Everything We Do Is Music

How Indian classical music has influenced the visual arts

How Indian classical music has influenced the visual arts

Sitting cross-legged on a low stool in front of a drafting table in a sparsely furnished studio in Vadorada (formerly Baroda), India, Nasreen Mohamedi would draw late into the night listening to Hindustani classical music. Observing the asymmetrical grids and floating diagonals of the artist’s pristine compositions, it is hard not to wonder what relationships might be found between the artworks and the melodies and vibrations of the music.

The origins of Indian classical music are generally traced back to the Vedas, the oldest of the Hindu scriptures, which date from c.1500 BCE. The Vedas comprise four parts and, of these, it is the Samveda — a collection of melodies containing 1,603 verses — that is the foundation of Indian music. Chanted by priests, these hymns would eventually evolve into ragas: a selection of five, six or seven notes distributed along the scale, making room for a melodic framework of improvisation. It also includes a single main note to which the singer constantly returns.

Over time, two schools of Indian classical music have developed. In northern India, there is Hindustani classical music, where ragas tend to be classified according to a mood, season or even time of day. In the south, there is Carnatic music: ragas clustered by the technical traits of their scales. It is important to note that Indian classical music has developed through the oral tradition as opposed to notation; what is significant is the exchange between instructor and student.

So, how does something as distinct as Indian classical music find itself connected with the visual arts? Returning to Mohamedi: on 17 February 1960, she wrote in her diary, ‘music–abstract quality and yet real to such a degree that is almost life’. The infinite variations in her drawings evoke the improvisational tenets of the music she so enjoyed. Yet, as Mohamedi’s close friend and art critic, Geeta Kapur, proposed: ‘Nasreen wanted to embody and be engulfed by such structured resonance — the phenomenology of deep, full sound offered her relational sentience; it also gifted her solitude.’1

Indian music has provided artists with an inspiration that can assume forms ranging from the abstract to the conceptual and the subliminal.

In his 1990 ‘Autobiographical Statement’, John Cage declared: ‘The purpose of music is to sober and quiet the mind, thus making it susceptible to divine influences.’ Cage arrived at his conclusion via the Indian musician Geeta Sarabhai, who had introduced him to Indian classical music and philosophy. Cage soon began work on his Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano (1946–48) under the influence of the Indian theory of the nine rasas, or emotions. As with Mohamedi, Cage was less interested in finding a way formally to represent Indian classical music than in dwelling on the role it could play in ordering subjective experiences.

Although neither Mohamedi nor Cage — nor, for that matter, other Modernists such as Vidya Sagar and Zahoor ul Akhlaq — overtly reference Indian classical music in their work, there is a history of musical representation in the arts in India. The Indian scholar Dr. Narayana Menon has explained that, in archaeological finds, musical representation takes one of two forms: it is either a graphic depiction of musicians and dancers or it is an attempt go beyond physical qualities, opting instead to denote an associated mood or character of a particular raga. This is most palpably manifest in miniatures, especially those from north India. Known as ragamalas, these paintings have been identified as a specific genre emerging in the second half of the 15th century. However, their roots go further back to the Brihaddeshi text (c.7th century), which was the first time the raga had been directly written about.

Many artists who were active in the early-to-mid 20th century harnessed this unique heritage of musical representation. The great Bengali polymath, Rabindranath Tagore, for instance, was a prolific composer

of Rabindrasangit: a new type of music that fused classical ragas with fixed melodic compositions. The Rabindrasangit was borne from Tagore’s experience of both Western and Hindustani music. Y.G. Srimati, a painter from southern India, received early training as a classical vocalist and enjoyed a reputation as a highly accomplished performer. Parallel to her career as a vocalist, Srimati also painted prodigiously; her aesthetic was strongly influenced by another pioneer of Modernism in India, Nandalal Bose. The sculptor Meera Mukherjee, who studied under Toni Stadler in Germany in the 1950s, was also trained in Hindustani classical music and made numerous sculptures of musicians and dancers, combining the European lost-wax process of casting bronze with indigenous methods of improvised casting.

