Free Pussy Riot: A Report from Moscow

By putting Pussy Riot on trial, the Russian authorities inadvertantly made them a household name

By putting Pussy Riot on trial, the Russian authorities inadvertantly made them a household name

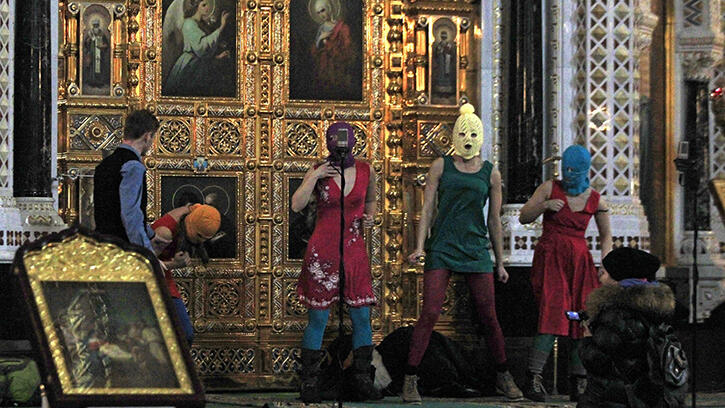

Up until the last day of the increasingly absurd trial proceedings, Pussy Riot’s supporters believed that Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, Maria Alyokhina and Katya Samutsevich would be let go or at least given a short sentence equal to the time they have already spent in jail. The sentence of two years in prison that has just been handed down has not been that surprising a result: the trio have been found guilty of hooliganism, which is punishable by up to seven years under Russian law. Still, there was nothing in the evidence that suggested damaged property, personal insults or any other actions that could be associated with hooliganism. The ‘punk sermon’ they delivered in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour wasn't even against the believers: its refrain of ‘Virgin Mary, dispose of Putin’ suggested a modern-day prayer.

It is safe to say that the trial has made Pussy Riot a household name, in Russia and abroad. Tolokonnikova acknowledged as much in her interview with the liberal New Gazette: ‘We couldn’t even think that authorities would be ridiculous and stupid enough to persecute and thus legalize anti-Putin feminist punks in the social field.’ Without the exposure of the trial, they may well have been ignored by those who felt uneasy about their intrusions on to sacred ground – and there are a lot of current Pussy Riot supporters who were repulsed at first by the fact that they chose a functioning church to voice their agenda. If they had enjoyed their freedom after the incident, there would have been no discussions of whether or not the “punk sermon” was art – a question that is even more pressing now that Pussy Riot have been nominated for Russia’s answer to the Turner Prize – the Kandinsky Prize. No trial also would have meant no battles about the degree of actual feminism in their actions.

But the arguments for or against the actual performance, however eloquent they were, took second stage to the fact that its performers were criminally prosecuted. The trial was about the trial. It became the focus of political and social frustrations. Three young girls raging against the state machine and losing: it embodies exactly how the opposition felt after the elections in December 2011 and March 2012 – a revolt of the colourful underground against the tedium of a conservative, predictable, and at times violent social reality. Left-leaning theorist and artist Anatoly Osmolovsky, himself a veteran of 1990s activism, has compared Pussy Riot to Abstract Expressionist colour field paintings – alive and kicking against a monochrome background of apathy.

The last day of the trial saw an unprecedented surge of creativity among Pussy Riot’s supporters. They put balaclavas on monuments to Alexander Pushkin, defaced ads with faces of Russian pop stars, and started internet memes, the most memorable of which was a map of Russia with the neologism ‘Pussia’ written all over it. It is also a conflict of West vs. East: Paul McCartney, Anthony Kiedis, Madonna, Bjork, Yoko Ono, and numerous musicians around the world have expressed their support for Pussy Riot. Meanwhile, most local Russian pop stars (with one or two exceptions), who cater to a wide audience of low income, largely uneducated audiences, supported the court’s decision. This audience is no small chunk of Russia’s population. A survey by sociologists from Russia’s Levada Center showed that 44% of Russian citizens thought the trial was objective, while only 17% questioned the partiality of the court.

Many Pussy Riot supporters believe that the court’s decision has been part of Vladimir Putin’s personal vendetta; others think that Russia’s Patriarch, Kirill I of Moscow, was behind the severe indictment. Thus they see the court’s decision as Putin or Kirill’s defeat. ‘Authorities smacked the football into their own goals’, wrote writer and radical politician Eduard Limonov in his LiveJournal blog. The Church seems to understand the vulnerable position they have been put in by the court’s decision: mere hours after the indictment it published a press release calling for Pussy Riot’s pardon while still condemning the action. Putin had also advised the court not to be too severe. Both statements have been interpreted as hypocritical by Pussy Riot supporters on the grounds that the trial should have never started in the first place.

The fact that the performance was done in a church, however, made the trial all but unavoidable. Since the 1990s, artists and curators could virtually do what they wanted with one exception: they could not make statements against the Orthodox Church. In 1999, Russian artist Avdey Ter-Oganian enacted a performance during which he destroyed religious icons with an axe as part of his ‘Avant-garde School’ series. The negative reaction was so severe that he had to flee the country or face jail time. In 2007, right-wing activists sued curators Andrey Erofeev and Yury Samodurov for their show ‘Forbidden Art’, which, according to the prosecutors, contained art works that offended believers. I served as one of the experts for the defense during the ‘Forbidden Art’ trial, aiming to explain to the court that SOTSARTist Alexander Kosolapov’s depiction of Christ on a Coca-Cola ad with the slogan ‘This is my blood’ (This is My Blood, 2001) was, of all things, anti-American, not anti-Christian. Mine and other experts’ statements did not convince the court, which made Erofeev and Samodurov pay a large fee.

The church in Russia enjoys a unique position outside of history. It is still viewed as a victim of Soviet repression, even if today pastors have a much larger and state-approved influence on society. Its interiors and sacred artefacts derive from an unchangeable canon and cannot be altered in any way. This position has made it a lot easier to invest political weight in every case that is connected to the church, because the intruders are wrong by default. Authorities therefore can start from this fact and go further to show that – in most instances – the fake enemies of the church are also enemies of reason, stability and the country itself. If they are tampering with values that an increasingly materialist and egotistical post-Soviet society holds dear, then they have no values whatsoever and should be treated as enemies of the people. This line of thought is not uncommon in the West (see the Smithsonian Institute’s censorship of David Wojnarowicz in 2010), but far less severe.

Still, protests against the court’s decision are flooding the media as you read this. They come from different sides of the political and social spectrum, and this confirms one important fact: People may or may not be offended by what the girls have done; they can think them foolish or the church repressive. But all of them unanimously have no faith in the Russian court, an institution that time and time again proves itself too flexible to political or financial pressure. The trial, as I said, is about the trial. To let them go is to show that justice exists, simple as that.

‘Putin starts the fire of revolution’, a new single by Pussy Riot, presented on the last day of the trial, can be heard here.