Influences: Geta Brătescu

For more than four decades, Geta Brătescu has been a central figure in Romanian art. She writes about the images, travels and art works that have influenced her practice

For more than four decades, Geta Brătescu has been a central figure in Romanian art. She writes about the images, travels and art works that have influenced her practice

I have been influenced by the authority of art. Everything that I’ve seen in museums or cathedrals on my travels – in Italy, Greece, Germany, France, the UK and Denmark – has had an impact on me through the incontrovertible truth of its imagery. In other words, a drawing (whose authority lies in the drawing) cannot be contradicted.

1. My travels with my husband. Our car, a Fiat 1300, took us everywhere; it was our hotel and our restaurant. We were ‘like gypsies’, as someone said to us. Yes, we travelled like gypsies, particularly as our routes followed the map of art’s sacred sites. Our journeys were pilgrimages, and it was possible for them to be so because of love. As time passed, and I viewed art works throughout history, my moments of total admiration were manifold. I concluded that there were no ages and places more important than other ages and places, as long as art flourished there. I would be hard-pressed to choose a single piece as an example. Think of the African art that inspired Europe. How can one choose?

2. The crucifix with the figure of Christ is a hallowed object, not least because of the dramatic composition of the whole piece. The body of Christ is not an exercise in anatomy, although the anatomy has been respected on many occasions. But the concept of the crucifix is always the same; Christ’s form always has a special character that is preserved in all the sculptures of the crucifix from northwest Europe. What I learned from this representation is that art requires awareness, rigour – it demands a sense of space. Visual art is a dialogue with space, whatever you do.

3. My travels in Italy. While on a trip to Italy in January 1966, I wrote: ‘Venice is a desolate scene. Modern man with his simple attire and easy manner passes by unnoticed on this canvas suited to brocade and ritual gestures […] Vesuvius stands placidly with its bevelled summit. Vegetation and flocks of animals rise along its back. On its thick crust, even on its slopes, man has planted his home, like the roots of trees. The air, like gentle breaths, seems to give rhythm to the chest of this tranquil scene of nature. In it, and ignored by it, the ruins of the ancient city preserve the pattern of life that once thrived here. The tranquil presence of the volcano engages the whole community; all around it, caressed by the sweet climate, things, through their mere existence, speak of life and death.’ (Extract from Brătescu’s untranslated book De la Veneţia la Veneţia, From Venice to Venice, 1970)

4. Edgar Degas was a great draughtsman: his drawing forms the basis of his painting; it is the skeleton on which his art is hung. As he said: ‘Drawing is not form; it is a way of seeing form.’

5. Charles Rennie Mackintosh was born, lived and worked – for the greater and most important part of his life – in Glasgow. There, he created a new style. Together with his wife Margaret Macdonald and a few other artists, he established a trend that reached as far as Germany and Austria, and his influence was so great that the stylistic avant-garde at the turn of the century was sometimes known by the name of ‘Mackintoshism’. The Hunterian Art Gallery of the University of Glasgow displays the ‘Mackintosh House and Collection’: a reconstruction of four rooms from what had been Mackintosh’s house. The furniture and décor – all original (if perhaps overly restored) – made up part of the artist’s personal collection. They are set out just as they were in his residence at 78 Southpark Avenue, where the Mackintoshes lived for eight years until 1914, when, feeling that they were on the wane, they left the city. The Hunterian Art Gallery’s graphics studio also preserves more than 600 of Mackintosh’s drawings, watercolours and designs. I once rummaged through several cases. His graphic art, while austere and sometimes precise, almost plan-like, always preserves imaginary suspension points; it is always saying, ‘And you can go on even further from here. Think. Dream.’

I remember a small drawing, in pencil with white highlights, bringing together on one finely drawn line three or four solutions for a chair with a very high back. The light touch of the drawing, the economy of expression, encouraged invention, as music sometimes does, where one melody can stimulate countless and surprising variations. The subject, which is the function of the chair (as a structure and not as an ornament), in itself produces the field of poetry. And thus in Mackintosh we perceive a ‘sculptor’, just as, watching the series of birds that must go higher, in Constantin Brancusi we make out a ‘designer’. This process of drawing nearer is a neat illustration of the sense of renewal that marked the early decades of our century, the bonding between industrial arts and art. (Extract from Brătescu’s travel journal, 1985)

6. Romanian folk art. The primary shapes in Romanian popular art are geometric: the circle and the square. The exhibition ‘Croilul Romanesc’ (Romanian Peasant Costumes), held in 1974 at the Museum of Popular Art in Bucharest, gave me the idea of drapery as a suggestion of architecture. Thus, this ‘Transylvanian Shirt’ became, through its intrinsic functional structure, the premise for my drawing Barn with Baking Industry (1974). That drawing and the image of the Transylvanian shirt were shown together in the 1980 Drawing Biennial in Pécs, Romania.

