Everything is Connected: Art and Conspiracy at the Met Breuer

In New York, a so-called ‘exhibition’ at a ‘museum’ featuring 30 ‘artists’? Dan Fox uncovers the truth behind this dangerously timely show

In New York, a so-called ‘exhibition’ at a ‘museum’ featuring 30 ‘artists’? Dan Fox uncovers the truth behind this dangerously timely show

The Met Breuer – host to the exhibition ‘Everything is Connected: Art and Conspiracy’ – is located at 945 Madison Avenue, New York. By applying a basic alpha-numeric cipher we find that the numbers 9, 4 and 5 tally to the letters I, D and E in the alphabet. Swap the ‘I’ with the ‘D’ and we have the word ‘DIE’. It can be no coincidence that this Marcel Breuer-designed building was completed in 1966. Turn the ‘9’ upside-down and we get Satan’s numerical ID, ’666’: 1 + 666 means Number One, Six Six Six, aka First or Premiere Demon, also the year of the Great Fire of London and Isaac Newton’s discovery of gravity. (Surprising that a more sophisticated encoding system was not used by the George Soros-funded operatives who buried a copy of the Necronomicon in the foundations of the museum during its construction.) Now consider that trapezoid-shaped single window on the museum’s upper facade. Turn it 90 degrees counter-clockwise and you’ll notice it forms the middle section of a triangle, which corresponds to the mid-section of the Masonic hierarchy pyramid; a list of secret societies including the Illuminati, the Ordo Templi Orientis, and The Order of the Trapezoid. Avant-garde filmmaker and occulist Kenneth Anger is a member of the Ordo Templi Orientis. His work was shown at the Breuer in 1975 when the building was masquerading as the so-called ‘Whitney Museum of American Art.’

Educated observers will note that in order to enter the Breuer, visitors must cross a bridge over what is clearly a moat, easily fortified by filling it with toxic water, pre-poisoned for such purpose by Islamist cells operating in Flint, Michigan. Why does this museum have so few windows and such thick concrete walls? How many art works have you seen on view here, but never witnessed actually leaving the museum after the show has closed? Could it be that a collection of priceless artworks is being brought in under the guise of a temporary exhibition, then hoarded in a bomb-proof storage facility beneath the building in preparation for the New Civil War, when Manhattan will be closed off and turned into a heavily-defended enclave for the global elites, who will be able to enjoy masterpieces of global art in safety whilst everyone else perishes in lawless zones beyond the banks of the Hudson and East Rivers, overrun by illegal immigrant warlords indoctrinated into radical socialism by Hilary Clinton at the Comet Ping Pong pizza restaurant? I mean, you only have to take a map of the island and draw a line linking the locations of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New Museum, Museum of Modern Art, Metropolitan Museum, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Neue Galerie, Frick Collection and the Jewish Museum, to reveal a reversed ‘L’ shape. And what does the ‘L’ stand for? That’s right. Liberals. Leftists. Luciferians. Also, Led Zeppelin, whose recording of ‘Stairway to Heaven’ transmits the message ‘Here’s to my sweet Satan’ when played backwards.

The organizers behind ‘Everything is Connected’ are masters at hiding in plain sight. Douglas Eklund’s Swedish last name means ‘oak grove’. His job is in the arts. So, obviously, Eklund = Bohemian Grove i.e. an occult ceremony for the Bilderberg Group aka Illuminati held in California every year. The last name of his co-curator, Ian Alteveer, is an anagram of ‘revelate’ i.e. Book of Revelation therefore the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse thus you will D.I.E., or I.D.E., ie. 945 Madison Ave, to whit, the IDEs of March = 15 March, aka the Roman deadline for settling debts, i.e. the murder of Julius Caesar which is the archetype for all state assassinations. JFK, anyone? The Met alleges that Eklund and Alteveer were ‘assisted’ in putting this show together by Meredith Brown and Beth Saunders. Assistants, or powers behind the throne? You decide. I’ll take the fact that these curators have made no attempt to contact me since I started writing this piece as a coded warning that I should watch what I say and write a straight-up exhibition review instead. If the Met chooses to advertise in frieze following publication of this piece, it’s clearly a sign that they’re scared and think they can control me through money. This is the kind of shit that happens when the forces of Big Museum flex their muscles.

