Formal Affairs

In recent years, abstract painting has experienced both a new popularity and a critical backlash. Can it be written off as ‘zombie formalism’ or are innovative approaches to abstraction really being developed?

In recent years, abstract painting has experienced both a new popularity and a critical backlash. Can it be written off as ‘zombie formalism’ or are innovative approaches to abstraction really being developed?

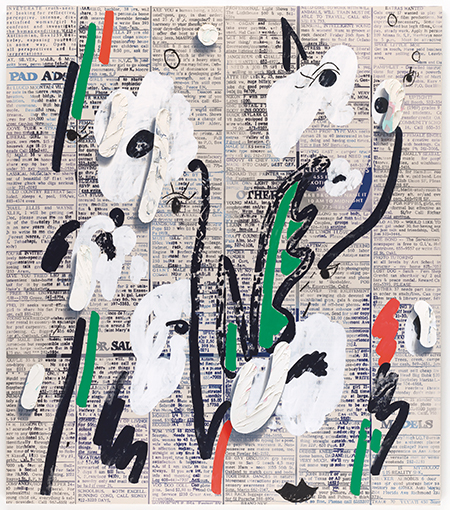

The last few years have been especially big for abstract painting, which has attracted as many impassioned advocates and opponents as it has investors. Dubbed ‘slacker abstraction’, ‘provisional painting’, ‘neo-formalism’, ‘casualism’ and ‘zombie formalism’ (as coined by artist and critic Walter Robinson), many of the works in question share an affinity for flatness, process-based approaches, improvised gestures and, at times, a playful sense of humour. Yet are all works that share these features alike? Before collapsing so much recent painting into morphological indistinction and dismissing it as solely a symptom of the market, is it possible to discern some productive, even critical, strains in today’s abstract practices? Such may be the project of ‘The Forever Now’, an exhibition of recent painting curated by Laura Hoptman at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, which brackets these and other approaches under the broad banner of ‘atemporality’. But rather than accept such generalized terms or reject abstraction as a category, how can we instead parse some particulars?

To begin, let’s look at the term ‘process’. For what unites painters as diverse as Kerstin Brätsch, Jeff Elrod, Julie Mehretu, Florian Meisenberg and David Ostrowski, among others, is an interest in process defined through gesture, and sometimes non-traditional techniques such as pouring, staining and spraying. In light of this, Hal Foster has suggested that today, like the renewed interest in performance, process acts as a guarantee of presence.1 Process assures us of the work’s unique location in place and time, of the fact that the artist is indeed present. It provides a key condition of a painting’s material value, offering an earthy defence against the perfected copy and the incursions of the digital screen.

While this rush towards the analogue by a generation of artists immersed in technology has become a critical refrain, it also manifests a diversity of responses. There are any number of artists whose work recoils into Modernist and Minimalist styles, using process to access some notion of ‘unmediated’ reality. We can also identify relational or Post-internet practices that attempt to dematerialize the art object while blurring the line between artist and audience through participation.2 Yet, there is another strain of committed studio practice that invests in process, but is polluted by language, representation and new, technologically mediated conditions of production.

Brätsch, for instance, makes ample use of traditional materials such as glass, paint and paper, but hardly is her work a simple retreat to analogue nostalgia. She is a prolific collaborator, known for opening her practice to the influences of other hands as well as techniques. Her experiments in glass employ the workshop that Sigmar Polke used for his last major public commission for the Grossmünster in Zürich, while the installation Maler, den Pinsel prüfend (Painter, Examining the Brush, 2012) recoded Brätsch’s painterly language through the media of glass and of the workshop itself, her brushstrokes preserved like flies in amber. Brätsch executes many other projects with Adele Röder as the fictional import/export company DAS INSTITUT, which polyamorously dabbles in fashion, performance, painting and advertising. Meanwhile, Brätsch’s signature painted works place glowing orbs and fan-like brushstrokes on paper installed under glass in frames suggesting large digital screens. Indeed, Brätsch has highlighted the resemblance of her marks to digitally produced brushstrokes; they are frequently overlaid on transparent sheets of Mylar, superimposed, at times, like layers in a design app or suspended like dissected corpses.

Still, while Brätsch’s work is an almost-analytic deconstruction of painterly codes, artists such as Ostrowski elevate process to the status of fetishized gesture. More precisely, whereas process was once an anti-Romantic impulse in the hands of Robert Morris, Richard Serra and others, it now occupies the very place once accorded to the unique brushstroke and narrative expression.3 To put it differently, narrative and even biography have migrated into process. This may account for the fact that, as the term ‘zombie formalism’ suggests, so many recent abstract paintings look the same; their distinction lies in the narratives of their making.4 But are such narratives, trafficked like financial instruments in our new economy, sufficient? Is it enough to know that a given painting was made by collecting rainwater, using studio detritus or by using the artist’s own anesthetized hand (Ryan Estep) or a fire extinguisher (Lucien Smith)?