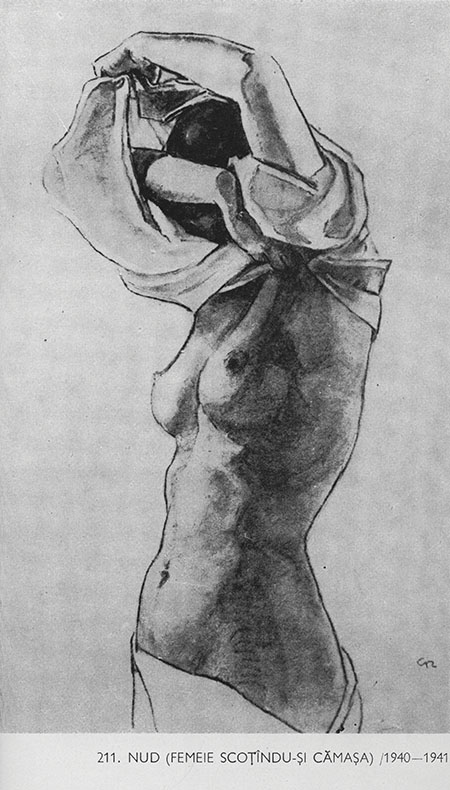

7. My teacher Camil Ressu. For me, school was a landmark; Ressu was an exceptional draughtsman as well as being at the peak of his painting career, and was therefore an excellent teacher. He had a sense of space. His revisions of sketches of nude models were conditioned by the position of the silhouette on the space of the paper. The most important thing for him was that the model, whether seated or standing, had to form an object perfectly balanced in space.

The doctrine put forward by Ressu is so elementary that it functions as a master key, opening every door. Through his intense strictness, Ressu gave us immense freedom. The model with whom he was working was both architecture and living being – an abstract female with the stateliness of a monolith and a fertile body, but not in a carnal sense. She was an impermeable anatomical building around which space would become a recipient. Ressu did not demand manual dexterity from the draughtsman; he did not champion the ‘sensitive’, ‘cursive’, ‘investigative’ or ‘beautiful’ line. He sought a meaningful connection with the structure of the object. You had to feel how a plane is attached to the surface of the dais, how one shape ends and another starts, how the whole thing balances or is unbalanced on the joints of its axes. His discussions concerning the human body’s state of equilibrium in space reawakened a primordial experience. That is why his lessons are fixed in my memory with a degree of pathos. In the spirit of my drawing I linger on the artist Ressu and hold on to him, in that same spirit, as my teacher.

8. The fresco at the Villa of the Mysteries, Pompeii, represents, through its style, that branch of ancient art that fosters a close link between sculpture and architecture. People and objects coloured in shades of ochre, interspersed with violet and brown, stand out against the red background; they are grouped according to a succession of ritual moments, but held together by the unity of colour and cursive style. Forms (which take their shape from the subtle value gradation) rise like statues on the continuous horizontal from where the fresco begins. Having been conceived that way, the fresco is reminiscent (not to detract from the style of painting) of narrative bas-relief friezes. (Extract from Brătescu’s From Venice to Venice, 1970)

Translated from the Romanian by Christopher Hughes

At the age of 86, Brătescu still works in her studio every day. Selections from 'The Rule of the Circle, The Rule of the Game' (1985) were shown alongside two of her videos at this year's Triennale in Paris, France. A major survey of her work is currently on view at Salonul de Projecte in Bucharest until the end of the year. Brătescu's work will also be included in 'A Bigger Splash: Painting after Performance' at Tate Modern, London, UK, from 14 November 2012 to 1 April 2013, and she will be participating in the 'Memory Marathon' at the Serpentine Gallery, London, on 13 and 14 October.

Main image: Geta Brătescu, Self Portrait with Bird 2, 1985, graphite on paper, 30 x 63 cm.