Critic's Guide: Tokyo

A guide to the best current shows in the capital of Japan

A guide to the best current shows in the capital of Japan

Seiichi Motohashi, 'Sense of Place'

Izu Photo Museum

7 February – 5 July

Located in the foothills of Mount Fuji, the Izu Photo Museum consistently stages some of the best exhibitions in Japan, and this retrospective of Seiichi Motohashi is no exception. It starts with the collection ‘Coal Mines’ (1964-ongoing), before moving through several essayistic series like ‘Ueno Station’ (1980-ongoing) and ‘Slaughterhouse’ (1986-ongoing) towards the haunting colour photographs of ‘Chernobyl’ (1991-ongoing).

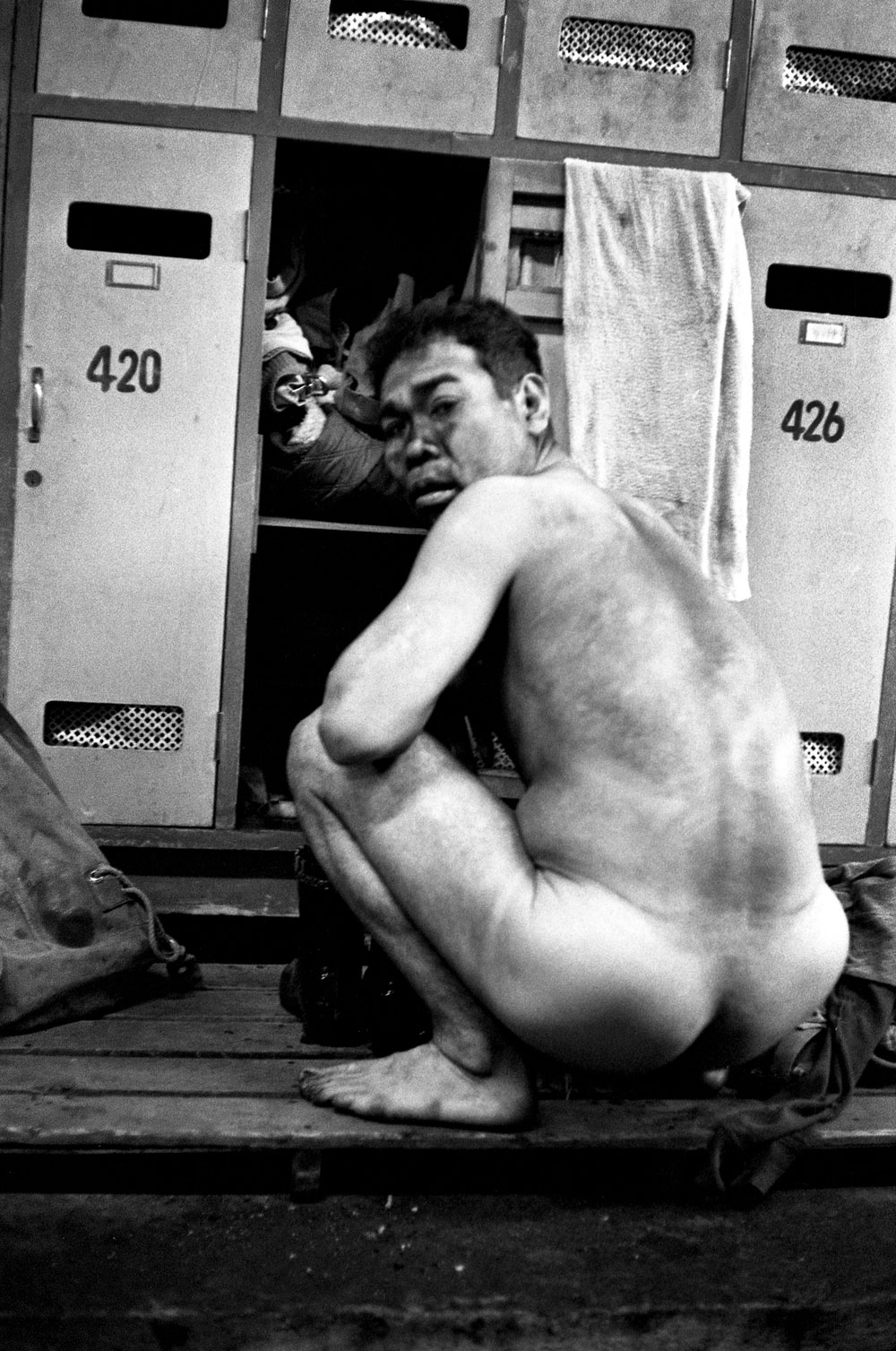

Motohashi captures a fraught sense of physicality that adds aesthetic punch to his on-the-spot documentation, as with a work from 'The Coal Mine' series taken in Hokkaido in 1968, a black and white portrait of a naked miner squatting before his locker in the company changing room. The black smudges covering the man's fleshy back and haunches read as both patches of coal dust and as grainy shadow – a kind of erased portrait. Mostly shot in Belarus, the ‘Chernobyl’ series takes on an added layer of significance in post-Fukushima Japan. Following the lives of those who defy authority to live in the contaminated zone, the pictures are almost insistently quotidian: people attend weddings and funerals, have picnics or enjoy quiet moments at home. Instead of opting for easy elegy, Motohashi shows subjects that do not ask for pity, and it lends his images an unsettling vagueness that hints at the mortality pervading all our lives.

Sion Sono, 'The Whispering Star'

The Watari Museum of Contemporary Art

3 April – 10 July

This glimpse into the world of prolific cult filmmaker Sion Sono coincides with the domestic release of his film of the same name, which follows a lifelike android as she travels from planet to planet, delivering packages for the 'Space Parcel Service'. Although the film’s 555-page storyboard dates back to the 1990s, the finished version is rooted in the contemporary context of post-disaster Japan, and was shot amongst the communities of