The French historian and intellectual Alain Daniélou, along with his partner, the photographer Raymond Burnier, visited India in 1932, and soon moved to Benares where he studied Indian classical music, eventually writing two books on the region’s music. Along with the educator and singer Omkarnath Thakur, Daniélou founded the first musicology department of the Benaras Hindu University. Daniélou and Burnier’s home, Rewa Kothi, was transformed into a salon de musique and recording studio that hosted musicians including Ali Akbar, Raghunath Prasanna and Ravi Shankar. When the Italian artist Francesco Clemente was living in Benaras, he did a series of watercolours titled ‘Evening Ragas’ (1992). As he explained: ‘I used evening raga instead of day because, to my mind, the overall theme was metamorphosis — activities of the mind connected with dreams and sleep. Nonconscious decisions. The images work on variations of this theme and each group is kept together by a mood, flavour, that you keep in mind.’2

Indian classical music also served as an inspiration for a host of mid-century avant-garde American composers and underground art-makers. These include La Monte Young and his partner Marian Zazeela, who fostered their connection with Indian music via the musician Pandit Pran Nath, and who, according to the writer Alexander Keefe, ‘forged an alternative, cosmopolitan model for the future of South Asian traditional music, one focused on advanced sound technologies, spiritualized sensibilities’.3 The most extreme manifestation of Young and Zazeela’s experiments resulted in their Dia Foundation-funded sound and light environment, Dream House, ideas for which originated as early as 1962, but which first took shape in Soho, New York, in 1975. Analogously, in 1971, the French artist Tania Mouraud created her ‘Initiation Rooms’, a series of white sensory-lit environments in which Pran Nath, Terry Riley, Young and Zazeela were invited to perform. Mourand believed that experiencing music performed in such an environment would create heightened self-awareness.

Similar sensory explorations with Indian music preoccupied the Argentinian experimental filmmaker Claudio Caldini; in 1976, he made the film Vadi-Samvadi: the title is a reference to the notes of a raga. Indian classical music forms the soundtrack to a scene in which Caldini sits at a desk operating a miniature steam engine; this is followed by a four-minute sequence drenched in stroboscopic effects. Even more metaphysical is Bruce Conner’s final film Easter Morning (1966‒2008), which comprises a hypnotic blur of colour and multiple exposures derived from an earlier 8mm cinema short he originally filmed in the 1960s as Easter Morning Raga. The film was never released and Conner reworked the footage and set it to Terry Riley’s In C (1964).

While the Dream House and ‘Initiation Rooms’ are dedicated environments for contemplation and introspection, the German artist Michael Müller has used performances of Indian classical music to inspire his art-making. In 2010, he created two large canvases: Musikstück (Megh) at Daybreak and Musikstück (Madhuvanti), Played Wrongly at Noon (both 2010), the titles indicating what the artist was listening to when he created the works. Another approach to notation-based art-making can be seen in Lala Rukh’s modest series of drawings, ‘Hieroglyphics’ (1995–ongoing). These works present a personalized abstracted language that echoes musical notation; perhaps it should come as no surprise that Rukh’s father ran the All Pakistan Music Conference.

A more direct presentation of how the body experiences Indian classical music is illustrated by Hetain Patel in his video Kanku Raga (2007), in which the artist assigns each stroke of the tabla drum to a different movement of marking or erasing Kanku pigment from the body. The result is a dissected rhythm presented both visually and audibly. Performing each part, Patel highlights the idea of instilling cultural rhythm physically within the body through repetition. This question of personalized and performed notation is a thought-provoking one to raise in light of Indian classical music’s relationship to an oral tradition. What are the implications of creating such notational systems? Do they fix the music or do they, rather, represent a subjective experience of the melody at a particular moment, tracing that instant of exchange between artist and composition in which the artist is simultaneously listener and performer?

Indian classical music has also allowed artists to express an abiding sense of melancholy. Take, for instance, the photographer Derry Moore, who titled his book about the last vestiges of a pre-modernized India Evening Ragas (1997) — despite the fact that he included no photographs of musicians or musical performances. Similarly, Sudarshan Shetty in his video Waiting for Others to Arrive (2013) lays the plaintive wail of the sarangai on top of images of a shattering teacup and a colonial building waiting to be demolished.

Of course, numerous photographers have attempted to document the musicians of the Indian subcontinent. Raghu Rai’s black and white photographs of Indian musicians, which were shot for the magazine India Today in the mid-1980s, are a valuable documentary ecord. Similarly, the artist Dayanita Singh made the tabla player Zakir Hussain the subject of her first photo book, which is titled after the musician, in 1986. However, for Singh it was about more than simply photographing Hussain; what she really learnt from him is the ‘rigour and restraint’ of Indian classical music. ‘Unlike Western classical music, where all the notes are fixed and you interpret rather than elaborate, here you have these fixed notes on which you have to elaborate. It’s a question of how you combine these notes, and that’s your genius.’4

Clearly, Indian classical music has provided countless artists with an inspiration that can assume forms ranging from the abstract to the conceptual to the subliminal. As the great Ceylonese scholar, art historian and curator Ananda Coomaraswamy wrote in 1917: ‘Our attitude towards an unknown art should be far from the sentimental or romantic, for it can bring to us nothing that we have not already with us in our own hearts: the peace of the Abyss which underlies all art is one and the same whether we find it in Europe or Asia.’5 Thankfully, many artists have taken heed of his counsel.

