Dorota Jurczak

If you are what you eat, how much of you is coming out the other end? The characters that inhabit Dorota Jurczak’s macabre world put a lot of work into where it goes. Curling it onto someone’s head from a height, lining the gallery floor with it – one anonymous pair of buttocks has even allowed theirs to become a home, from which five little men peek out. Jurczak’s exhibition ‘Smierdzace Balasem’ (Smelly Turd) was professedly scatological, but follow the faecal trails back up to the bodies that expelled them and you found eyes and anuses confronting your gaze. They stared back intently from windowsills and precipices, in a curious mix of defenestration and defecation.

Previous exhibitions of Jurczak’s work have focused more on the surreal narrative of her darkly whimsical etchings, a fragmented Gothic fantasy of intricately tangled webs and deformed animals. In a form of dementia reminiscent of the illustrations of Ralph Steadman (and his cited influences George Grosz and Otto Dix) these are glimpses into a grotesque carnival whose dreamlike qualities give the impression of providing access to a psychological unconscious. The gleeful use of shit as the thematic adhesive of her recent show amplifies Jurczak’s persistent knock on the door of Sigmund Freud, for her heavily symbolic iconography all too readily lends itself to psychoanalytic interpretation. She manages, however, to take playfully in her stride her own implications of the artist as anally expulsive, incorporating the art-as-shit and vice-versa gestures of, say, Piero Manzoni’s Merda d’artista (1961) and Wim Delvoye’s Cloaca (2000) into a more dramatized study of the physical environment her characters inhabit.

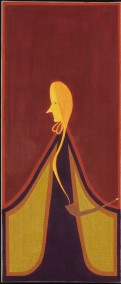

Jurczak’s etchings were present here, and this body of work retained a familiar disjointed, bristling absurdity, reminiscent of a lost scene from Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice (1988). But there is an added material awareness in which the etchings act as background settings alongside paintings and sculptures that flesh out and push at the imaginative limitations of her work. In the etching Fasada (Façade, 2006), a tower front with three windows is entangled in serpentine tentacles. From the top window a menacing dark head glares out. The same character gives the viewer a dead stare in Kokarda z weza (Ribbon of Snakes, 2007), as he crouches in the corner of a single windowpane suspended by the same searching tentacles. His bony hand stretches out from the frozen scene, reaching through a break in the glass as a wisp of smoke escapes from his ring finger to form a woman’s face. This is the ghostly sister of the figure in the painting Dym w Oknie (Smoke in Window, 2007), whose head rises from the smoke of a pipe. Depicted in warm hues, the woman’s body is also the drapery that manifests itself as the window of the title.

While some of the inhabitants of this realm look out from their windows, and others are themselves windows, it was Dwujek sraczki (Duncle Diarrhoea, 2007) who went one step further. Unlike Jurczak’s other defecators, who show us only their hairy arses hanging off windowsills, Duncle’s entire diminutive physique is painted on a wooden panel, his head and rear connected by an anatomy of engraved flowers and flourishes. A thick brown mass began on the floor just below the painting, skirting the edge of the gallery to trail off sneakily around a corner. His (admittedly fairly tidy) mess seemed to be not just an isolated accidental bowel movement, however, but part of a movement towards bodily realization. The eponymous Smierdzace balasem (2007) rose up in the middle of the room, a small brown sculpture in the shape of a turd with the consistency of a soft-serve ice cream. The ‘smell’ wafted up from the sculpture to morph into the shape of a caricatured head, whose genie-like presence seemed part of an invasion into the third dimension: a capped head pops out the top of the striped Laska (Walking Stick, 2007), while in the corner a sinister face emerges in the place of a bulb in Lampa (Lamp, 2007).

At its best, ‘Smierdzace Balasem’ saw Jurczak exploring her imagination in more explicitly material terms; a movement away from psychological illustration that suggests that we can look forward to whatever comes out next.