Catherine Story

In 1952, while he was in Paris promoting his film Limelight, Charlie Chaplin was introduced to Pablo Picasso over dinner. Following a few unsatisfactory exchanges through a translator, the pair resolved to abandon speech entirely, and spent the remainder of the evening happily communicating in mime. With its frequent nods to these two titans of Modernist visual culture, Catherine Story’s exhibition ‘Angeles’ functioned as a reunion of sorts. Drawing on the coterminous evolution of Cubism and cinema, and employing a palette of off-whites and pale terracottas that recalled the blush of Picasso’s ‘Rose Period’ (1904–06) and the sepia tones of silent films, her paintings and sculptures explore the links between two revolutions in representation: the expansion of two dimensions into three in the chilly studio spaces of the Bateau-Lavoir, and the contraction of three dimensions into two on the sunbaked lots of Hollywood.

Hugging the walls of Carl Freedman Gallery, Story’s sculptures were displayed on a series of backless plinths that had the jerrybuilt appearance of a movie prop or backdrop, designed to be seen not by mobile human eyes but through a camera’s locked-on lens. On top of one of these sat Limelight (all works 2011), which took its title from Chaplin’s film and its form from Picasso’s 1919 painting Still Life With Pitcher and Apples. In an affectionate comic jab at the Spanish artist’s immaculate and far-from-humourless neo-neoclassicism, Story remade the canvas’s blemish-free jug in rough cement, poking a navel into its bulging belly, and tweaking its spout into a gurning mouth and the accompanying fruit into a pair of goggling eyes. Not quite a relief, but too flat to really function as a volumetric approximation of a pitcher, it seemed stuck between the pictorial and the sculptural – no wonder it stared and gibbered. Perhaps, though, it was made nervous by the nearby United Artists, two clay and acrylic sculptures of vintage movie cameras that scanned the room from their plinth like a Golden Age precursor to CCTV. Pared down to blocky, cartoonishly Cubist forms, they were the close cousins of the devices depicted in the paintings Angeles (II) and Millionaire. (The latter work is named after a character in Chaplin’s 1931 film City Lights that opens with a scene in which a monumental figurative sculpture is unveiled, and Chaplin’s ‘Little Tramp’ is discovered asleep in its stony arms, as though this cinematic icon were the child of a much older medium.) There is a wonderful airlessness about these images, as though they were born not in a painter’s studio, but inside a cinematographer’s black box. Angeles (II)’s motif was repeated in the small jesmonite sculpture, Star, which was installed high up on the gallery wall. Read right to left, it is clearly a camera; read left to right, it resembles the head of a robot duck. Technology, in Story’s work, is Janus-faced, and always threatens to transform itself. It makes sense, then, that the materials she often turns to – cement, plaster and found wood for her plinths – are those used by early Hollywood set-builders.

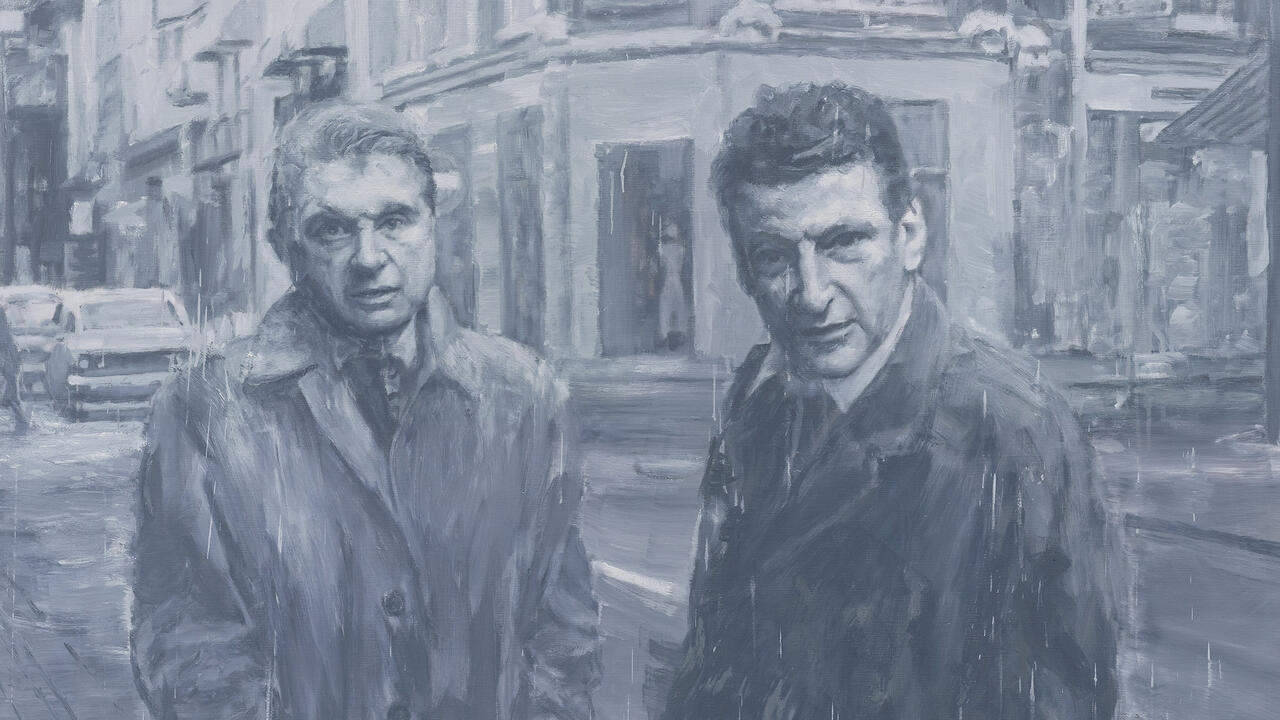

If ‘Angeles’ was about dimensional instability (even its title hints at a higher, heavenly, reality), it was also in part about men. In addition to providing starring roles for notorious womanizers Picasso and Chaplin, the exhibition featured a cameo from Clarke Gable, a man so steeped in testosterone that it was said that when he walked across the MGM lot ‘you could almost hear his balls clank’. The sculpture Gable, though, conjured his broad shoulders from crumbling plaster, and gave him a groin so featureless that it could barely summon a tinkle. Story’s point here wasn’t, I suspect, a straightforward critique of macho Hollywood or art-historical myth-making, but rather a gleeful enjoyment of both its thrilling bombast and its profound silliness. As her witty, beautifully produced show testified, it’s when you understand an illusion as an illusion that the real fun begins.