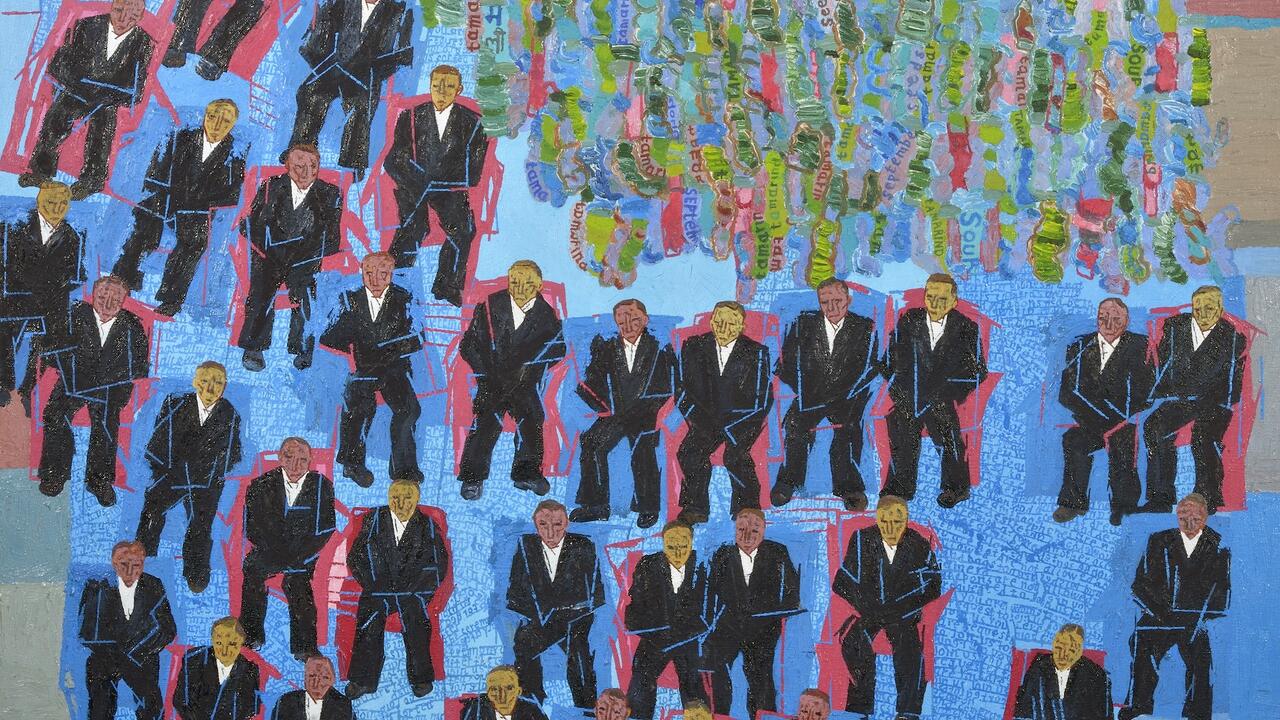

Main image: Dayanita Singh, Zakir Hussain Maquette (detail), 2019. Courtesy: the artist, Steidl, Göttingen and Frith Street Gallery

An exhibition of paintings by Y.G. Srimati will open at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA, in December 2016.

1. Geeta Kapur, ‘Again a Difficult Task Begins’ in Nasreen Mohamedi: Waiting is a Part of Intense Living, Museum Nacional Centro De Art Reina Sofia, Madrid, 2015, p. 163

2. Francesco Clemente quoted in The Allen Ginsberg Project, http://tinyurl.com/gonm6tb

3. Alexander Keefe, ‘Lord of the Drone: Pandit Pran Nath and the American Underground’, in Bidoun, Issue 20, 2013

4. Quoted in ‘In Conversation: Stephanie Rosenthal and Dayanita Singh’ in Dayanita Singh: Go Away Closer, Hayward Publishing, 2013, p.57

5. Ananda Coomaraswamy, ‘Indian Music’ in The Musical Quarterly, Volume 3, Oxford University Press, 1917, p.172