evacuees from the Fukushima area who are still living in temporary housing. Spread across three levels of the Mario Botta-designed Watari-um building, the accompanying exhibition begins with an immersive installation. The walls are covered in wood and paper partitions, reminiscent of traditional shoji panels, through which can be seen animated silhouettes of people engaging in everyday family activities: eating at table, playing catch, practicing ballet. The nostalgia is laid on thick, but an incessant and indecipherable whispering that emanates from the ceiling suggests that everything is not as it seems. On the second level, Sono imagines a scenario in which the sculpture commemorating Hachiko the faithful dog, a landmark of Shibuya Station, has left its plinth and wandered to Fukushima. This is depicted through a series of replicas of the sculpture and plinth, as well as large photo prints of Hachiko in the exclusion zone. In one, he sits on an abandoned road before a billboard that proclaims, ‘Atomic Power: Energy for a Bright Future.’

Yuumi Domoto, 'Tami'

Gallery Koyanagi

27 May – 30 June

At the entrance to her exhibition of new paintings at Gallery Koyanagi, Yuumi Domoto has pasted a sheet of paper printed with the definition of the word tami, the title of the show. Translated, it reads: ‘The powerless masses; the segment of the population who are ruled; more broadly, people.’ Beneath is an explication of the Chinese character min, commonly used to represent tami in writing: a pictogram of an eye being pricked by a needle, min started out as a representation of a slave. (Not incidentally, min is one of the components in the word minshu shugi, or ‘democracy’.) These connotations of violence, control and oppression certainly tap into the zeitgeist at a time when the ruling Liberal Democratic Party is being widely critiqued for pursuing authoritarian measures in parliament and infringing the integrity of the constitution. What is odd, however, is that initially these welcoming definitions do not seem to bear any relation to the works inside, as if to illustrate the inherent arbitrariness of both language and images.

