Critic’s Guide: Glasgow

The frieze digital editors select their highlights from the recently opened Glasgow International Festival

The frieze digital editors select their highlights from the recently opened Glasgow International Festival

Tamara Henderson, ‘Seasons End’

The Mitchell Library

8 – 25 Apr

To walk amongst Tamara Henderson’s mannequin-like sculptures is to discover the relics of a forgotten pagan cult. Trinkets are sewn into ceremonial robes; stems of dried plants are bound into cornucopias; assemblages of bric-a-brac are balanced precariously on ledges or stored in pouches for future use.

Emblazoned with moons, oversized leaves and silken eyes, the tunics of these broad-shouldered beasts celebrate the harvest, the climate and the phases of the moon. They could easily be the loyal subjects of the two totemic figures positioned at either end of the space: Garden Photographer Scarecrow, a goofy, patchwork wicker man, and Body Fountain Fetch, a reclining, coral blue figure whose head is coiled by clear, water-filled tubes (both works 2016). But perhaps we’ll never know the secrets of this patchwork troupe. They could well be lost forever, swirling in the depths of the artist’s mind.

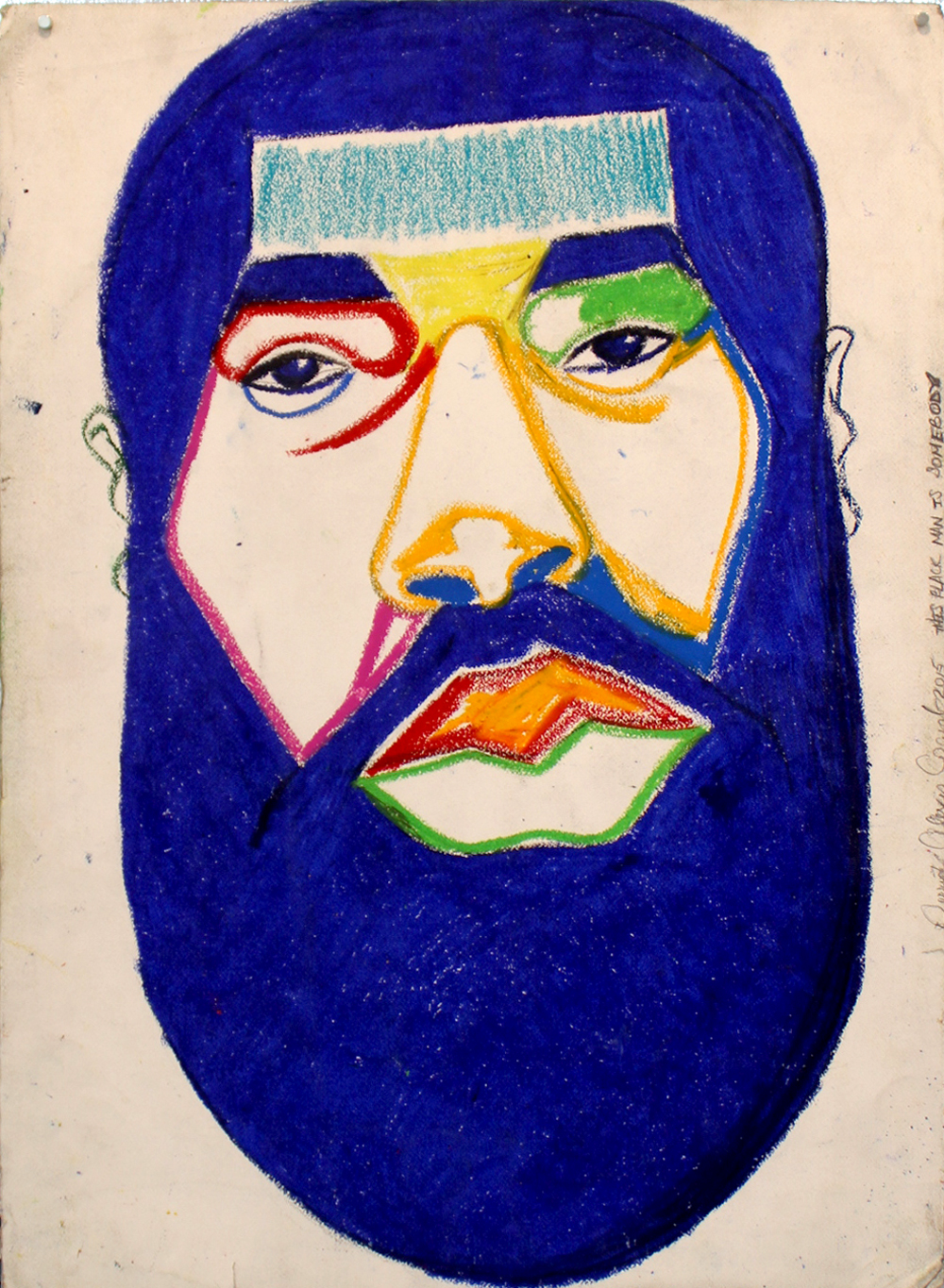

Derrick Alexis Coard

Project Ability, Trongate 103

09 Apr – 21 May

Project Ability is a Glasgow-based artistic organization that provides opportunities for those living with disabilities and mental health issues. Their current exhibition, curated by Matthew Higgs, director of White Columns, New York, features the work of Derrick Alexis Coard, a Brooklyn-born artist living with schizoaffective disorder.

