Flatland

Michael Raedecker

Michael Raedecker

You never know quite where you are in Michael Raedecker's paintings. They cling to familiarity, just as their paint clings to the canvas like layers of sediment being deposited, washed away and washed back again. They are like remnants of real scenes and remembered places, fished out from the reservoir of a collective imagery and yet never quite caught, never quite fully recognisable. Much has been said of their cinematic dependencies, and while it is futile to try to identify precise mise en scènes, it is perhaps the generalised melancholy of foreign wanderers in the American landscape - the existential anomie of Wenders or Antonioni or Ang Lee - which best compares to Raedecker in tone and mood.

Raedecker paints places short in human history, and long in natural history - quite unlike Europe's increasingly utilitarian countryside, which grows ever more dense with people and construction. But their precise location - backwoods or badlands, prairie or mountain, desert or swamp - is strangely imprecise, just as their seasons are inexplicit and their temperatures indeterminate. It is a poetic imprecision which connects him historically to a genealogical tree of Dutch landscape painters - from Joachim Patenier to Hercules Seghers to Aelbert Cuyp - artists who never ventured beyond their native flatlands but who filled their canvases with imagined sunlight and impossible geologies, inspired by travellers' stories and other people's paintings of Alpine sublimity. Raedecker's paintings are similarly imagined projections of an unknown elsewhere, though here they are refracted through the prism of cinema, TV, travel brochures and 1960s or 70s lifestyle magazines.

The Dutch landscape tradition has often involved a struggle against flatness: their challenge, to dramatise unremitting horizontality within the vertical plane of the painting. In the 17th century, painters anxious to overcome the omnipresent horizon were forced to climb steeples or dunes to gain a purchase on their ground; by the 20th century, Piet Mondrian solved the problem by slowly swinging the picture plane through 90 degrees and giving us a bird's-eye view of pier and dune. Raedecker's solutions are even more eccentric. Most of the time he simply ignores the horizon, or else fails to discriminate between sky and land by rendering both in the same sludged paint. When the horizon appears, it is warped. In Mirage (1999), for example, the land is pictured as if in the aftermath of some extraordinary seismic spasm. It curves up and back in on itself like a calcified wave, parallel to its own horizon, struggling to find room for itself within the constricted rectangle of the picture. In Hollow Hill (1999), what appears initially as a worm's-eye view of the sky from inside a crater, could equally be read as a horizon line convulsed almost full circle to fit the format, with a few lone trees still clinging to their original perpendicular. If the horizon is the measure of all things, the known base around which we establish where we are, then Raedecker destabilises this surety and forces us to get lost in the tactile space of his paintings.

Unlike typical Dutch landscapists such as Hendrick Goltzius, who described the land in terms of continuous, coherent surface teeming all over with intricate detail, Raedecker's compositions oscillate between points of absolute clarity and areas of absolute sparseness. This skittling between isolated object and empty, pallid space accounts for their pervasive melancholia, their sense of barely connected loneliness. 'It's possible to give a lot of detail in a painting and still make it look empty', he says. One or two elements are picked out clearly in delicate embroidery, while all around remains inchoate matter: great marbled slurries of paint the consistency of melted ice-cream, or microscopic surface agitations, bits of fluff and hair, vermicule wriggles of paint, barely adhering to the surface. A rock, a pond, a cabin, or a weird, indelicate succulent: these understated motifs are deposited on the canvas, stranded like meteorites with their strangely matter-of-fact figuration emerging forcefully from the contrast with their formless grounds.

A recurring Raedecker scene - visible in Ins and Outs (2000), Beam (2000), or Radiate (2000) - features an isolated log cabin set in a wood of leafless trees. You can imagine a thin wind snivelling among the rotting, bald trunks, but otherwise all is cloaked in terrific silence: no birdsong penetrates the muffled, crepuscular gloom. Colour is sucked out of the scene, the palette reduced to a single muddied hue - a putty, olive, lavender, or beige. Light must be there because shadows fall, but we can't see its source; its effects are perversely vapid rather than vivifying. The ground runs liquid with mud or retches water to settle into stagnant ponds. Nature is everywhere, yet everywhere it is leaden with a sense of inertia, less landscape than nature morte. The only things imaginably alive - ivy or fungus or bacteria - live off the back of other deaths. If the landscape, as is often said, depicts a human encounter with nature, then Raedecker's meeting is the opposite of sublime. No transcendent thrill, no intimidating, life-enhancing moment, but the reversion of both man and nature to an antediluvian, pre-linguistic materialism. Like the splodge of grey ectoplasm which squeezes out of the rustic hut in his Phantom (1999), nature is as shapeless and haunting as the 'something nasty' which Aunt Ada Doom saw, but could never quite bring herself to describe, in the woodshed on Cold Comfort Farm.

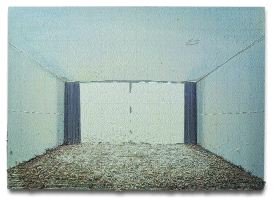

Another scene recurs, like a dream, in Raedecker's oeuvre. In paintings such as Beam (2000) and The Practise (1998), the crisp geometries of his Modernist cabins are turned inside out to describe retro-Modernist rooms with a view of far, still hills. These low-ceilinged interiors, with their insistent, exaggeratedly minimal perspectives, place us within the room and yet force us to view it from a strangely remote vantage point. They create a contradictory sense of distance and nearness, of detachment and claustrophobia. A floor-to-ceiling picture window, so appealing to Modernist American architects seeking osmosis between inside and outside, is usually the central feature. Yet, here, it is doubled within the window of the painting, and doesn't lead into transparency and liberation but a peculiar sense of vitrification, as if the rooms had been vacuum-sealed and soundproofed against emotion and experience. Spare and soft, their hessianed walls, heavy drapes and outsized bouclé rugs represent a former time's ideal decor. Now they seem forlorn, decorated only with silence and sadness; settings, perhaps, for human scenes full of misunderstanding and missed intimacy, as naggingly incomplete as a Raymond Carver short story.

What leavens the bleakness of Raedecker's uninhabited wastelands and vacant interiors is, of course, the same element which makes them sparkle as paintings: the shocking delicacy of his virtuoso needlework, set against the shocking indelicacy of the paint which threatens to soil and engulf it. Many artists have sewn as a way of democratising and domesticating the pretensions of painting, but few have contrived the combination of thread and paint, handicraft and high art, to such poetic effect. Like Fontana with his appliquéd jewels or Rauschenberg with his precious metal leaf, it is the surprising alloying of two different registers of matter and technique which makes Raedecker's art so distinctive.