What Artists Do When They Can’t Sleep

The artworks of Remedios Varo, Louise Bourgeois, Mat Collishaw and Rut Blees Luxemburg offer a portrait of the artists' sleepless nights

The artworks of Remedios Varo, Louise Bourgeois, Mat Collishaw and Rut Blees Luxemburg offer a portrait of the artists' sleepless nights

This article appears in the columns section of frieze 236, based on the theme 'After Dark'

Remedios Varo’s painting Insomnio I (1947) draws a stark portrait of sleeplessness: in an unfurnished house, three pairs of eyes float in a sequence of progressively darker rooms while in the foreground, two insects with crystalline wings drift through the window, drawn towards the fulgent light of a candle. It is the hour when we humans should be asleep and leave others to their creaturely activities; instead, we remain trapped in a liminal, inhospitable realm from which nothing valuable can ever emerge. Varo’s bleak image of insomnia was one of many commissions she carried out for Bayer pharmaceutical company in Mexico; this is an advertisement for sleeping pills.

Yet, for most artists, including Varo herself – whose wide-eyed, ethereal figures often bear the haunted mien of insomniacs – night is both fraught and fecund, a double-edged heightening of the senses that can lead down any number of paths. As a lifelong insomniac, I am all-too-familiar with its ambiguous potential, the contents of my head growing louder and more demanding in order to compensate for the silence beyond.

Insomnia is the ultimate confrontation with the self, where the ‘I’ looms larger than ever. Because of this, it is also an inviting time for doppelgangers, when our suppressed selves might break away, clothe themselves in our fears and declare themselves in all their monstrosity. In a favourite music video from my youth, The Cure’s ‘Lullaby’ (1989), singer Robert Smith lies in bed in striped pyjamas, blanket pulled up to chin. He glances nervously at the clock on the wall, which reads 10:15pm (not terribly late for an insomniac but a nod to the band’s 1979 anthem ‘10:15 Saturday Night’) as an enormous spider crawls up the wall to the march of drumbeats and plucked violins. The clock becomes the spiderweb, the spider’s movements the creep of thought. We see that the spider wears Smith’s face. They have the same enormous, charcoal-ringed eyes and teased-out hair. He is the spider; the spider is he. Immobilized by fear, Smith glances over at his bandmates who stand in a row like tin soldiers or clockwork automata, playing their instruments with jerky movements as they slowly become covered in the spider’s tacky gauze. Everyone, everything, is suffocated by cobwebs until, by the end, Smith’s limbs are indistinguishable from the spider’s, his two selves merging as he vanishes into its furry mouth.

Spiders were central to the art of Louise Bourgeois, inhabiting an important corner of her imagination, yet they aren’t present in any of her 220 ‘Insomnia Drawings’ (1994–95), created during what must have been a particularly maddening spell of sleeplessness. In an interview for the two-volume publication Louise Bourgeois: The Insomnia Drawings (2000), the artist explains how the works acted as a form of lullaby: ‘My drawings are a kind of rocking or stroking, an attempt at finding a kind of peace.’ In these notebooks, Bourgeois draws faces, buildings, flowers, mineral formations, waves, clouds and musical notes as well as more abstract compositions – spirals, mazes, loops, dots, coils and concentric designs – in which one can detect the hand gestures of an exasperated mind. In scratchy red ink, she pens notes to herself or her neighbours, draws dips and peaks that resemble an echocardiogram or bales of hay awaiting the pitchfork of clarity. Orphaned objects and figures, adrift in febrile landscapes and interiors, yield strange tapestries. The sketches feel like loose ends and threads, a renegade energy that hasn’t made it into her sculptures, where matter is harnessed and condensed. These notebooks are a factory of nocturnal energy, spiralling out in all directions, contained yet uncontainable. Many of the drawings have a spidery line, concentric circles like webs spun by a sleepless mind forever tangled in its own loops.

Night may be the domain of idées fixes, but it’s also a time of spiders and bats, ambiguous muses that nest in almost every culture’s lore and mythology, their symbolism more tangible as darkness gathers. They may evoke vigilance and protection and nocturnal industry, or embody anxieties we’ve tried to keep at bay, taking shape at the very moment when we ourselves feel most disembodied. Along with spiders and their miniaturist introversion, it’s the winged freedom of bats I’m most drawn to, and their almost sylphlike way of evading all obstacles without interrupting movement.

Mat Collishaw’s three-panelled video installation Echolocation (2021) depicts a bat’s nocturnal perambulations as it flies over ghostly trees and through the spectral chapel of All Saints Church in Kingston upon Thames, the ancient coronation site of various Saxon kings. We experience the landscape from the bat’s elevated perspective, as well as through X-ray vision that makes the creature as transparent as the chapel’s gothic interior, forlorn statues and vacant chairs. A tremendous sense of longing accompanies the bat’s powerful wingbeats, which carry it through the translucid and sepulchral world below, shorn of its familiar external layers. The work opens with the voice of one mournful cello, gradually joined by a choir, strings, tribal drums and bat sounds – an elegiac habitation of night that builds into a more communal one as the bat multiplies, then shrinks again to a single note as it flies off at the end, leaving us with the skeleton of the church, a ghostly ruin, the shell of our ruminations. Collishaw has mentioned his desire to address lost moments of British history and the ways in which places are stalked by a weird and all-but-forgotten ancestry, but, for me, the piece is also an evocation of the wakeful mind at night: its flight, its poetry, its way of collapsing time, a moving tableau of insomnia. When we gaze into the night sky, we are also looking back, receiving the light from distant objects.