If some young artists deploy process within a Minimal, architecture-friendly form of painting, just as many combine process with humour to sidestep this austerity, directing painting towards more informal and playful ends. Deployed in the service of critique, humour can also speak truth to power even when such power seems indomitable.5

The methods Meisenberg employs also involve staining the canvas, sewing into it, indexing it bodily, leaving it raw. On first glance, these formal interests might bring Meisenberg’s work closer to that of Ostrowski or Christian Rosa. But, whereas Ostrowski insists on a fetishized materialism and Rosa’s work withdraws into the nostalgia of Joan Miró or Alexander Calder, Meisenberg’s painterly gags deal with the digital detritus of phone and computer screens. Recent installations at Kasseler Kunstverein and Wentrup Gallery displayed Meisenberg’s Minimal paintings alongside flatscreens surrounded by wall graphics depicting a transparent Photoshop canvas. Meanwhile, the video You are certainly entitled to this opinion (2014) shows Meisenberg farcically interacting with the Siri function on his iPad. It is an awkward but also a much-needed reminder that technology is not total; there are still spaces of friction and play – even when interacting with the systems that seem to have colonized our lives. And while some, like Meisenberg, take a playful attitude, more prevalent is the strategy of using the formal structure of the joke. Here, contradictory associations are overlapped – language/bodily gesture, precious object/mechanical reproduction, art history/lowly medium – or else, the very authority of painting is upended by a punch line. Even in Anne Lise Coste’s work or Laura Owens’s whimsical, text-based abstractions, the set-up is always painting with a capital P – a premise then broken, deflated, secularized.

Indeed, painting still remains the institution to be demolished, preserved in its negative form, or else dispersed into architectural, and now virtual, space. If, in the 1960s, this fracture of Modernist autonomy was contentiously inaugurated by Minimalist works, today’s practices displace painting into what Helmut Draxler called its ‘apparatus’.6 As we follow this expansion of the medium into a myriad of ‘painterly’ gestures lodged in video games, film, installation and performance (recall Marina Abramović’s re-enacted performances displayed like tableaux at her 2010 MoMA exhibition ‘The Artist Is Present’), how can we even locate what painting is today? Do we evaluate it as rigorously as we would Conceptualism, as frivolously as we would entertainment or as sensitively as we would, well, painting? The most productive contemporary approaches, like Brätsch’s and Meisenberg’s, invest in experiences that are conceptually complex, sensually rich and irreducible to easy positions.

Still, as painting expands into a nebula of interdisciplinarity, a corresponding gravitational pull also collapses the work materially, conjuring up the logic of the ruin and Raphael Rubenstein’s idea of the provisional, demolished, ‘fucked up’ object that he likens to punk aesthetics.7 This logic can be traced through the work of Richard Aldrich, Matias Faldbakken, Rosy Keyser, Oscar Murillo, Kasper Sonne and others.

The ruin also informs the work of Mehretu, whose architecturally inspired paintings have customarily employed geometric forms overlaid by a dizzying tempest of pen-and-ink wash drawing. However, converging with today’s performative currents, the geometries in her recent works recede to near-invisibility, while the drawing comes to the fore as fields of hurried marks reminiscent of automatic writing or shadows of towns evaporated by nuclear testing. And while these works may recall the calligraphic experiments of Abstract Expressionism, or even those of young artists like Coste, they also retain their link to their architectural origins, attenuating this connection without severing it. In this way, they are perhaps more obligated to J.M.W. Turner than to Cy Twombly. As sombre explorations of indistinction, they depict collapse rather than perform it materially.

Of course, today’s impulse to devalue painting – to literally ruin it on stage – is not entirely misplaced, especially if one contrasts it to the rosy, anonymously produced canvases of Jeff Koons. But while such devaluation, seen most prominently in recent practices like Ostrowski’s and Murillo’s, may seem like a counter to the look of pristine commercialism, it can also exoticize formlessness and abject materials, fetishizing the real. It bears mentioning that what is often implicit in such gestures of restaging reality as distressed ruin, is the very privilege and distance belied by this act. As viewers, we get a rarified glimpse of the abjected and the forsaken – the frisson of the demolished object silhouetted by its palatial setting. If materialist critique or anti-aesthetic levelling is the objective, this gesture – seen in galleries from Bushwick to Berlin – substitutes one emphatic materialism for another. That is, it asks us to focus on the materials of the deconstructed thing rather than critically deconstruct the material conditions framing it.8

For critic Lane Relyea, rather than a form of resistance, today’s homespun production segues seamlessly with corporate-advertising strategies and the new flexible, freelance economy. Is it such a stretch to connect the raw and crafty canvases in our galleries to aesthetics that privilege the tastefully outmoded and ostentatiously handmade? Along the same continuum as our casual abstraction, Relyea argues, we can also position a new appeal to entrepreneurial spirit, where workers are increasingly individuated as ‘creatives’ yet rendered all the more exploited and precarious.9 To extend this provocative logic: in the wake of radical deregulation and the dismantling of collective labour, the aesthetics of Etsy prevail. That is, as each worker becomes equally contingent and autonomous, artistic production dons the look of small-batch, artisanal craft, complete with its modest scale, appeal to vintage patina and weathered, distressed surfaces.

