Hannah Villiger

Kunsthalle, Basel, Switzerland

Kunsthalle, Basel, Switzerland

In Samuel Beckett's Happy Days (1961) Winnie sits buried up to her waist in a mound of sand. Her sphere of action is limited to how far she can reach with her arms, and the only way that she can see herself is in a small hand-held mirror. Recognizing only fragments of her body, she still manages to reassemble them into an imaginary whole. The photographs of Hannah Villiger work on a similar premise. A small surface of a white cloth set the stage for the Swiss artist, and a Polaroid camera took the place of the mirror. Villiger took photographs of her body from, at the most, an arm's length away. She stated, 'I am my closest partner and my most obvious subject. With my Polaroid camera I listen to my naked, bare body, the outside of it, the inside of it, traversing it.'

Born in 1951, Villiger trained in sculpture but discovered photography at the end of the 1970s. From 1981 until her death in 1997 she concentrated on taking photographs of herself. She emphatically believed in the power of the body even though, or rather because, she was already coping with the isolation caused by tuberculosis, which she had contracted at the age of 29. She believed not only in a life lived to excess, but also in the idea that photography can somehow renew the physical self.

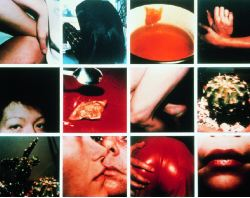

A retrospective of Villiger's photographs is somewhat overdue, given her significance within the realms of body art. This show opened with the single pieces, then groups of works entitled 'Work' from the early 1980s, and led into the 'Sculpturals' from the 1980s and 90s. Villiger arranged single photographs into blocks that defy the logic of the original image. The result is a broken, anagrammatical body, twisted and dislocated by the photographic act. You can imagine this approach as a kind of performance, whose only viewer is the artist herself. The 15 panels of the blocks condense into a kaleidoscopic inquiry into subjectivity and sexual difference. Almost unidentifiable extremities - an embraced neck, a stimulated clitoris - were at the mercy of the artist's camera. Sigmund Freud and Marshall McLuhan described the camera as a type of prosthesis, an extension of the body's organs; it's a viewpoint that becomes abundantly clear in Villiger's work.

In the way they reveal and construct poses these photographs recall the early work of Cindy Sherman or John Coplans. If occasionally Villiger reached for little hand mirrors, like Beckett's Winnie, her intention was not so much to learn to recognize herself better, as to disrupt the act of looking, directing the camera to places where she couldn't reach, the remotest parts of her body, 'the outside of it, the inside of it, traversing it'.

Translated by Helen Slater