Domoto’s large canvases and smaller studies on paper test the boundaries between painterly abstraction, figuration and calligraphy, with thick dollops of white paint set against flattened, abstract backgrounds that recall pigment-based ‘Japanese-style’ modern paintings. With their rippled gradations from cobalt to pale blue, these backgrounds can evoke swirls of water, wind, or the soft focus of a camera. In turn, the overlaid muscular white forms can be flecks of foam, playful patterning, or the beginnings of cursive script. But if, as Domoto says, these flecks do represent people, then the interplay between the fussy backgrounds and the decisive gestures suggests the volatility of her subject matter, one that can cohere and then dissipate in an instant.

'Hisachika Takahashi by Yuki Okumura'

Le Forum at Maison Hermès

4 June – 4 September

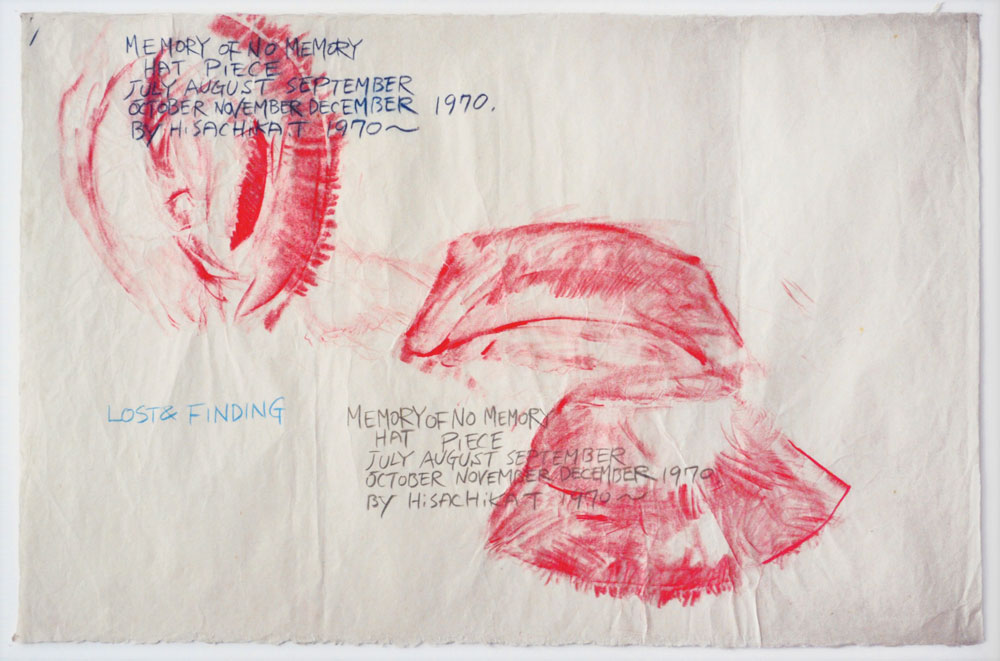

Part of the generation of post-Relational Aesthetics artists that are coming into their own in Japan, Yuki Okumura has spent the past several years channeling the life and work of the Zelig-like figure Hisachika Takahashi. In 1962, Takahashi left his homeland for Italy, where he worked briefly with Lucio Fontana before moving to the United States. There he spent four decades employed as Robert Rauschenberg’s studio assistant while moonlighting as a chef at Gordon Matta-Clark’s FOOD restaurant and pursuing his own artistic practice. Curated by Le Forum’s Reiko Setsuda, this joint exhibition between Okumura and Takahashi comprises a dizzying concatenation of frames and a maze-like structural intervention into Renzo Piano’s glass-bricked architecture. The centerpiece is the project ‘From Memory Draw a Map of the United States’ (1971-72), for which Takahashi invited 22 peers (including Rauschenberg, Matta-Clark, Cy Twombly and Joseph Kosuth) to perform the titular action, while a video in the entrance shows an interview in which Okumura responds to questions from the Swiss curator Daniel Baumann as if he were Takahashi. As cash-strapped museums increasingly turn to populist fare to generate income, and commercial galleries struggle to navigate a conservative domestic art market, this accomplished presentation is a reminder of the potential for institutions like Maison Hermès to function as incubators for artistic experimentation in Japan.