Bearing all these complexities in mind, how can we then reassess painting – and abstract painting specifically – for alternative and unique modes of resistance? What inevitably comes to mind is the image of agit-prop that retools the work as political design, or the model of social practice that often forsakes the object altogether. Yet, there is another version of resistance still crucial to painters that reinvests in the object and in what we might call the latent politics of the encounter.

For Elrod, painting can gesture towards critique without abandoning itself. Forms of unmoored, immaterial labour infiltrate the field of automatist marks in his paintings, less Expressionist than redolent of computer-mouse clicks. Perfecting his computer-based technique into what he calls ‘frictionless drawing’, Elrod painstakingly masks, paints, sprays or prints the results onto canvas. His 2013 exhibition at PS1/MoMA, ‘Nobody Sees Like Us’, presented hypnotic printed canvases compiled from hundreds of computer-generated drawings created in homage to artist and poet’s Brion Gysin’s ‘dream machine’. Resembling blurred photographs of landscapes, they are sublime without lapsing into Romanticism, conceptually driven without forfeiting the visual experience of the viewer. Moreover, developed initially at his former day job, Elrod’s methods recall theorist Michel de Certeau’s notion of the perruque or a form of carving out autonomous, non-productive and playful spaces within labour. Elrod’s work thus emerges as a kind of proactive ‘making do’.10 It bears the brunt of painting’s encounter with digital technology, but also exploits this ostensible adversary for personal and artistic use.

Similarly, while Amy Sillman is known for her abstract paintings, her iPhone and iPad animations fuse abstract language with narrative and figuration; all within a practice that unmoors the painterly from its traditional auratic bases. Exhibited sometimes alongside her paintings, these pieces complete a wide-ranging practice that ultimately flattens the distinctions between abstraction, cartooning, painting and language. The young painter Alex Kwartler, meanwhile, investigates the timeworn process of fresco – a technique that demands decisive execution. His recent show, ‘A Superficial Lyric’, at Nathalie Karg Gallery in New York, juxtaposed large fresco abstractions with graphic cartoon images of a figure walking in the rain. As such, the gesture situates abstraction and illustration along the same plane. Yet while these imposing abstract works – each one humorously sealed with glossy polish – evoke blown-up details of Impressionist paintings, they also conjure large photographic prints, equal parts Andreas Gursky and Claude Monet. More critically, unlike practices that cynically evacuate the object’s affective merits under the pretext of critique, each work still communicates the artist’s investment. Here, even the cartoon images show traces of gridding, rethinking, over-painting – in a word, commitment.

Such terms may, indeed, be antiquated. However, in our culture of narrowed attention spans, cynicism and spectacle, they also become quite precious. But are the moments they designate enough? We must concede that most painters – no matter how resistant in motive – still respect the traditional distribution framework of the gallery system, the art fair and the museum, and so necessarily limit their gestures to allegory. The artist allegorizes his or her place as trapped within the art apparatus but performing for a utopian ‘outside’ where painting may recall its former powers as a public art. The problem of painting, that is, remains its uncertain place between disseminated image, object of (political) faith and luxury good.

But can we also imagine a space outside of this ambivalence? Today’s technological developments ask us to recognize inexorable shifts in art’s production, distribution and spectatorship. The challenge for us is not to recoil into formalist nostalgia or artisanal myopia, but to adapt to this arena, conceiving of new modes of production, ownership and display without losing that fragile conduit that still captivates the viewer on a level of material intimacy. And if painting alone is not up to this task, perhaps we can follow its unmoored shards into new spheres of experience, new phenomenologies of hybrid objects and new demands, but for this reason, all the more meaningful encounters.

1 Hal Foster, ‘In Praise of Actuality’, Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, Emergency (forthcoming), Verso, New York, 2015

2 For more on the connection of relational practices to a digital ‘prosumer’ model see: Claire Bishop, ‘Digital Divide: Contemporary Art and New Media’, Artforum, September 2012

3 As an ironic parallel, consider Morris’s famous essay ‘Anti-Form’ that contrasts the matter-based process of Jackson Pollock and Morris Louis to the ‘personalism’ of process that preceded it. Robert Morris, ‘Anti Form’, Continuous Project Altered Daily: The Writings of Robert Morris, MIT Press, Cambridge, 1993

4 See, for instance, Jerry Saltz, ‘Zombies on the Walls: Why Does So Much New Abstraction Look the Same?’, Vulture: http://ow.ly/HcbY0

5 We should also remember that, although humour remains a powerful weapon, it can, like the carnival, offer a temporary reprieve from domination, allowing the system to function all the more smoothly.

6 Helmut Draxler, ‘Painting as Apparatus: Twelve Theses’, Texte Zur Kunst, March 2010

7 Raphael Rubenstein, ‘Provisional Painting Parts 1 and 2’, Art in America (May 2009 and February 2012), http://ow.ly/HccuL and http://ow.ly/HccCx

8 For a closer examination of this dynamic see my postscript to ‘Neo-Modern’ in Golden Age, Christopher K. Ho and Marco Antonini (eds), Nurture Art Press, New York, 2014

9 Lane Relyea, ‘DIY Abstraction’, Wow Huh, http://ow.ly/Hcd6r

10 Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1988