Since his adolescence, Coard has produced images of fictional, bearded African-American males. For him, these portraits are ‘a testimonial that black men can be seen in a more positive, righteous light’. While the works vary compositionally – some men frontward facing and multi-coloured, some positioned within sunny parks, some rendered in heavy, angular graphite echoing early cubist portraits – there is a solidarity amongst the figures, one that is conjured by both Coard’s determined, heavy line-work and the resolute, proud expressions on the faces of each imaginary sitter.

Helen Johnson, ‘Barron Field’

37 Kelvin Hall

8 – 25 Apr

It’s remarkable how well Australian artist Helen Johnson’s paintings hang together, considering their sprawling subject matter. In ‘Barron Field’ alone there are paragraphs of scrawled text, the jovial mouths of emojis and a reproduction of Guido Reni’s The Rape of Europa (1639). It is, however, apt, as Johnson’s works are palimpsests; amalgams of different times and cultures that demonstrate the reverberations of colonialism and the misrepresentations that obscure them.

‘Barron Field’ takes its lead from the 1901 Glasgow International Exhibition, which opened in the same year that Australia began its struggle for independence and presented the spoils of colonisation as curious treasures. Johnson channels/challenges this authored misdirection: while in one work she might curl the gawking smiles of Apple’s emoji army, in another she will reproduce Julian Ashton’s 1889 painting The Prospector, which depicts an empty-handed figure in the midst of a gold rush in colonial Victoria. On the reverse side of one of the paintings, a text reads: ‘A house on rotting stumps’.

Pilvi Takala

Centre for Contemporary Art

8 Apr – 15 May

Finnish artist Pilvi Takala’s videos take place beyond the jurisdiction of the art world. Often casting herself as protagonist, Takala enters into mundane, conventional social environments with a hidden camera, an intruder set on revealing the illogicality of accepted social protocols and enforced rules.

In Real Snow White (2009), the artist is evicted from Disneyland for wearing a costume that is ‘too real’; in The Trainee (2008), she undertakes a month-long traineeship, thinking as opposed to ‘working’ to the bemusement of her colleagues; and in the two-part installation Broad Sense (2011), eight T-shirts are printed with emails from the headquarters of various EU member states noting their various dress codes. The requirements are far from standardized, an indication of the randomness upon which formal, seemingly formulated institutions can be constructed.

Louis Michel Eilshemius, 'E(i)lshem(i)us'

42 Carlton Place

7 Apr – 15 May

Louis Michel Eilshemius (1864–1941) was a painter, maverick, mystic and blowhard. A self-proclaimed polymath, he was known to attend openings in his native New York and loudly criticize the work on view. But this show – curated in the home of artist couple Carol Rhodes and Merlin James – reveals more to him than just eccentric posturing. A collection of 17 miniatures bears out a delicate sensibility: from examples of painful, naif introspection (dusky woodland settings) to moments of daring levity (unnervingly smiling nymphs). Brushstrokes are tender and wild and often in the same picture. Championed by Duchamp – who discovered him in New York in 1917 and who showed him twice at Société Anonyme, the space he co-ran with Katherine Dreier and Man Ray – Eilshemius’s pictures provide a fascinating insight into a complex and distinctive mind.

Andy Holden, 'Laws of Motion in a Cartoon Landscape (II)'

Hanson Street Project Space, Wasp Studios

8 Apr – 25 Apr

An hour-long academic treatise on cartoons shouldn’t be fun, but that’s exactly what this is. Examining the ways in which laws of motion are violated in classic cartoons, this two-channel film sees an animated avatar of the artist present examples of impossible locomotion in a variety of clips, from Bugs Bunny and Road Runner to Tom and Jerry and others. What emerges is a jumble of art history, science, critical and cultural theory and musings that comes across as oddly coherent – just as its subject matter does to children.

Monika Sosnowka

The Modern Institute

8 Apr – 21 May

Distilling architectural form into sculptural content has been an ongoing concern for Polish artist Monika Sosnowska, and in The Modern Institute’s second space at 3 Aird's Lane, a monumental tangle of black steel fills an otherwise bare room. The smell of its spray-painted coat betrays it as new, but the form is actually based on the steel framework of the Osiedle Słowackiego estate in Lubin, Poland, designed in the early 1960s by Oskar Hansen, an architect and artist whose credo of ‘Open Form’ architecture – spatial structure formed by human interaction – found fertile ground in the post-Communist modernism of Poland. Outside the gallery on a grass verge, green twisting structures based on the estate’s playground slouch as if loaded by the weight of their own history.

Alisa Baremboym and Liz Magor, ‘You Be Frank and I’ll Be Earnest’

Glasgow Sculpture Studios

8 Apr – 4 Jun

Made in situ as part of a residency prior to the exhibition, ‘You Be Frank and I’ll Be Earnest’ unites two sculptors who, while geographically and generationally distinct, create work that is surprisingly aligned. Working since the 1970s, Canadian artist Liz Magor casts moulds from impoverished materials – here, beaten up cardboard – and then tags on hair, wool and plastic to create curiously satisfying assemblages. The work of Alisa Baremboym (born in Moscow in 1982) sports a more hi-res aesthetic, but pays similar attention to principles of texture: perforated steel, liquid vinyl and silica gel create cyborg-esque mechanized bodies that seem loaded with digital potential.