Critic’s Guide: Rotterdam

Following this year's edition of Art Rotterdam, Laurie Cluitmans rounds-up the best shows in the city

Following this year's edition of Art Rotterdam, Laurie Cluitmans rounds-up the best shows in the city

Eric Baudelaire

Witte de With

27 January – 27 May

Central to ‘The Music of Ramón Raquello and his Orchestra’, Eric Baudelaire’s solo exhibition at Witte de With, is his latest film Also Known as Jihadi (2017), which follows the journey and eventual court case of a young man, a native of Val-de-Marne, just south of Paris, who decided to join Islamic State. Throughout, road trip-like sequences are intermingled with official reports and investigations into the protagonist’s background. A psychological report speaks of a man with Algerian roots, who grew up in Balzac public housing, attended Yves Klein middle school, and later the Lycée Mallarmé. Those names, iconic of French culture, resound, as the contrast between the cinematic landscape imagery and accompanying legal documents intensifies. This film, set alongside an extensive exhibition of research material and work made throughout the last decade, subtly exposes the complexities of radicalization and violence, as Baudelaire shows the personal to be inextricably intertwined with the political, and generates a surprising sympathy for the radical.

‘Dolf Henkes Award 2016: Daan Botlek, Rana Hamadeh, Rory Pilgrim, Katrina Zdjelar’

TENT

15 December 2016 – 19 February 2017

Downstairs from Witte de With, Rory Pilgrim has covered the windows of TENT with pink newspaper bearing upbeat slogans such as ‘Affection is the best Protection’. It’s emblematic of his soft activism, which attempts to restore the value of words like ‘love’ and ‘hope’, and return to a time before they were emptied of their political promise. Pilgrim’s work is shown here alongside the work of the four other nominees for the Dolf Henkes Award for Rotterdam-based artists: Daan Botlek, Rana Hamadeh and Katrina Zdjelar, who won this edition of the prize for her new film AAA (Mein Herz) (2016), a single-take of a woman singing four different compositions as one. The singer maintains the style, tempo and rhythm of the original music (which ranges from German opera to pop), but her face betrays her struggle to bring together the odd combination of songs. Each time she catches her breath, she draws you into her balancing act, her voice becoming a manifestation of the fragmentation that occurs when switching between social and cultural codes.

Daan van Golden

Museum Boijmans van Beuningen

17 January – 19 February

After Daan van Golden passed away on January 9th, the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen put together a small and delicate display on the life and work of this Schiedam-based artist, who deserves wider recognition outside of the Netherlands. Following a journey to Japan in the early 1960s, Van Golden was exposed to the Zen Buddhist principles of precision and concentration, which he then began to apply to paintings of the geometric patterns found on handkerchiefs, dishcloths and wrapping paper. Though hardly comprehensive and obviously assembled in an unwelcome rush, this temporary staging from the museum’s extensive collection of Van Golden’s work illustrates the enormous diversity of the late artist’s practice. Intimate and loving, meditative and diverse, the works present a marked contrast to the macho steel structures of Richard Serra, permanently on display in the gallery. But despite the shortcomings of this presentation, it is a welcome tribute to one of the most consistent artistic voices in recent Dutch art history.

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster

Sonneveld House

13 November 2016 – 5 March 2017

In 1933, Albertus Sonneveld, director of the Van Nelle Factory, moved into the Sonneveld House, now a famous icon of Nieuwe Bouwen, the Dutch version of the International Style. Commissioned by Sonneveld, it was customized to fit his desire for a modern lifestyle, unlike the stately, but dark, nineteenth-century town house he had been living in. It is this idea of a fresh start that Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster explores in Opera-House Libretto (2016), a selection of film and opera music from the 1930s through to the ‘50s that now plays through the house’s original sound system. Narrative and characters gradually emerge in the passage from room to room: the airy excitement of a new life in Blue and Yellow’s Studio; a sense of homesickness in the German Maids’ Room; and in the living room, a personal drama plays out over Francis Poulenc’s La Voix Humaine (The Human Voice, 1956). Through a delicate and precisely orchestrated intervention, Gonzalez-Foerster suggests a life that the former residents might have lived. She performs a séance, while raising subtle comments on both their time and ours.

