Colter Jacobsen

In the context of group exhibitions Colter Jacobsen’s work can seem inscrutable, his found-object collections and enigmatic drawings offering evidence of a restless, but merely personal logic. His recent solo exhibition at Jack Hanley Gallery revealed a somewhat more systematic set of investigations, based on imperfect pairs, correspondences and symmetries – as though Jacobsen had extrapolated an entire art practice from Robert Rauschenberg’s Factum I and II (1957) and Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ Perfect Lovers (1987–90). Indeed Jacobsen’s title for a pair of ‘found twin paintings’ marks his debt to Gonzalez-Torres’ work explicitly: they’re called mi (perfect lovers) me (2007).

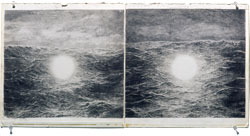

This work, like many in the show, is produced as a kind of encounter with another artist. Often this collaboration is mediated by a thrift store or rubbish skip. The two ephebes in mi (perfect lovers) me were painted by someone named either ‘Igmer’ or ‘Iymer’, while another pair of thrift store paintings (still sporting their price tags) is attributed to ‘Guy Cri’. A great and enigmatic photograph by Donal Mosher, a mysterious light emanating from a rough seascape (Untitled, 2004), is echoed by two of Jacobsen’s drawings across the room (flash falls (after Donal), 2007). Included among Jacobsen’s work, these objects speak of the artist’s affinity for an attentive, responsive form of making, as well as the importance of real and imagined social relationships to his practice.

Filling the back wall and floor was a large accumulation of found materials: cut-outs from corrugated cardboard shipping containers organized on the wall, and a mound of foil wrappers and metallic toys (on the STreet a dream (missing the mint), 2007). A banana printed on the side of a cardboard box is subtitled ‘Enchanted’ and placed next to a gawking, inverted trout; an image of King Kong, borrowed into an box design for Marin Worldwide Moving, rages just below, as giggling yams look on. In this consumer detritus Jacobsen discovers a funny sort of commercial mythopoeia that extends into several other works. ‘Found’ insignia are subtly sewn into narratives elsewhere in the exhibition: the fish might inhabit bridal veil falls (2007) or swim beneath the surface of ‘Guy Cri’s’ lake; a printed commercial logo of a galleon reappears in a ‘found’ seascape across the room (It will disappear with me, 2007).

Dozens of Jacobsen’s meticulous, naturalistic pencil drawings and watercolour paintings pepper the show. Drawing on his collection of found snapshots, each picture is made twice. First he creates an exact rendering of this anonymous photograph; then he renders it again, as exactly as he can, from his memory of the original. Into these mundane scenes – a girl at a dinner table proudly holds up her new dress (11 years! (a quight around the sun or new camo into adulthood), 2007), a woman in her suburban living-room takes dissolute rips off her bong (high light, 2007) – appear curious discrepancies. The girl’s smiling face changes shape, and the pattern of her dress alters; the stoner keeps her hair-style and T-shirt, but the room around her realigns imperceptibly. The differences between the various renderings, as Jacobsen says, corresponds to how ‘the dream of memory gets watered down and changes’.

Another watercolour diptych, titled Dura Life (long life) (2007), attends to the multiple inscriptions on the back of a photograph, including date stamps and corporate logos. Discarded and forgotten by their original owners, divorced from the ‘reality’ registered on their flip side, these inscriptions point obstinately to their status as objects of commerce.

The watercolour diptychs were the most conceptually rich works in the show; a set of 20 drawings made in collaboration with the San Francisco poet and author Bill Berkson offered mixed results. Berkson contributed a sequence of typescript paragraphs and stray phrases he’d borrowed from a ‘juvenile detective novel’ in 1980, while Jacobsen filled the pages with drawings. Jacobsen’s response evoked a sort of generic, rustic Americana: a couple with a picket sign poses in front of a clapboard truck; a man shades his eyes as he stares into some hilly wilderness. It was hard to square this imagery with the rest of the exhibition. Still, several of Berkson’s ‘stray phrases’ were given pictures that buzzed with a unique, almost adolescent sexual energy. ‘He jumped up, plucked a blade of grass, and blew a tremendous fanfare’, writes Berkson, as a shirtless worker presses the plunger to trigger an explosion. A pair of disposable plastic lighters was balanced on the gallery’s skirting board just below – like a sexual dyad, this pair seems just about to catch fire.