Dan Flavin

When I first saw Dan Flavin’s famous fluorescent tubes of light it was in a dark bunker at the Donald Judd Foundation in Marfa. Outside the temporary-looking trailers parked in the dirt and scattered brush of Southwestern Texas, the air was hot and dry, the sunlight blinding. But inside it was cool, quiet and pitch black, each trailer lit on the opposite end by only a few stripes of light. When you enter the exhibition ‘Dan Flavin: Drawing’ at The Morgan Library & Museum, the lights are most definitely on, and you’re greeted by the glow of a few of Flavin’s signature fluorescent tubes leaning against the corner by the gallery door as an assurance that the 100-plus ink and paper pieces on display before you are, indeed, by the very same artist.

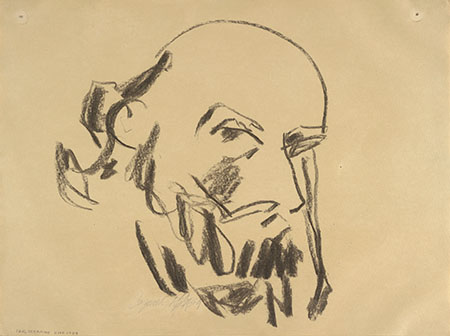

Even though it’s the light installations that we immediately associate with his name, Flavin didn’t begin to work with fluorescence until 1963, when he was 30 years old. Before that, he struggled to find the right medium, an effort that yielded a series of rich watercolours suggestive of the energy of Willem de Kooning, the wild gestures of Vincent van Gogh and the occasional found object in a nod to Robert Rauschenberg’s combines. If it sounds like Flavin was a bit of an art fan-boy, he was: he made portraits of Paul Cézanne and Constantin Brancusi, wrote adoring letters to Jasper Johns and dedicated works to Alexander Calder, later amassing a personal collection of Minimalist drawings, several of which are also on view here.

In the early ’60s, Flavin’s drawings evolved into plans and sketches for installations. He made eight ‘Icons’ from 1961–63, clumsy-looking wooden boxes to which lamps and light bulbs were attached like small-scale, DIY cinemae marquees. He called them ‘dumb – anonymous and inglorious […] They are constructed concentrations celebrating barren rooms. They bring a limited light.’ Still, Flavin was on the right track, remarking, ‘I will keep clarifying my art until it is not my own but everyone’s. At some point I will not even be sure of my direction any longer.’ This may sound as if he had lost his way, but in fact he was invoking a still-emergent Minimalist aesthetic. This was still a few years before ‘Primary Structures’, the seminal 1966 exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York that helped to establish the Minimalist movement.

After he abandoned his ‘Icons’, Flavin moved quickly. He realized the subject didn’t have to be a dead material surrounded by light-bulbs, but that the light itself could be the primary object. ‘One might not think of light as a matter of fact,’ he said later, ‘but I do. It’s as plain and open and direct an art as you will ever find.’ Starting in 1963, Flavin produced large batches of drawings that show his newfound enthusiasm with light, specifically with fluorescence. He even tried to create the effect of bright light in a dark room by drawing on black paper with coloured pencils. This is one of most exciting moments in the exhibition, as I suppose it was in Flavin’s own life. From here on out, his drawings were either quick sketches of idea for installations, finished drawings of installations (the coloured pencil and paper) or finished drawings on graph paper made to document his exhibitions. However, when viewed side by side with the real, bright-hot lights themselves, these case studies pale in comparison.

Still, Flavin admitted that drawing was his first love, and he continued to sketch throughout his career until just a few years before his death in 1996. The exhibition closes with some of his final pieces; pastels of sailboats, which sounds perfectly horrid until you realize that these are the most minimal sailboats you’ve ever seen. Some are frenetic, like the drawings he made in his 20s, with quick, itchy, Cy Twombly-esque pencil marks that show a persistent energy and spirit as bright as his glowing tubes of light.