The Busan Biennale is Port Facing

From Chinatown to the Jagalchi fish market, the 2024 edition maps the landscape and hidden histories of the maritime city

From Chinatown to the Jagalchi fish market, the 2024 edition maps the landscape and hidden histories of the maritime city

When summer arrived, I often used to visit Busan, where I encountered a bustling port with stacks of building-sized shipping containers, a briny fish market filled with lively chatter, and beach tents lining the hot sands of Haeundae. The city revealed its true self after sunset, with the lights of fishing boats twinkling on the horizon and tourists mingling with locals, sitting in small groups under the beach lights, engaged in lively conversation. Busan has always held a special appeal for me with its sense of ‘aliveness.’

The title of this year’s Busan Biennale, an event initiated by local artists in 1981, is ‘Seeing in the Dark’. During the European Enlightenment, visibility and light were equated with knowledge, while darkness was something to be dispelled. This Biennale’s co-curators, Vera Mey and Philippe Pirotte, challenge this belief, presenting darkness as a space for an inclusive, alternative history.

Recalling their research trip from Busan to Fukuoka, Mey explains, ‘Busan is a port city. It has a long history of trade and the movement of different peoples, making it quite unique within Korea. This diversity is seen in places like Chinatown, where signage for Russian and Kazakh communities can be found. We were interested in this idea of “pirate enlightenment” to think about different communities that are often socially or politically excluded from normative lives.’

Pirate enlightenment, a notion from American anthropologist David Graeber, revisits the early autonomous societies of pirates, untouched by government or large capital, and mostly existing in the shadows. The co-curators note their distinctive decision-making process as one of the conceptual foundations, referencing the idea of a council of the best pirates, selected regardless of cultural background or skin colour.

In addition, Busan’s role as ‘a route for the spread of Buddhism to Japan’, as Mey describes it, introduces another curatorial axis: the way of Buddhist monks. In an alternative community, monks regularly make collective decisions on monastic rules and communal property, finding themselves as a ‘self without place.’ This metaphoric self can be the migrant, the refugee, the proletarian rebel, the drop-out, or the pirate. Busan is a meeting point of these two apparently antithetical ideas – piracy and Buddhism – finding harmony and illumination in their darkness.

So, how did Mey and Pirotte approach the city? To continue Busan’s legacy of diversity, their Biennale introduces artists rarely seen in Korea, such as John Vea from Auckland and Tracy Naa Koshie Thompson from Ghana. Local artists such as monk Song Cheon, who has practised traditional Buddhist art for decades at Tongdosa Temple, add local flavour.

Besides the main venue at the Museum of Contemporary Art Busan, exhibition spaces across the city were chosen to capture the full breadth of city life. Here are some of the venues that inspired the curatorial team, to give a sense of the scope and spirit of the Biennale and the true character of Busan after night falls.

Choryang House (117-8 Choryangsang-ro, Dong-gu, Busan)

Choryang, the old name of the neighbourhood where Busan station is located, means ‘the path through the grassy field’. As a crucial crossroads between sea and land, what was once fields became the centre of the Japanese community, serving as a trading post during the Joseon Dynasty, and was later transformed into Busan station. The two-story Choryang House, situated in the foothills behind the station, was built in the 1960s, a Western-style home resembling a ship that invites us to imagine its former owner’s possible involvement in the city’s dominant industry. This striking building has been transformed into a gallery space for the first time for this year’s edition.

Beomeosa (250 Beomeosa-ro, Geumjeong-gu, Busan)

The myth of the Nirvana Fish at this temple captivated Mey and Pirotte when they were researching the history of local temples and guided their curatorial discourse on the way of life of Buddhist monks. According to a 16th-century geographical study, the name Geumjeongsan (Golden Well Mountain) comes from a golden fish that descended from the sky and swam in a well, leading to the establishment of the temple. Despite numerous fires and restorations, the 7th-century remnants within the three-story stone pagoda and the temple’s foundations still reflect Busan’s significance in Buddhist history.

Youngju Mansion (#5, B1, 9-Da-dong 51 Yeongcho-gil, Jung-gu, Busan)

Youngju Mansion is reached via a winding hillside road. This 350-square-foot art space sits in the basement of an old apartment building from the late 1960s, part of a postwar public housing project. In 2008, three female artists/curators revitalised it as a space to introduce underrepresented artists. Mey was intrigued not only by its programme’s focus on personal and micro-histories but by the location. In Busan, hills with views of the port have traditionally been home to blue-collar workers and new migrants, watching for incoming ships in order to rush down to the harbour to find work. We were interested,’ says Mey, ‘in how the idea of perspective and seeing relates to looking at art and considering workers’ histories in the city.’