The story that Eklund and Alteveer want us to believe is that their exhibition is the first major show to examine the batteries of paranoia that fuel Western democracies, specifically the US. It plays to Richard Hofstader’s 1964 essay ‘The Paranoid Style in American Politics’, which argues that the US has always made room for ’heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy.’ The history of this country has been shaped by fears that outsiders will infiltrate it or insiders will bring it down from within. ‘Us’ versus ‘them,’ and you name them, someone’s blamed them: Indians, French, British, Irish, Mexicans, Iranians, Catholics, Jews, Muslims, Rosicrucians, Mormons, freemasons, hippies, bikers, black revolutionaries, gays, atheists, communists, Nazis, bankers, socialists, satanists, witches, aliens, advertising companies, rappers, rock’n’rollers and Dungeons & Dragons players. (In 1987, Tipper Gore claimed in her book Raising PG Kids in an X-Rated Society that D&D was ‘linked to nearly fifty teenage suicides and homicides.’) Understand the history of American paranoia and how it legitimates violence, and you will understand how Donald Trump’s lies gain traction, steroid-boosted by Sean Hannity, Alex Jones and other credulous, craven conservative loudmouths. But I’ve said too much already. ‘They’ still think that I think that Fox News is news targeted specifically at Dan Fox. Fools.

