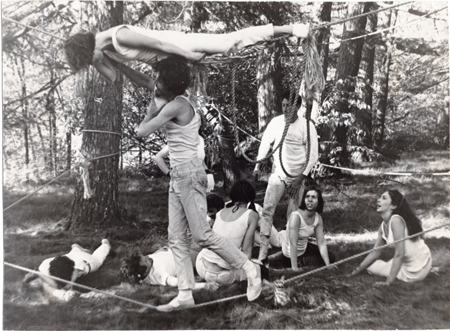

The exhibition was a constellation of unseen work from Schneemann’s ‘Water Light/Water Needle’ series, with Water Light/Water Needle (Lake Mah Wah, NJ) (1966) – a diptych shot on 16mm film – at its centre, surrounded by preparatory drawings, photographs and recently reworked live shots. ‘Water Light/Water Needle’ was a series of performances – ‘kinetic theatre’, to use Schneemann’s terminology – in various locales in 1966. It premièred at St. Marks Church-In-The-Bowery, New York, where Schneemann had installed a system of anchors and pulleys in the walls of the church to string two sets of ropes across the space, a low one and a high one. Performers dressed in white worked their way around the contraption standing on the low rigging and holding onto the high one, relying on each other and the ropes for support. The audience sat on crumpled newspaper directly underneath the performers. Two months later, Schneemann took the performance to the Havemayer Estate in the New Jersey countryside where a cast of musicians and artists restaged it in a bucolic setting.

Schneemann first conceived the work in 1964 in Venice, where she had been invited to visit the Biennale following the succès de scandale of Meat Joy at Jean-Jacques Lebel’s Festival of Free Expression in Paris. Her sketches for the piece, energetic line drawings on cartridge paper that trace the movements of fleshy bodies in the air, capture some of the dynamism of the play of sunlight on water in the Venetian canals. Like these mirrored surfaces, the video is also filled with reflections – double exposures and repeating angular young bodies. Shots of bodies in suspension flow into one another, slipping across the screen with luminous liquidity.

‘Water Light/Water Needle’, which, like Meat Joy, was performed by fellow members of Judson Dance Theater, shared the group’s commitment to exploring ordinary movement through performance, as well as its concerns with how bodies move within specific, defined spaces. In an early scene, the naked gaggle of performers huddles thigh-deep in Lake Mah Wah, forming a cell divided into a row of pale buttocks backlit by the setting sun. A young Meredith Monk – then just 23 – giggles as she waddles to shore with her hands at awkward angles. Schneemann, always gorgeous, clutches her lover, the composer James Tenney, as they lean on ropes that lurch under their weight. It’s an Arcadian scene and the performers look natural in front of the camera, undaunted by the physical demands of the piece. Shots of rope knots, their frayed ends swaying in the breeze, echo a moment when Tenney undoes Schneemann’s hair, which swings down as she hangs over a rope.

But how are we to look at this work, now nearly half a century old? Is it tainted with nostalgia or does its quality lie in the pleasure it makes us feel, as these young actors must have felt it on that beautiful summer’s day? The archival materials included in the exhibition went some way toward tempering the dreaminess of the film. Black and white archival prints contrasted the urban setting of the first performance with the rural idyll of Lake Mah Wah. The Venice diagrams gave an indication of the ambitious mechanics involved in making the rope stucture. A series of newly enlarged photographs taken in St. Mark’s Church, painted with washes and flashes of acrylic colour, offered a scruffier account of the first performance. Ultimately, though, it’s striking how uncontrived these pieces are; they avoid the knowing look that pervades a range of contemporary performances to camera. Within Schneemann’s oeuvre, the work also feels unusual; ‘Water Light/Water Needle’ provides a counterpoint to her more sexually and politically charged works, offering a vision of collectivity and relationships between bodies that are mutually dependent and supportive, equal terms in what looks to be a balanced set of relations.