Rafaël Rozendaal

Het Nieuwe Instituut

27 January – 25 June

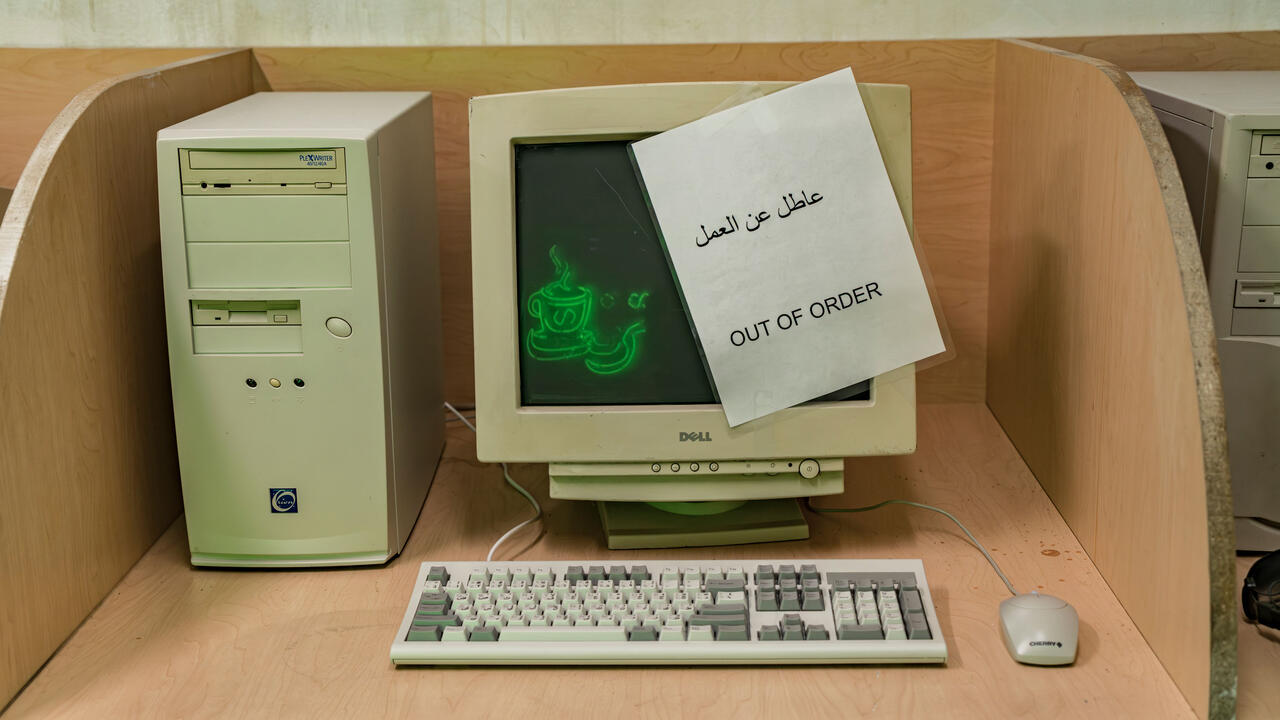

Next door to Sonneveld House at Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rafaël Rozendaal’s installation Sleep Mode: The Art of the Screensaver (2017) pays homage to a remnant of computing history no longer commonly in use. First conceived in the mid-1980s, screensavers were designed to appear onscreen when it wasn’t in use in order to prevent static pixels from burning into a computer’s display. Rozendaal has long been fascinated by these computer generated images and graphics. Focusing on their earliest forms, he brings together seventeen examples, from animations of rain falling or balls bouncing, to endlessly mutating labyrinths and flying toasters. This is what the future must have looked like not so long ago. ‘Mondrian (After Dark 1.0)’, designed in 1989 and included in Sleep Mode …, reveals the rapid development of CGI: whereas Mondrian strove for ever increasing abstraction, CGI pursued ever more realistic imagery. The installation itself is a time capsule that conjures the excitement of the early computer days.

Lotte Reimann

A Tale of a Tub

9 February – 26 February 2017

‘Temptation of Dr. De Clérambault’, Lotte Reimann’s exhibition at non-profit A Tale of a Tub, was commissioned by the C.o.C.A. (Collectors of Contemporary Art) award, which she won last year. Displayed in the atmospheric basement of the former bathhouse of the Justus van Effen-complex – a revolutionary social housing project built in 1922 – Reimann’s photographs and documentary clippings present a central historic character, Dr. De Clérambault, a French pathological psychiatrist who obsessively documented the traditional clothing of Moroccan women. A small selection drawn from Clérambault’s archive reveals an ever expanding associative gathering of images: from screengrabs of advertisements for burqas on ali-express.com, to camouflage clothing, vehicles, wearable technology and fragments of barely covered female bodies. The images of concealment bear the markings of different forms of control and power. Clérambault’s fetishist gaze is here equated with a more general voyeurism of and in society. Here in this damp basement, one becomes complicit in the gaze on the other.

Rosella Biscotti

Wilfried Lentz

February 8 – March 12

In the same building as A Tale of A Tub, Wilfried Lentz gallery presents two concurrent shows. On the top floor, Rosella Biscotti’s 'Crude Oil' (2016) comprises a series of rusty metal bowls containing layers of glass residue. The lower sediment consists of water-like transparent rough glass, while what floats above it is heavy and dark. All of the elements on display are involved in the process of blowing glass, but are usually discarded or obscured from view. Here, Biscotti draws a parallel between the detritus of the oil industry – interestingly, liquid glass takes on the same viscosity as oil at a certain point in the making process, something made apparent in these sculptures. This new work evokes those news images of spreading oil spills and the birds whose wings are covered in the heavy substance. ‘Crude Oil’ is both straightforward and disquieting in its tactility.

Main image: Bedroom, Sonneveld House, Rotterdam. Courtesy: © Johannes Schwartz, 2016