Global Village I

Switzerland’s schizoid relationship to internationalism and isolationism

Switzerland’s schizoid relationship to internationalism and isolationism

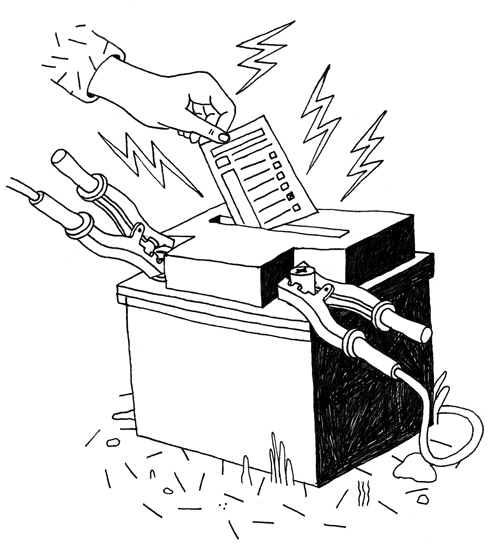

The passing of new immigration restrictions by referendum in Switzerland this past February was a shock not only for the country’s political establishment, but also for its creative class. To the rest of the world, Switzerland is a global centre with a view of the Alps: Zurich’s Paradeplatz, the World Economic Forum in Davos, the United Nations Office in Geneva, and Art Basel. At first glance, it’s inconceivable why Switzerland, so proud of its prosperity, sophistication and international connectedness, would suddenly and drastically limit the hitherto unrestricted entry of EU immigrants.

What kind of devil forced the dear old Swiss to put such a brutal end to their successful model of international openness? The return of a suppressed xenophobia? A symbolic protest vote that got out of hand?

Both factors surely played a role, and xenophobia continues to rear its head in the extremely charged atmosphere that has dominated Swiss politics since referendum day. National conservatism is triumphing, kept on a tight leash by multi-billionaire politician and ‘voice of the people’ Christoph Blocher. The vote is seen as a sea change. Unfortunately, lost in today’s political din is that the reasons against mass immigration were wide-ranging and that the outcome of the vote was far less surprising than the snubbed European public would like to believe.

The underlying problem can be attributed to a simple truism: Switzerland suffers from severe schizophrenia when it comes to its relationship with the rest of the world. On the one hand, it’s one of the world’s most globalized countries; on the other, it continues to view itself as an island of prosperity, as an exception, as an alpine fortress. It is home to powerful multinational corporations, yet quite consciously maintains its defiantly insular conception of self. No other country has profited from globalization quite as much as Switzerland, yet it simultaneously views the outside world as a threat against which it must seal itself off. Switzerland’s identity is torn between land of Heidi and centre of international trade.

In other industrialized nations, the distortions that accompany globalization catalyzed a nostalgic countermovement meant to preserve national identity. But in Switzerland, the symptoms of this polarization are more severe. The opposing powers of internationalism and isolationism have always been in fragile balance in Switzerland, a country that vis-à-vis Europe has always insisted on special status, refusing to join either the EU or its predecessor the European Economic Community. What was once a fragile balance today seems to be going terminally off-kilter. How Switzerland is to redefine its relationship with the rest of Europe, a successful one until now, remains entirely unclear.

In the 20th century, the Swiss confederation rose from a resource-poor agrarian state to one of the most prosperous countries in the world because, among other reasons, it managed to survive two world wars unscathed, keeping out of the continent’s biggest catastrophes with deftness and a good dose of ruthlessness. For the majority of the Swiss, it’s irrefutable gospel that isolation is the safest path for a small state to protect its own interests. This tenet continues to be the basis for the glorification of Swiss ‘neutrality’ which, though unctuously dressed up as pious virtue, is by the same breath the legitimacy for offering the best business opportunities. Not for nothing do contemporary politicians of the right-wing populist SVP compare Switzerland’s position today with the situation when it was threatened on all sides by Hitler’s Reich. The average European, EU-sceptic or not, understands crystal clear that the European Union was founded to protect against another world war. Swiss national mythology – however implicitly and veiled – counters that the EU is nothing but the successor to the Nazi Reich.

Of course speculations of this type have little to do with reality. More than half of Swiss exports are EU-bound. Nearly one sixth of Switzerland’s residents possess an EU passport. The steady stream of immigration – in Europe second only to rates in Luxembourg – inevitably has a slew of negative consequences. But there is practically no other European country poised to solve its ‘immigrant problem’ as smoothly as Switzerland. The unemployment rate is at a shrinking three per cent and minimum wage is disproportionately high compared to that of other countries. Crime rates remain extremely low. In contrast to their European neighbours, the Swiss continue to live in utopian conditions.

On top of all this, the positive effects of immigrant labour are striking: the Swiss economy’s development continues to be extremely dynamic. Under the current circumstances of the global market, this is not a given. The majority of Swiss citizens, however, seem blind to the facts. The historical instinct to withdraw has been taken too far – beyond the pragmatism of border policy. In Switzerland, whether it’s despite or because of the country’s high immigration rates, chronic ambivalence towards everything cosmopolitan is discernible in all aspects of daily life.

Take Zurich, for example, the nation’s metropolis and most important economic centre. Zurich should theoretically be the most cosmopolitan city in German-speaking Europe, considering the city’s hard-hitting finance industry, its 30-plus per cent rate of foreigners, its German and American business managers and bankers, and its countless international schools. And yet even Zurich cannot escape the classic Swiss symptoms of a contrived and assertive provincialism.

It starts with the fact that Zurich has developed only a limited urban culture. In the 1970s, writer Paul Nizon quipped that Swiss cities were befallen to an obsessive-compulsive Verdorfung, ‘villagization’. Architecture is only begrudgingly ceded a representative role in the urban landscape. Switzerland’s agrarian roots and lack of courtly residences still resonate in today’s urban planning projects. Even in Zurich, ambitious and progressive architectural projects are reliably blocked by public vote. Neither a new football stadium nor a new state headquarters met with approval at the ballot box. The ‘Nail House’ – a joint project by Thomas Demand and architects Caruso St. John – also perished at the hands of a public vote, even though Zurich would have been able to secure a new landmark building for very little money. All manifestations of the urban are perceived with the greatest mistrust. It’s impossible for a truly cosmopolitan culture to develop under circumstances like these. Bank vaults and organizational charts can be international in Switzerland but not a city’s appearance. Not public life.

Another symptom of this insularity is visible in Zurich’s social scenes. Statistically speaking, the city is home to many foreigners who hold important positions. But socially, they live in a parallel universe. Expats have their own schools, their own bars, their own neighbourhoods. Unlike in ‘real’ big cities, fluidity among communities in Zurich is extremely limited. Even the art scene, which contributes significantly to the cultural atmosphere with its numerous international galleries and institutional clusters, like the Löwenbräu Areal, have a sort of extraterritorial status. Zurich has a surprisingly vital art scene – but interactions with its local surroundings are limited.

The vote against immigration reopened this fissure in Swiss identity. Its roots run deep into the nation’s political, social, and cultural foundations. Ultimately, pragmatism will prevail. But it will not heal the schizophrenia.

Translated by Yana Vierboom