Emily Karaka Champions Indigenous Justice Through Painting

In her first major survey at Sharjah Art Foundation, the senior Māori artist’s vibrant, political landscapes highlight global indigenous struggles

In her first major survey at Sharjah Art Foundation, the senior Māori artist’s vibrant, political landscapes highlight global indigenous struggles

Central to Emily Karaka’s expressive practice is the Treaty of Waitangi, the founding document of Aotearoa New Zealand. Signed in 1840, the treaty was an agreement between the British Crown and more than 500 Māori chiefs. Its quasi-legal status, not to mention the differences between the English and Māori versions, would lead to the New Zealand Wars (1845–72), and a subsequent loss of ancestral land through confiscation and settler occupation. Karaka’s large, semi-abstract, text-heavy paintings unspool the ongoing aftermath of this document to advocate for Māori stewardship of their own lands and to serve as a ledger of the slow and painful process of reparations.

Remarkably, despite Karaka’s renown as a senior Māori artist with a career spanning five decades, ‘Ka Awatea, A New Dawn’ is the first major survey of her largely self-taught practice. Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi and Megan Tamati-Quennell, the works on view are drawn from both public and private collections and include new pieces commissioned for this show. They are arranged chronologically, moving from her dark, vegetal early canvases through to the riotously bright ‘political landscapes’ – to quote the wall text – of her later years, which plot both terrain and its hard-won reclamation. Many paintings are unstretched, extending their cartographic feel. Particularly seductive are Rangitoto – Karanga and Rangitoto Eruption (both 1988), a pair of works comparing the upheaval of the land-rights movement to a volcanic eruption, and featuring wooden lintels beautifully carved to depict kaitiaki – spiritual guardians of the environment.

For lifelong activist Karaka, it is the political that is personal. Although the Claude Monet-inspired The Painted Dream Garden (1991) celebrates the birth of her first grandchild, her works mostly address milestones of an expanded idea of family: from her iwi (tribe) to the broader Māori community to indigenous people everywhere. DNA (2022) makes explicit this emphasis on whakapapa (genealogy) in its depictions of four historical female Māori leaders who variously opposed conscription or incited occupations and marches. At its centre is Karaka herself, wearing the cloak of her warrior chief ancestor Kiwi Tãmaki, and brandishing her own weapon of choice: a paintbrush.

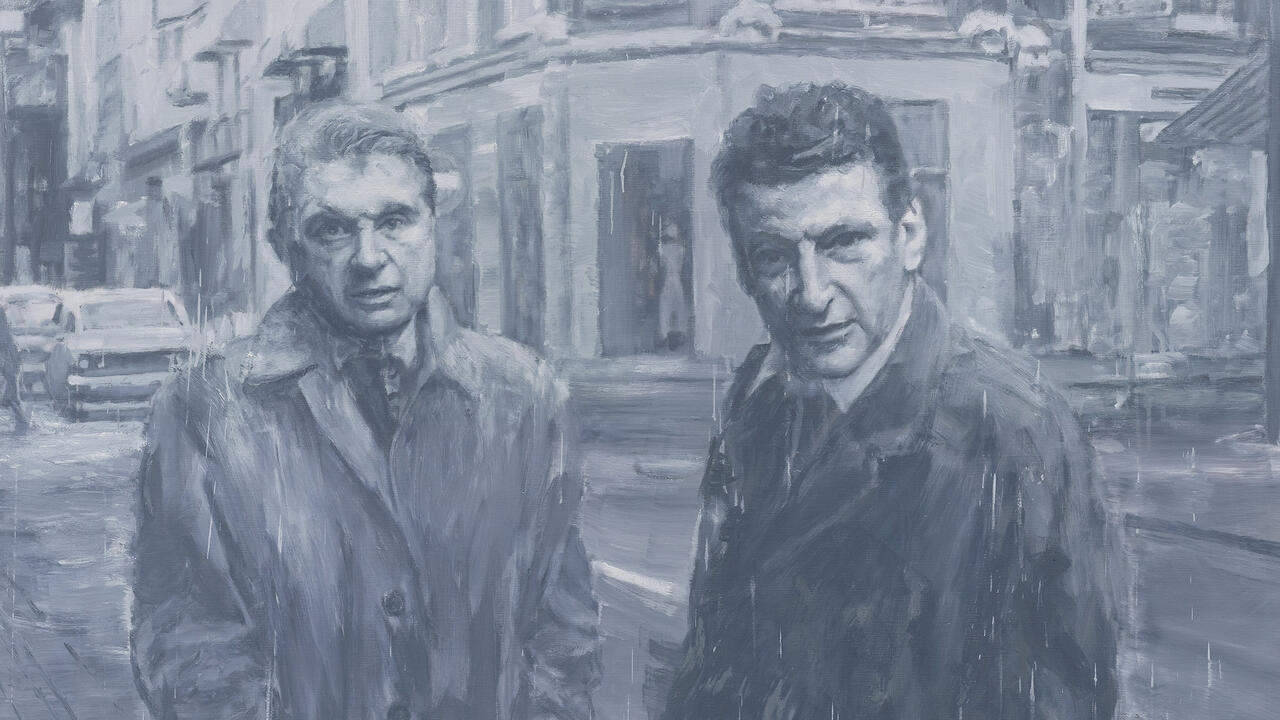

Throughout, Karaka draws links between iwi rights and global indigenous struggles. The moody 1984 triptych The Treaties, for example, references the Commonwealth’s 1977 Gleneagles Agreement that worked to combat South African apartheid. And in her new work Parallel Process: Palestinian Horizon (2024), the slings and arrows of settler colonialism are more overtly referenced with Israeli and Palestinian flags and the slogan ‘the promised land’. Collective global anxieties underscore our interconnectedness in works such as Nuclear Mother (1984), which addresses fears of nuclear armament and its environmental impact, while later pieces, including NFIP (Nuclear Free Independent Pacific) Flowers No Nukes (2004), celebrate New Zealand’s establishment as a stringently nuclear-free zone. More recently, I can’t breathe (2021) – one of a trio of paintings that traces connections between the COVID-19 lockdowns and the dieback epidemic of the sacred native kauri tree – poignantly also features Eric Garner’s last words.

‘Ka Awatea, A New Dawn’ opens at a time when Palestine continues to be decimated and land rights can increasingly feel like a pipe dream. The works faithfully chart setbacks, like the establishment of the Auckland supercity in the series ‘Māori Pride/Rodney Hide’ (2010–11), along with victories such as the defeat of an attempt to introduce a financial cap on all Treaty of Waitangi settlements in perpetuity in Inside the Envelope (2012). Yet, even when reparations can feel like a game of snakes and ladders, as depicted in Tiriti Settlement Process (2015), the show provides an optimistic example of indigenous justice as it could be.

Emily Karaka’s ‘Ka Awatea, A New Dawn’ is on view at Sharjah Art Foundation until 1 December

Main image: Emily Karaka,The Painted Dream Garden, 1991, oil, acrylic & pastel on two sheets of paper, abutted. Collection of Museum of New Zealand Te PapaTongarewa. Courtesy: Sharjah Art Foundation; photograph: Motaz Mawid