Flora Whiteley

Three Belgian canaries with hunched backs and sad faces stare out like strange, pastel-coloured vultures from Flora Whiteley’s painting Parallel Lives (2014). In the background, the perfect geometry of Walter Gropius’s Bauhaus studio jars with the awkward perspective of their cage. Not that you would recognize this architectural interior unless told, but that isn’t the point. Such details aren’t meant to be decoded for their symbolism; they are simply the means of Whiteley’s very slippery and associative form of picture making.

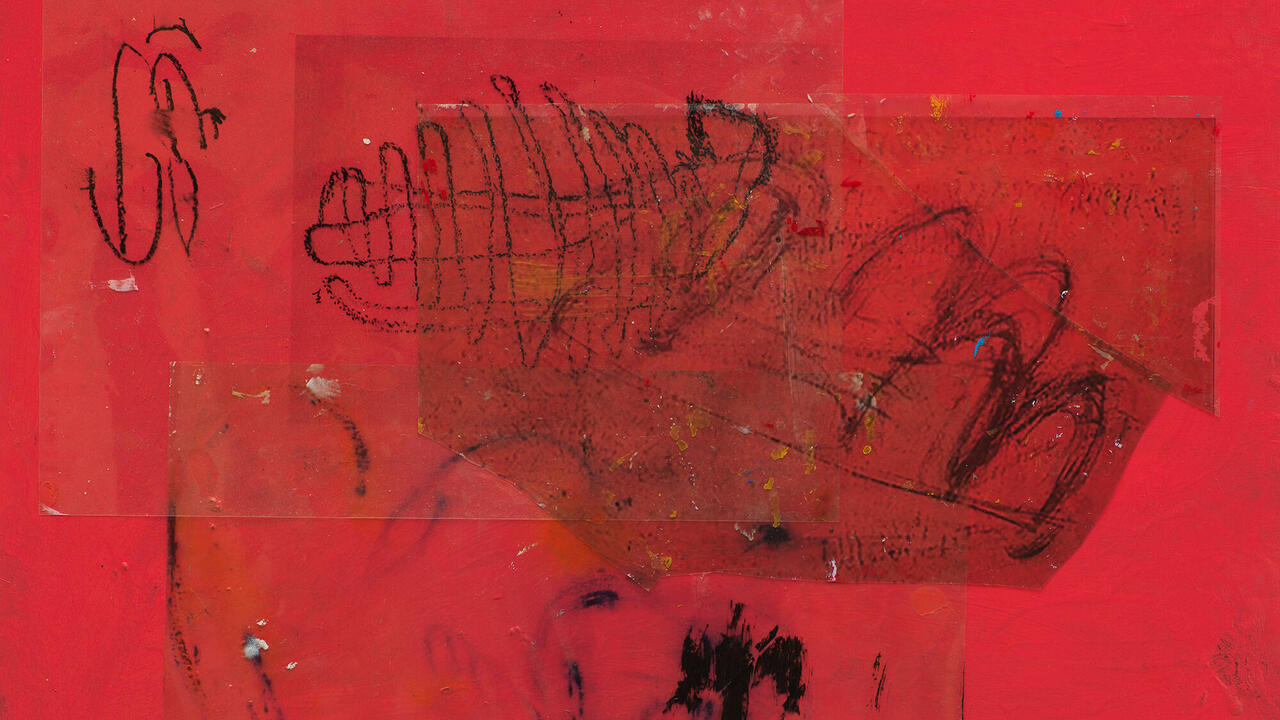

Found postcards, screen-shots from documentaries and forgotten game shows mined from YouTube provide the stages for Whiteley’s theatrical paintings. These might be populated via ornithology books, or, like many of the works here, left devoid of animals or people, so that the objects resonate

alone, suggesting the ways interiors become vessels for intimate memories or charged emotions. Whiteley’s paintings aren’t so much reminiscent of stage sets as they are the interstitial spaces of a movie: where the camera slowly lingers on a crime scene or cradle of ennui after its inhabitants have left

it or are about to re-enter. The exhibition’s title, ‘Kammerspiele’, makes clear the cinematic traits of Whiteley’s painting – referring as it does to the movement in German silent cinema that saw directors including F. W. Murnau, Carl Mayer and Georg Wilhelm Pabst producing films that focused on interior spaces. Taking their name from the theatre of Max Reinhardt, such ‘chamber dramas’ sought psychological depth in the camera’s proximity to both the actors and the individual objects under the lens.

But, again, it would be misleading to read too much into this source of inspiration; you are just as likely to meet Franz Kafka, Jean Cocteau or the Minotaur in these works. The Birthday Party (2009) depicts two girls at a table, mirrored as if on water, hands daubed with vibrant blue lines and cheeks ruddy with pink. There is something of Paul Gauguin’s hallucinatory visions here, pleasingly out of synch with contemporary trends. Whiteley’s canvases are layered, repeatedly remade, often returned to by the artist over long periods of time. In Young Cocteau (2008) this agitated, over-washed way with colour animates the scene as if it is flooded with moonlight – or transformed into the kind of electric afterimage that happens when eyes are exposed to a bright flash of light.

Whiteley used to paint all of the edges of her canvases with a neon yellow, to underscore their three-dimensionality and to give them glowing halos. The paintings here don’t have such colourings; they aren’t windows onto an imaginative world. Instead, the artist has suggested that she wants them

to step out into the world and meet you. In the centre of the first gallery this was made explicit, with the three canvases of Exit M.C. (2014) arranged to form a screen that literally divided the room. Its surface depicts the bedroom of the abandoned home of French interior designer and art patron Madeleine Castaing, who was friends with Pablo Picasso, Marc Chagall and Cocteau (characters in paintings relate throughout the exhibition like actors in a complex opera). Just as with Gropius’s empty studio, Castaing’s boudoir provides the muted presence of a fading modernism to which Whiteley seems attached. Even if it is concealed by painterly technique and buried in amongst references to the artist’s autobiography and chance findings, the early 20th century exerts a certain magnetic pull on Whiteley’s painterly production. This is not the modernism of grand utopian gestures, but the lost modernism of marginal figures such as Castaing. Exit M.C. is a clever work: a found interior – originally created by a long-dead interior designer with a rich art-historical past – turned into a painting of an interior that simultaneously produces its own interior space in the gallery. Device, representation, image and object all in one. There is a kind of echo-chamber quality to Whiteley’s painterly imagination, but also a playful engagement in a very specific type of appropriation – not the ironic, flat-handed gesture of postmodernism, but something much more subtle, literary and mnemonic, and also more elusive. It makes sense that Whiteley often uses postcards, themselves an ephemeral kind of modernity, as source: mobile, associative, embedded in different biographies, long-dead romances and now alien and unretrievable temporalities that are waiting to be found, or quietly passed over.