Fabian Marti

Posters, pots and fingerprints

Posters, pots and fingerprints

Modernity is marked by a great divide between man and machine, handcraft and mechanical reproduction. While some Modernists embraced crafts – think of Bauhaus – others like the Futurists favoured machines and mass production. The Zurich-based artist Fabian Marti uses hybrid methods like ceramics and photograms that straddle this divide. His works – marked by both the unique fingerprint and the repetitive grid – question the origins of creativity and authorship.

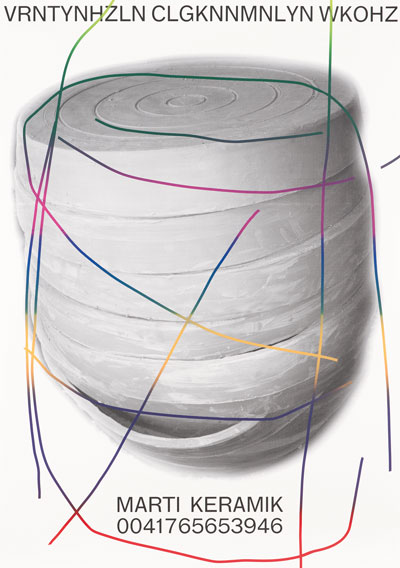

Consider Marti’s poster VRNTYNHZLN CLGKNNMNLYN WKOHZ Marti Keramik 0041765653946 (2011), which uses both mysterious codes and unambiguous contact details. The title could easily be taken for an advert for a building contractor: stating the product code, the contractor’s name and trade along with a Swiss phone number. The poster features not only the title information but also a white ceramic pot. Although unglazed, its surface is fully formed: a tubby, closed vessel whose piled horizontal rings are sealed with a flat top that suggests a potter’s spinning wheel – a motif that occurs repeatedly in the artist’s ceramics. There is also an irregular tangle of lines, drawn in various colours: from neon yellow to violet to green.

Since 2011, similar lines have appeared on the surface of many of the artist’s other objects, photograms and architectural interventions. In the photogram Youth! Youth! (2011), layers of freehand overlap technical drawings. Hand prints appear across a grid of holes cut into photographic paper, which is also marked by scrawled lines. Some areas of the black and white image lie under a semi-transparent cloud of red, green and blue, clearly added after the image was developed. The production of a traditional photogram ends in the darkroom, but Marti keeps on adding newly hand-crafted layers to the surface of the photographic paper.

At first glance, the traces of his gestures have an almost abstract expressionist feel. Yet painterly categories can hardly be ascribed to this work precisely because it combines manual and mechanical means of reproduction. Hand prints appear throughout his oeuvre – on photograms, on ceramics and as life-size stickers (End Egoic Mind, 2010) – yet always in the same manner, as if Marti were turning the hand print – the ultimate marker of individual and artistic identity – into a massproduced product. Here, the artist questions the Modernist notion of a signature style with an ironic, literal reading of the fingerprint as photographic print.

In his latest film, Because I Travel a Lot (2011), we hear the voice of a woman narrator describing a return to a prehistoric culture, before tools and stylistic conventions. The recited text, from the late ethnopharmacologist Terence McKenna, explains that our received culture is a mere operating system which can be rebooted by using psychoactive substances. For McKenna, such drugs hold the key for overcoming ‘Capitalism 5.0’ and a return to the ancient ‘animal soul’ of humanity. As we listen, we see a ceramic object being made which resembles the one used for the Marti Keramik … poster. In the hands of a skilled craftsman, a lump of clay becomes a round object, built up by laying bands of clay on top of one another and finished with a coloured glaze. We hear the hypnotic spinning of the potter’s wheel and a mix of muffled drumming and synthesizer sounds. The footage could well have been taken by a team of ethnographers, documenting a recently discovered exotic culture. After following every step of the production process, we see the finished ceramic once again but against a black background, as if it were already in a museum.

For his exhibitions, Marti often designs his own display units using MDF walls, plinths and items of furniture which are precisely made but tend to look somehow clunky. While he leaves signs of a direct physical contact with his materials, there’s a playful distance to the resulting art works – a distance that effectively conceals the identity of the artist as the producer of both the works and their displays. By moving between anonymity and identity, he turns the creative impulse into a primal question: not only who and what makes art but why it is made in the first place.

Translated by Nicholas Grindell