Felix Gmelin

Perhaps the work of art with the most to say about the charisma of revolutions is the one that finds the least to say by way of recommendation: Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day (1877). Near the Gare St-Lazare the grandchildren of the Parisians who stormed the Bastille stroll Baron Haussmann’s new city in the drizzle. Dank melancholy is their purchase on an alienated urban life filled with empty leisure among avenues too broad for barricades.

Felix Gmelin’s unblinking picking over of the bones of the revolutionary spirit recreates the hard political lessons Caillebotte framed more than a century ago. Gmelin’s lost revolution is the one from 1968, which was less a political uprising than a social revolt, exemplified to great effect by his remake of Gerd Conradt’s tracking shot of students running through the streets of West Berlin that year waving a red flag (Farbtest II, Die Rote Fahne, Colour Test II, The Red Flag, 2002). Gmelin’s father had been one of those waving the flag, and the touchstone for a series of brash paintings of a naked couple engaged in something vaguely libidinous (Film Stills, 2004) is another film from the late 1960s, this time by Gmelin’s own father, showing him practising the art of body painting with his partner.

Body painting was used as an instrument to transgress social norms and as a fast track to sexual liberation. For the ‘establishment’ it simultaneously taunted and teased with desire and distrust. Today Gmelin’s father’s near-miss sexual encounters, captured on film (de rigueur when painting bodies), register as clowning. Revolution’s sizzle has fizzled into the naughty cartoons of ‘rebellion’ spelt out on Gmelin’s canvases. He stays on-message throughout the exhibition, teasingly transporting us to the salad days of revolution west of the Iron Curtain, setting him in comfortable opposition to the comedic likes of films such as Goodbye, Lenin (2003). Hijacking revolutionary culture to ransom it to today’s mainstream is nothing if not acerbic comedy. Here’s why: in the post-Reagan era, where the United States military is larger than the next 15 largest fighting forces combined, and all evil empires are dead-enders, revolution à la GDR or à la 1968 has been restaged as a series of crushing visual gags, while being concurrently upstaged by its own offspring, whether the successful mass demonstrations of Viktor Yushchenko’s supporters against election fraud or the privatized warfare of fanatical terrorism.

In resurrecting his father’s dashed dreams only to scavenge through them, Gmelin has made things deeply personal. The artist told me that he had ‘only a vague idea’ of his father’s activities during the 1960s, which lends currency to his somewhat Oedipal curiosity and naturally charges his work with the legitimate question: ‘What did you do in the war, Daddy?’ The ends have more than justified his means; we know his father’s self-destructing revolution was never his alone (the death of one man’s dreams is a tragedy, but the death of a million men’s dreams sadly a statistic). One also wonders what his father, now deceased, might think about his son’s art, and by extension, where he would pledge his political allegiance today.

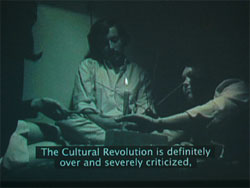

In Two Films Exchanging Soundtracks (2003) Gmelin’s scope widens, and in place of revolutionary transformation downgraded to historical re-enactment he rallies a complex style reminiscent of a double fugue, where subject and counter-subject appear simultaneously at the beginning of a composition and then are intertwined throughout. Facing each other on opposite walls are Cicilia Lindkvist’s 1972 documentary guilelessly extolling the virtues of a Maoist education and a Michael Makritsch film from 1967 venerating hashish as the open door to personal liberation. As the title promises, their sound-tracks have been swapped and the cross-over produces a range of effects, from the dark farce to happy coincidence. As college hippies in button-down Oxfords smoke dope in Makritsch’s film, the borrowed voice-over overflows with misplaced sincerity: ‘Much has changed since the Cultural Revolution. Mao’s idea of combining theory and practice is still valid.’ Both films are rooted in addiction – one in politics, the other in drugs – and now that we are all clean and sober (history decreed that we go cold turkey) we can smugly nod towards the colossal absurdity that Gmelin has cooked up as if we have all the answers.

To appreciate the depths of this absurdity it is good to know that Lindkvist’s film was originally intended as an unvarnished appreciation of corresponding anti-élitist educational systems in Sweden and China (today Swedish education ranks sixth in the world, while China is not in the top 75). Back then revolution was a one-size-fits-all suit of liberation, a collective sacrifice in the name of Utopia. Gmelin’s default message is the same as Caillebotte’s: history has always been unfaithful, and the time will come when your grandchildren will wonder how you could ever have been so naive.