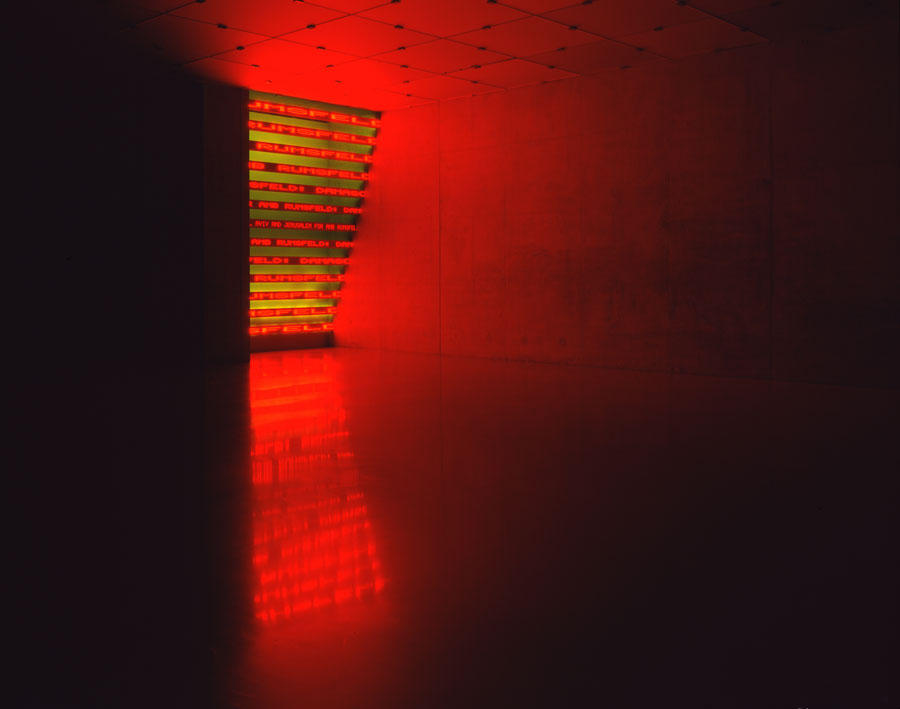

‘Everything is Connected’ – or is it? – broadly splits its 30 artists into two sections. (Divide and rule. Classic seditionary tactic.) The first looks at how artists have used research and information in the public realm to work as citizen journalists, revealing secret business interests and ideological alliances that the powers-that-be would prefer to remain hidden from view. Here are Mark Lombardi’s elegant and frightening ‘narrative structures’; spider diagrams which show links between figures in finance, government and the military-industrial complex. Jenny Holzer’s digital ticker-tapes use language taken from classified government documents, and Trevor Paglen’s photographs depict CIA ‘black site’ prisons – images all the more sinister for their banality. Hans Haacke’s Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971– (1971) is here too. Haacke shone his interrogation lamp on slumlord ownership in New York, which infamously led to the cancellation of his exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum that year, along with the dismissal of curator Edward Fry. The section also features illustrations made by Emory Douglas for the Black Panthers, and ACT UP’s iconic poster SILENCE = DEATH (1987). ACT UP brought to attention the Reagan administration’s refusal to acknowledge the AIDS crisis. Arguably both of these are less ‘about’ conspiracy than engaged in real struggle against it.

It’s tin-foil hat time in the second half. Rachel Harrison’s installation Snake in the Grass (1997) pulls photographs taken on the ‘grassy knoll’ in Dallas into a web of taut ropes, which look like the work of feverish Kennedy assassination theorists trying to figure out lone gunman ballistics. Jim Shaw connects JFK’s death to little green men in his UFO Photos: Zapruder Film (1978–82), which finds flying saucers in Abraham Zapruder’s footage of the Kennedy shooting. Mike Kelley satirizes the ‘Satanic panic’ child abuse rumours of the 1980s in his ‘Educational Complex’ (1995). On a long display table are architectural models of every educational institution the artist attended: underneath the table, as if locked in a hidden basement or the subconscious, lurks a small, grubby mattress. But these are almost affectionate play-acts of paranoia. Darker stories of real exploitation lurk in Sarah Anne Johnson’s disturbing sculpture House on Fire (2008–09), and the suite of hand-doctored photographs which accompany it. Johnson evokes the terrible psychological distress suffered by her grandmother who was duped into the CIA’s MK-ULTRA project in the 1960s – an experiment in using psychotropic drugs to control minds – under the pretext of being treated for post-natal depression.

The idea to stage ‘Everything is Connected’ came from a 1991 interview between John Miller (also included in the show) and Kelley. According to the Met, Kelley had seen an early version of the checklist for the show before his death in 2012, enthusiastically suggesting additional artists and ideas. Kelley’s art detailed the landscape of the American Weird like no other, and his spirit of imaginative, playful skepticism, his fondness for the far-out, permeates this show. It suggests that the most imaginative acts of art-making are those that are willing to make tangential leaps of faith and counter-intuitive connections.

In the video Winchester (2002) by Jeremy Blake, the artist attempts to get inside the fearful, paranoid mind of Sarah Winchester. Widow of the heir to the Winchester rifle fortune, she spent almost four decades from the end of the 1800s in never-ending construction on her California mansion, believing this would appease the spirits who had cursed her family. Historical photographs and ink drawings float and merge into one another. Visual connections appear then evanesce, leaving you to wonder if you had seen or merely imagined them. An uneasy idea, easily intuited from Winchester, is that the suspicious, superstitious or conspiratorial mind, ever vigilant for new dots to connect, is also a creative one. The Comte de Lautréamont’s line about ‘the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table’ is both a Surrealist maxim and a fair description of the conspiracist theorist’s imaginative short circuits.