Jagalchi Fish Market (52 Jagalchihaean-ro, Jung-gu, Busan)

When asked about the most memorable restaurant she had come across in Busan, Mey answered without hesitation: ‘Eating at the fish markets and seeing the lives of everyday Busan people was very inspiring.’ Today home to more than 500 thriving units, Jagalchi Fish Market began following Korea’s independence, when refugees set up street stalls to sell their catches. You can select seasonal seafood and eat it raw on the spot, with local vendors selling their goods on makeshift wooden boards, just as they did in the past.

Chinatown

Chinatown’s long history dates back to the 19th-century Qing Dynasty and the area developed as more Chinese immigrants moved there during the Japanese colonial period in the first half of the 20th century. Once home to the Chinese Consulate, the area has diversified over the past decades, as the Chinese community has gradually relocated to other regions, and now includes immigrants from Russia and Kazakhstan. With its lanterns and central arch, different regional cuisines and street names in various Central Asian languages, it is reminiscent of an ancient Chinese city (visit Jang Seong Hyang, where the protagonist of Park Chan-wook’s 2003 film Oldboy eats dumplings). If anywhere in Busan tells us that foreigners are no longer strangers, it is Chinatown.

This article first appeared in Frieze Week, Seoul 2024 under the title ‘Ports of Entry.’

Further Information

Frieze Seoul, COEX, 4 – 7 September 2024.

Limited tickets for Frieze Seoul are now on sale – don’t miss out, buy yours now. Alternatively, become a member to enjoy premier access, multi-day entry, exclusive guided tours and more.

A dedicated online Frieze Viewing Room opens in the week before the fair, offering audiences a first look at the presentations and the ability to engage with the fair remotely.

For all the latest news from Frieze, sign up to the newsletter at frieze.com, and follow @friezeofficial on Instagram, X and Frieze Official on Facebook.

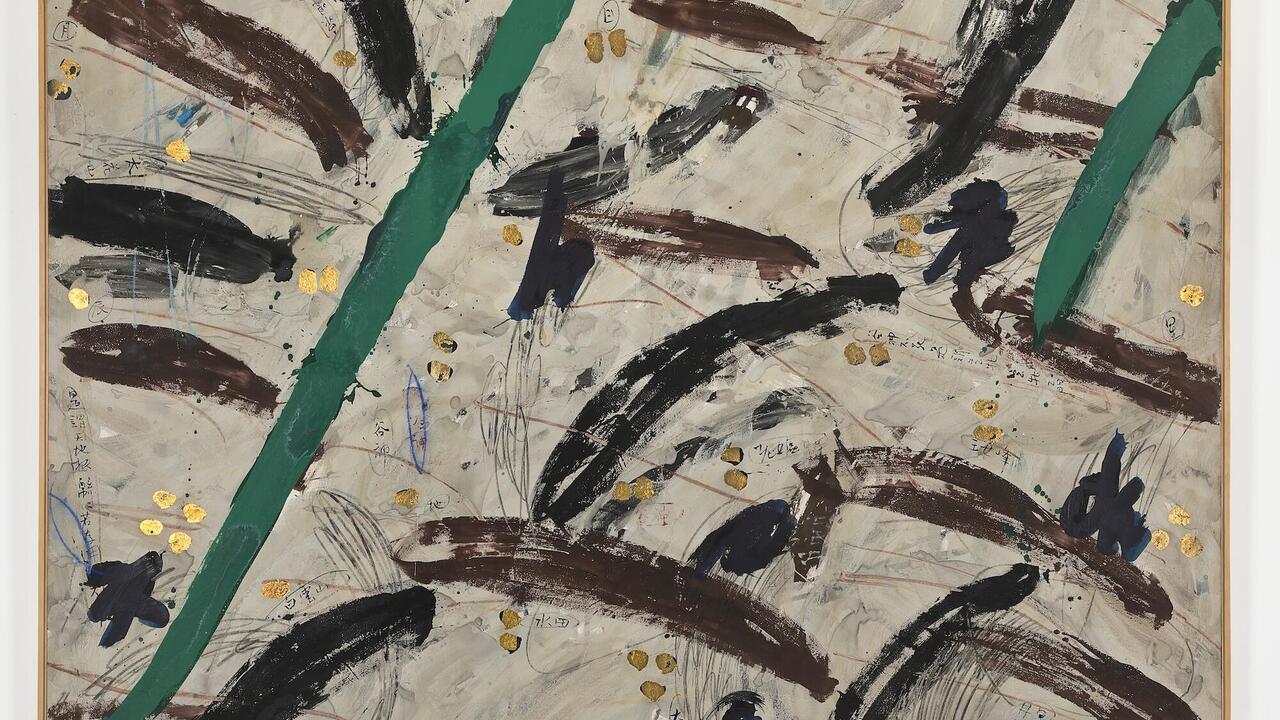

Main image: Bang Jeong-A, America, his unwavering attitude, 2021. Courtesy: Busan Biennale