Gretchen Bender

Remember television? Of course you do. In fact, many of us have a set on which we enjoy watching some of our favourite shows, shows whose airing still rakes in considerable ad money, whose actors are still famous and whose production still costs substantial sums. And yet, if you’re a person of a certain age, you must also remember that things used to be quite different for television. Once the bulky centrepiece of every living room, TV used to be the key at-home conduit to the world of moving images. As recently as a couple of decades ago, TV – and the images it aired – was our everything. It was that centrality of the medium that animated ‘Tracking the Thrill’, a strong show (originally curated by Philip Vanderhyden for The Poor Farm, Wisconsin, and now at The Kitchen) of predominantly 1980s-era works from the media artist Gretchen Bender, who died in 2004.

Throughout the 1980s and early ’90s, Bender created several multi-screen media-art installations and also served as an editor, often in collaboration with artist Robert Longo as director, of music videos for bands including Megadeth, R.E.M. and New Order, among others. As a director, her most familiar work is probably the rapid-fire opening credits for the crime-solving TV programme America’s Most Wanted (1988). At The Kitchen, this opener, alongside several other music videos, were displayed on TV sets; despite their original commercial context, they provided the show’s most succinct and enjoyable opportunity to grasp Bender’s broader aesthetic project. In classic examples of the video-clip genre, such as Megadeth’s ‘Peace Sells But Who’s Buying?’ (1986), Bender’s breakneck, potentially epilepsy-inducing editing technique complements Dave Mustaine’s high-strung thrashing. Images of the band on stage playing to a mass of head-banging burnouts are incessantly intercut and overlaid with close-ups of Mustaine’s sneering mouth, licking flames, rapidly pulsating images and logos (a dollar sign, a peace sign, Jesus, and so on) and news images recognizable to anyone who lived through the 1980s: bombed-out refugee camps, Ronald Reagan good-naturedly disregarding reporters’ questions at a press conference, hungry-eyed children in Africa. These only let up midway through, when we suddenly zoom out to an irate father, grabbing the remote control and haranguing his long-haired teenage son, who’s watching the video on TV, ‘What is this garbage? I want to watch the news!’ at which point the boy flips back the channel to Megadeth, scoffing: ‘This is the news!’

This is the news, indeed. The moving image’s prominence and omnipresence, Bender’s work suggests, has nullified once-obvious distinctions between genres and even content. What distinguishes Bender’s style is not only its jackhammer, information-society relentlessness, but also its simultaneity and totality. Everything is happening at once and all the time, and, crucially, in the same space – that of the television screen. This overloaded nowness was present in another video on display, New Order’s rather more cool-to-the-touch but, in its way, no less unrelenting ‘Bizarre Love Triangle’ (1986), which, like ‘Peace Sells’, was edited by Bender and directed by Longo. Alternating rapidly between images of the band and stock-media footage – flowers undergoing an accelerated blooming, commuters marching to work, exploding fireworks and babies’ faces, alongside Longo’s signature freefalling businessmen and some abstracted, pixilated frames – Bender’s editing can be described as almost sculptural, certainly textural. Even though these images create a single cosmology – simultaneously Utopian and apocalyptic – they still palpably chafe against each other as they are reshuffled in line with the music’s inexorable beat.

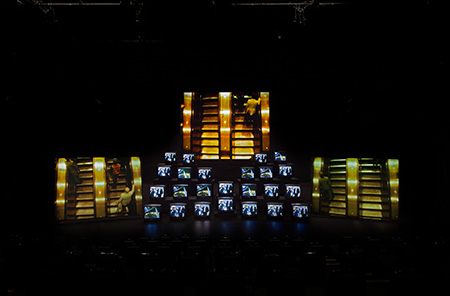

This sculptural quality becomes even more significant in Bender’s multimedia installations. In Wild Dead (1984), 33 monitors showing the same images in unison display abstract, architectural lines and spheres moving through a black vacuum, corporate logos, such as the AT&T globe, stutteringly rewinding and fast-forwarding, the words ‘Video Drome’ spelled out in cocaine-like lines. While the images have a lot to do with the advent of computer graphics, the monolithic, ominous presence in the space is pure TV – and pure sculpture. And despite the three projection screens set up alongside its 24-monitor colossus, the same can be said for Total Recall (1987), an 18-minute video installation that uses plenty of the same unrelenting editing strategies that Bender employed in her more commercial work. An operatically abrasive epic, once again incorporating logos, commercials, slowed down and sped-up fragments from movies (I believe I spotted Oliver Stone’s 1986 film Salvador in the mix), Total Recall in some ways foreshadows – as Bender’s work does more generally – our overcrowded contemporary media landscape. But while the can’t-stop-won’t-stop engagement with images nowadays is concealed by a perceived smoothness, a bandwidth seemingly capacious enough to contain multiplicity comfortably, Bender’s work reminds us of the more aggressive side of this coin. It’s no coincidence that Wild Dead’s soundtrack often sounds like gunshots.