Close followers of the art world might detect stranger, sadder resonances in ‘Everything is Connected.’ The deaths of Blake and his partner Theresa Duncan in 2007 were shadowed by rumours of harrassment by the Scientologists. Lombardi took his life in 2000, in circumstances that his biographer Patricia Goldstone has argued were suspicious; in the weeks following Kelley’s suicide, there was ghoulish speculation that the pressures of art market success had led him to take his. The reasons for all these deaths are too complex and tragic for anyone to know the real truth. But the art world still loves to write its own micro-conspiracy theories about money and careers: if you feel unrecognized by the industry, then it’s natural to try and rationalize your lack of agency by intuiting invisible forces ranged against you. ‘Gods always behave like the people who make them,’ said Zora Neale Hurston. The truth behind an overlooked or scuppered career is often more depressingly banal than fiction wishes, yet in the instances where gender and race are a factor in someone’s disempowerment, a belief in invisible forces of oppression is usually well-founded.

As if to literally illustrate the exhibition title, the end of the second, wilder, section of ‘Everything is Connected’ takes viewers back to the more sober start of the first. But make a repeat circuit around the show and you will drag behind you, like LSD-laced chemtrails, the idiosyncractic, folkloric, macabre, fringe fascinations of Kelley, Shaw, Miller, Johnson, Sue Williams and others. Now the sensibilities of the first and second halves of the exhibition don’t seem so different from each other. Questions emerge and the curators aren’t giving up any answers. Why do we believe what artists say, and always presume them to be on the side of progressive values? Why do ‘research-based practices’ that never get peer-reviewed, and citizen-journalist works about politics that never get passed by editors or fact-checkers, be given credence as journalism? Do artists receive the benefit of the doubt because, deep down, we still cling to a Romantic belief that the artist is the conduit for higher truths? Or is it because to risk the idea that an artist could be wrong in their assertions might jeopardize all the systems that support them, and accidentally plunge art into the Bermuda Triangle of ‘fake news’?

Then again, what if artists are right? Haacke was. ACT UP were. The Black Panthers too. Quite possibly, so was Lombardi. In her 2015 biography of the artist, Art, Conspiracy and the Shadow Worlds of Mark Lombardi, Goldstone reveals that months after the artist’s suicide in 2000, and following the 9/11 attacks, the FBI visited the Whitney Museum asking that it remove one of his drawings linking the Bank of Credit and Commerce International to Saudi-funded terrorist networks. Where do the responsibilities of creative people lay? Conspiracy theorists today derive their ideas and language from culture, especially movies and television. Neo-fascists describe their conversion to the right as being ‘red-pilled’, a reference to The Matrix movie trilogy in which Keanu Reeves’ character Neo is given a tablet that, when swallowed, shows him the true nature of reality. The quasi-military jargon that conspiracists employ in order to give legitimacy and the appearance of expertise to their speculations – talk of agents, deep state operatives, false flag operations, disinformation campaigns and so on – is more likely learned from episodes of The X-Files and Homeland than it is from real sources in the intelligence community. The register of language in which individuals such as Robert Bowers write to justify their vile ideology – he is currently charged with 29 federal crimes relating to the murder of eleven people and wounding of seven others at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh – reads as if it is straight out of an action film. ‘I can’t sit by and watch my people get slaughtered. Screw your optics. I’m going in,’ was his final posting to the social network Gab before the shooting. Histrionic, macho one-liners learned from the movies but delivered by nobody’s hero.

I could continue, but I’ve just noticed a dot of red light moving across my window. A sniper’s laser-guided telescopic sight? It’s gone now. Must have been the reflection from a passing car tail-light. Probably a Mossad surveillance vehicle. Or MoMA. In any case, I guess you’re wondering who’s paying me to write all this, so let me map the money trail for you. The cover story is that I get paid by frieze with money generated from advertising, subscription and newsstand sales. Truth is, the ads money is made to appear as if it comes from multiple sources – galleries, museums, consumer brands – but these are merely front organizations processing payments made by a centralized funding source controlled by – wait, there’s that red laser dot again, hovering over my chest …

Main image: Peter Saul, Government of California (detail), 1969, acrylic on canvas. Courtesy: Collection of KAWS