Geta Brătescu

Galerie Barbara Weiss

Galerie Barbara Weiss

Geta Brătescu, the current doyenne of Romanian contemporary art, was born in Ploieşti, near Bucharest, in 1926. Brătescu worked mainly as a graphic designer before graduating in humanities and fine arts in 1971. The 1970s was the decade in which Romania attained a certain measure of governmental autonomy, distancing itself from Soviet influence and implementing its own version of state socialism. No longer bound to the canon of Socialist Realism, Romanian artists – at least ones who had not fallen out of favour – carved a quasi-autonomous cultural niche for themselves. Abstract art, hardly suitable for unequivocal political subversion, became an officially tolerated if not readily accepted genre. Unsurprisingly, the decade was to become Brătescu’s most prolific, the one in which her graphic practices expanded into performance, textile work, and object-based assemblage.

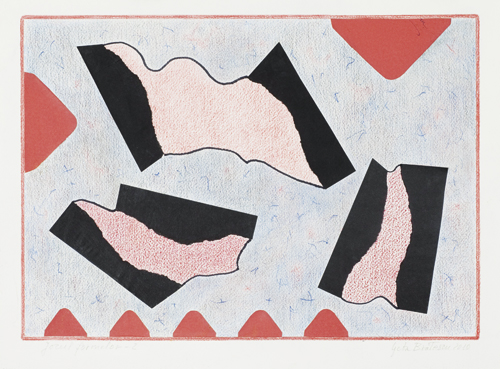

Atelier Continuu, Brătescu’s recent exhibition at Galerie Barbara Weiss, grouped together a heterogeneous body of work and took the 1970s as its starting point – here represented by Typography (1974) one of Brătescu’s most iconic works and the exhibition’s centrepiece. At the entrance of the exhibition space was The Strangers (2007), and the wall piece Untitled (1987–88) which spilled onto the floor in earthy hues. Himere (2005), a series of drawings executed with closed eyes, asserts the artist’s lifelong fascination with fabular anthropomorphic objects and animals.

Typography (1974), a series of four black and white photographs of industrial printing press parts was shown together with a semi-folded sprawl of molleton fabric: refuse originally found on the printing workshop’s floor, reconstructed from the artist’s sketches for the present exhibition. This piece was originally exhibited – in slightly different form – at Galeria Nouă, Bucharest, in 1974, where, together with gallery director Anca Arghir, Brătescu invited the printing press operators to the opening, only to be later accused of proletcultism (cult of the proletariat), according to Arghir. The event nearly coincided with Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ performances, in which she collaborated with the Whitney Museum’s maintenance staff in New York (I Make Maintenance Art One Hour Every Day, 1976), but rather than attempting to engage with the social conditions behind artistic production, Typography points to the intersection between the organic and the mechanical found in obsolete objects.

There is a lacuna in the Western reception of so-called Eastern European art: authenticity is granted largely to artists sharing Western references. Though it might be tempting to describe Brătescu’s oeuvre from the standpoint of feminism or performance, this approach risks losing sight of the artist’s historical singularity. Brătescu’s interest in the staging of the self, prosthetics and partial objects is not a militant manifesto aimed at deconstructing the male gaze. It attempts, rather, to engineer contingency, which can perhaps provide us with the key to understanding the continuity between the artist’s textual and visual works. Whilst drawing invariably takes precedence, Brătescu’s strokes are always storied, engaging elements of myth or literary sources in frantic, automated expression. Pairing the charcoal drawings Pre-Medeic Drawings (Form-Inform) (1975–78) with Labyrinth (1992), a mesh of paper threads and wood splinter, Atelier Continuu charts the oscillation between narrative and trait in Brătescu’s oeuvre, foregrounding gesture and staging a universe turned inward.