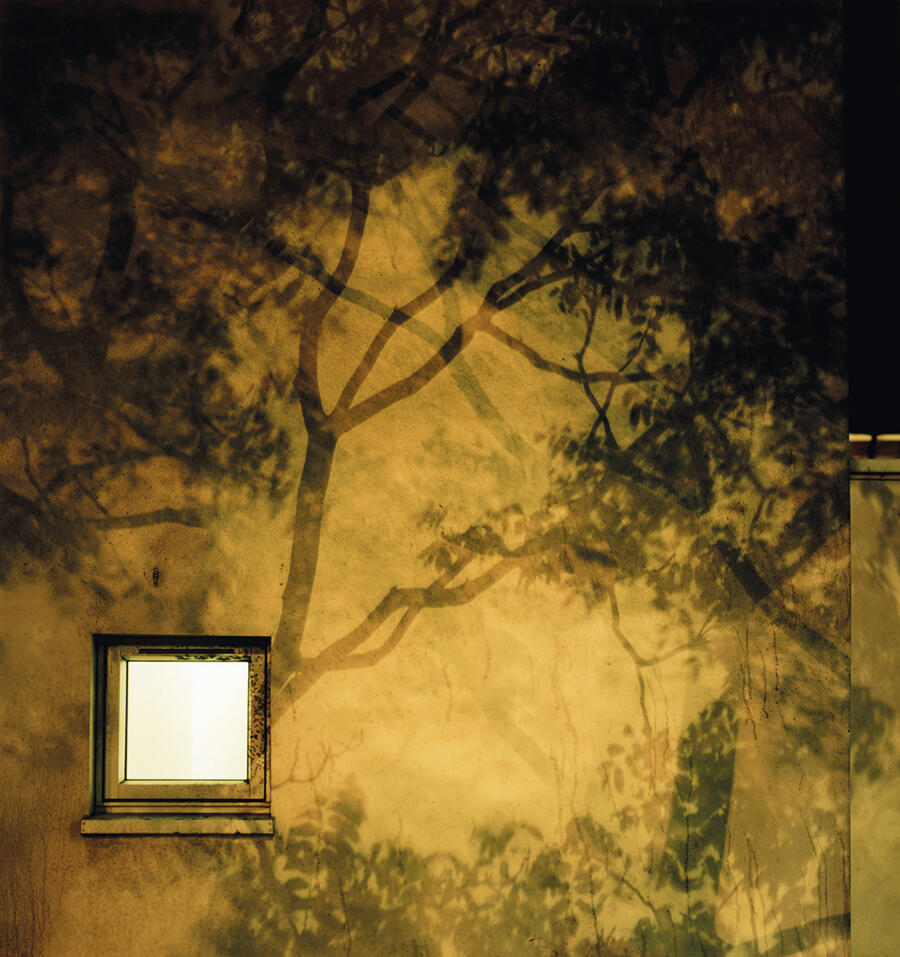

Rut Blees Luxemburg offers an equally romanticized portrait of night: in her case, a poetry of estrangement in photographic cityscapes, mainly of London. If the industrialization of light in the 19th century led to a disenchanted night, as Wolfgang Schivelbusch writes in his eponymous 1988 book, then Blees Luxemburg makes it again mysterious. With her distinctive palette of burnished gold and ochres, she catches shuttered businesses, corner shops, beauty salons, car parks and high-rises. Human activity is dormant, silenced by night, as another language emerges. The glowing effects are achieved through long exposure times; out in the city, the insomniac becomes an involuntary nightwatchman. In one photograph, Versuch der Betörung/Attempt of Seduction (1999), a square window stares out from a darkened ochre wall, its surface scrawled by the shadows of tree branches like a Japanese silkscreen. Here, two kinds of consciousness meet: the window, a lit mind; the wall, a fantastical play of patterns.

We may think of insomnia as an act of resistance – a turning down of sleep, that human sustenance free to all. We don’t partake in what most others happily do: we are kept up by an uncategorizable hunger, unsatiated, treading a line between the impossibility of sleep and the refusal of it, caught in mental loops or ghostly flights in which the world is echoed back to us at a higher frequency. Our wakefulness becomes a state of longing, when everything that seems unattainable is enveloped in, or merges with, the desire for the sleep that eludes us. What do we do with this X-ray vision, with our squares and circles and odd geometries? We welcome our own bats and spiders and try to make the most of our state of hypervigilance, in the hope of arriving at a space where our physical and metaphysical nights might coexist.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 236 with the headline ‘Sleepless Nights’

Chloe Aridjis's writing will be included in Paula Rego: Crivelli’s Garden, set to be published by National Gallery Company Ltd on 25 July

Main image: Rut Blees Luxemburg, Versuch der Betörung/Attempt of Seduction, 1999. Courtesy: © Rut Blees Luxemburg and DACS