The Great Escape

Childrens Books

Childrens Books

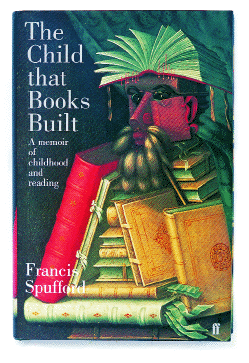

Dominating the opening chapter of Francis Spufford's previous publication, I May Be Some Time: Ice and the English Imagination (1996), is the image of a small girl, book in hand, in retreat between window and curtain. Jane Eyre is using imagination to 'outbid actuality', the memorable misery of Aunt Reed's ghastly household. Her book allows her to create an alternative space that can relieve the almost unbearable 'pressure' of reality. This is the early bargain Spufford makes with his reading matter in his latest, and highly original, exploration of another kind of geographical imaginary, The Child That Books Built, A memoir of childhood and reading (2002).

The Child That Books Built is about the germination of the reading habit and the compulsion to take in available text, a simple addiction to print. (In this book Jane Eyre does not appear until the final chapter - the prototype of a further threshold, that between children's books and adult literature.) Anyone haunted by efforts to read through a school lunch break or who still finds some form of the printed word a necessary accompaniment to banal activities such as teeth-cleaning will feel the thrill of recognition of a fellow obsessive. Most importantly, this volume speaks to those for whom books still maintain 'the primary association with comfort that is laid down by childhood reading'. Spufford evokes that prelapsarian critical state enjoyable when the notion of a transparent text is not just a possibility but is taken for granted.

The specific addiction is, of course, to narrative. Reading in childhood is invariably a form of travel, a way of exploring other places, other worlds. Spufford describes his reading habit evolving as a response to an intolerable external situation - in his case, a sister dying slowly but not always surely from 'a ridiculously rare disease'. But do 'bookish' children read obsessively only because there is something they need to escape from, or does the appetite for fiction develop because they have found a place to escape to? The world often condemns those deemed 'bookworms' as social inadequates, incapable of dealing with reality. As a child who spent at least as much time with fictional companions as flesh-and-blood friends, I was certainly treated as eccentric. In some ways Spufford's memoir shores up that stereotype, as he describes the exquisite hit of the deal that allowed him to turn away from family life, to find an equilibrium through a 'piped experience pressing back the world'.

Yet in his juxtapositions of readings remembered from childhood and researched adult re-readings he rescues, perhaps inadvertently, the very reverse of that proposition. These reunions, which will ignite the Puffin-administered memories of many readers now in their 30s or 40s, celebrate the wonderful fact that so many of the works that fuelled Spufford's addiction remain seriously worth reading. Analysing the specific power of these novels gives escapism a different spin. You go to another country, another world, not because of what you are leaving behind but because of what that other world offers. As Spufford demonstrates rather brilliantly, different kinds of books offer not just alternative scenery or inhabitants but different ways of being.

The ludicrous current success of the Harry Potter novels among grown-ups may well be due to the fact that they allow the pleasure of regression to childhood reading without the possibility of disappointment. A format can be returned to, while specific memories rest undisturbed. There is none of that awkwardness of re-meeting a long-lost friend, none of the sudden clouding over that makes you see the window rather than the view. You can avoid the heartbreak of tracking down a book read repeatedly as a child (perhaps to read aloud to your own children), only to find that it now comes across as trite, coy or politically unpalatable.

This does not apply to Spufford's most detailed revisiting, which maps his own reading progress in a kind of developmental geography. Having explored the forest of early childhood (the wild wood of read-aloud fairy tales and picture books) and stepped on to the island of fantasy (Narnia obviously dominates), we reach the town, a staging post that is both real and metaphorical. Welcome to De Smet, South Dakota. De Smet was the end of the road for Laura Ingalls Wilder and the 'Little House' books (1932-43), and it is the place Spufford uses to illustrate the subtle interactions between fiction and life.

It's an inspired choice, partly because one of the features of the series is the way in which the books grow up with both child heroine and reader. The simple life of five-year-old Laura in her 'Little House' in the Wisconsin woods is told with a simplicity that imprints itself on the imagination of the youngest of readers. (I can still remember trying to make butter, like Ma, coloured yellow in winter with carrot gratings, as I can still remember insisting on buying a fully furred rabbit from the butcher simply in order to skin it, in homage to Arthur Ransome's Picts and Martyrs, 1943.) By the fifth book in the series, The Long Winter (1940), life and fiction have become immeasurably more complicated. Both Laura and her readers are now learning to deal with other people. The necessary, almost invisible, decisions involved in such interactions are also the choices involved in acknowledging the processes of creating fiction. This is dramatized by Spufford's discussion of William Holtz' devastating 1993 revelation that the world's cherished assumption that 'Laura the character, Laura the real historical child on the Dakota frontier, and Laura the elderly farmer's wife who wrote the books in the 1930s and 1940s, were one and the same person' was emphatically not accurate. Holtz caused outrage with his declaration that the books had been written not by Laura, but by her right-wing, professional novelist daughter Rose Wilder Lane. Spufford recounts the sense of broken promise implicit in a remark made to him in De Smet by one of the ladies from the Laura Ingalls Wilder Memorial Society: 'I know that if Laura hadn't written those books she'd have said so.' Happily, Spufford's intelligent re-reading of The Long Winter in the light of this information more than compensates for any lingering sense of disappointment at being in some way gulled.

The final chapter descends into the 'hole' of adolescence. There is a brutal sense here that the reading matter of girls and boys parts company for a spell. Having taken the route to literary adulthood prescribed for girls by Spufford with uncanny accuracy (Jane Gardam, Antonia White and Rosamund Lehmann through to Angela Carter and George Eliot, accompanied by a thorough wallow in World War I poetry, which he doesn't mention), I followed his own honest account of a season in porn and science fiction with interest but detachment.

The closing image conjures up the author, desolate, in a bookshop. Into life's narratives the 'drifting pillars' of fictional possibilities will here forever insinuate themselves.