'The Voice Between: The Art and Poetry of Gozo Yoshimasu'

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

7 June – 7 August

While many visitors to MoMAT this summer will most likely make a beeline for ‘Modern Landscape’, a display of works from the gallery’s collection guest curated by Yoshitomo Nara, this impressive exhibition of avant-garde poet Gozo Yoshimasu should not be overlooked. Since his debut in the 1960s, Yoshimasu has developed a uniquely performative, multimedia approach to poetry. Here, his work is introduced through a generous selection of notebooks and manuscripts; photographic collages and montages with haiku-like titles (as in: The day I brought lotuses from (the old pond in) my house to Lyon, undated); hand-worked copper ‘scrolls’; over a thousand cassette tapes of voice recordings; and a number of experimental videos referred to as ‘gozoCiné’, which capture the artist, alone, conducting readings in the countryside to the accompaniment of bird calls and tape decks playing back different tracks. As befits an artist who is in constant dialogue with his cultural forebears and peers, works by other artists are included to further open the material: pencil drawings by John Cage, for example, or a new film installation made by dramaturge and artist Norimizu Ameya. Although those who don't read Japanese will inevitably struggle with the language barrier (Yoshimasu's tiny hand-writing, densely packed into the gridded drafting paper, is daunting even for natives), the theatrical exhibition design, with areas loosely sectioned off by curtains of porous black fabric that allow light and sounds to filter through, helps to communicate the sheer energy informing the artist’s vision.

'Sayonara Kaidan'

Misako & Rosen

12 June – 10 July

There was a time when Misako & Rosen was one of the most welcoming art venues in Tokyo. This was not down to the quality of their exhibitions and events alone, but also the result of the impromptu gatherings that would often occur there, something facilitated by the space itself. A wall-to-wall row of concrete steps descended from the entryway right into the heart of the sunken gallery area, creating an ad-hoc forum where people could sit and chat. In true Tokyo fashion, the steps are now gone for good, and Misako & Rosen has been temporarily displaced while the landlord rebuilds the property.

To pay homage, the gallery has asked four artists – Takashi Yasumura, Mie Morimoto, Motoyuki Daifu and Ayako Mogi – to photograph the demolition of the steps, with each photo hung within the one that follows, beginning from Yasumura’s tightly-framed detail of the pristine, rectilinear steps disappearing into a section of white wall, and ending with Mogi’s montage of views of the rubble. Although it is probably most meaningful for those who have been to the gallery, the exhibition is also a poignant reflection on the meaning of home in a city where the average lifespan of a building is said to be little more than two decades.

Miyako Ishiuchi, 'Frida Is'

Shiseido Gallery

28 June – 21 August

Although her practice spans several decades, photographer Miyako Ishiuchi is probably best known to international audiences for her ruminative ‘mother’s’ series (2000-05), which documents objects that belonged to her mother, from lipstick to negligees, and was shown in the Japan Pavilion at the 2005 Venice Biennale. For the series ‘Frida by Ishiuchi’ and ‘Frida: Love and Pain’, which were shot in 2012 at the Frida Kahlo Museum in Mexico City, Ishiuchi takes a similar approach, but exchanges obvious pathos for emotional complexity. With a handheld 35mm camera, colour film, natural light and neutral backdrops, she photographed objects that, following the instructions of Kahlo’s husband Diego Rivera, had spent over a half-century locked in storage. There is an understated exuberance to the once-vivid colours and worn textures of Kahlo’s buckled corsets, ankle-length Tehuana dresses, and fringed boots – all designed in response to the physical ailments that dogged her throughout her life. But there is a painful inscrutability as well, implicit in the passage of time and the displacement of corporeality inherent to photography itself. Reinforcing this dynamic, the walls of Shiseido Gallery have been painted blue, crimson, mustard and violet, echoing the environment of Kahlo’s home – known to locals as the Casa Azul, or the Blue House – and creating an interplay of colour among the various framed prints.