Haytham el-Wardany’s ‘The Suspended Step’

A man in Cairo begins to lose his reflection in the writer’s latest short story on selfhood, translated from Arabic by Katharine Halls

A man in Cairo begins to lose his reflection in the writer’s latest short story on selfhood, translated from Arabic by Katharine Halls

I sat in the shade at the tram stop, smoking a cigarette and watching the heavy traffic that clogged the street. The heat was so intense that the tarmac surface in front of the stop had softened, taking on the imprints of thousands of tyres. The waves of noise washing over and around me were becoming more and more intense despite the dead weight of the heat, seeming to rise and fall and fragment into millions of details, millions of tiny specks of sound ricocheting in every direction. The whine of engine belts, the squeal of brakes, the clank of tram carriages, the hacking of exhausts, the blare of horns, the hiss of overheating motors, children screaming and adults yelling, a murmur of conversation from people sitting nearby. The sounds jostled and overlapped and competed and diverged inside my ears while I sat in silence, until I had finished my cigarette and disposed of the stub with a flick of the thumb and index finger that sent it flying into the gutter. Just as I stood up and found my balance, ready to move on, I had a sudden sense that something dangerous and momentous had happened inside me, which then hardened without any obvious cause into the certainty that I was leaving myself behind at this spot for the rest of time, casting my selfhood away and leaving it to disintegrate amid the rising tide of noise that filled the street. I don’t know what happened, exactly, but I knew then that whatever it was, there was no erasing it or going back.

I crossed to the opposite side of Higaz Street then made my way, sweating heavily, down a series of side streets that brought me to the front steps of the building on Sinan Basha Street. There, I put on my suit jacket, fastened my tie, tucked my briefcase under my arm and went up to the second floor. The secretary opened the door for me then returned to her desk next to the doorway, where she was flanked by an electric fan that gave out a loud whine. When I asked for Magdi Bey, she enquired whether it was to do with the switchboard, to which I nodded, and then told me he’d gone out on an urgent errand and had requested, with apologies, that I return in an hour.

‘An hour?’ I asked.

‘An hour,’ she confirmed.

I stopped for a few moments in the blinding sunshine outside the building, wondering what I ought to do next. I realized it was almost rush hour, so I set off aimlessly through the streets of Heliopolis, a neighbourhood I didn’t know well. The streets got narrower and narrower, crowded by buildings and parked cars, and the deeper I went, the heavier the afternoon torpidity that hung over them became, and the hungrier I felt. I was ravenous, actually, and soon my footsteps led me to a place called Piano, the font on its sign designed to look like black and white piano keys set against a background of musical staves. It appeared to be air-conditioned and serving food, so I ducked inside. I went straight to the red-capped cashier, planning to order two slices of margherita pizza, but before I could speak, he informed me that today’s meal deal was a jumbo meat ’n’ mushroom taco sandwich with any soft drink and a slice of Russian cake. When I hesitated for a few seconds, he added encouragingly that it was a great offer, so I decided to give it a try. Then I stood mopping the sweat from my face and neck with a handful of serviettes I’d taken from a stack next to the till and watching the reflections of the diners in the mirrors that lined every wall, until my order was called. I picked up my meal and carried it toward a table so I could eat sitting down, but as I passed one of the mirrored walls, something caught my eye and I turned back, still holding my tray of food, and stood staring until I could see what it was. What had caused me to stop in surprise as I passed the mirror was the fact that my own reflection, glimpsed out of the corner of my eye as I walked, was fainter and less solid than the other reflections. It looked as if someone had taken an image of me and moved the saturation slider down by, say, ten percent. It wasn’t a lot, but it was enough for the difference between my image and all the others to be visible if you paid close attention. I stood observing the reflections of the other people in the restaurant, absorbed in eating their meals and listening to the pop songs coming from the television, and myself standing translucently amongst them: even the taco sandwich and the bottle of cola and the slice of cake on my tray looked sharper than the hands which held them. I stood for a few moments more, gazing uncomprehendingly at the images in the mirror, then continued towards a table so I could eat my meal.

As I chewed at my taco sandwich, I tried to work out when my image could have started to fade. It must have been today, because I’d shaved that morning and hadn’t noticed anything untoward in the mirror. That put it at some point between the time I left the house and the time I entered the restaurant. Then, my thoughts took a darker turn, because it was dawning on me that whatever hand had moved the saturation indicator might continue to do so, which at this rate meant that my image could disappear altogether within a matter of hours. I started to wonder what difficulties this disappearance might pose. For some reason, I glanced around me at that moment, and found I was surrounded by vigorous, youthful men and women, some of them sitting alone staring at their laptops, others in groups huddled around a single laptop. One would make a joke, and the others would burst into laughter, while some listened in silence. Some had round marks on their foreheads from conscientious prayer, and some were wearing headscarves. I tried to relax in the cool air-conditioning, still preoccupied by the thought of my vanishing reflection, when suddenly I found a man standing in front of me, greeting me and asking if he could join me.

‘Sure,’ I said, ‘Go ahead.’

I was trying to work out if he was some distant work colleague, when he asked: ‘Don’t you remember me?’

I scrutinized his face for a feature that might jog my memory, but I had no idea who he was. I asked him to remind me.

‘It’ll come to you,’ he said with a smile, looking me in the eye.

Like me, he was wearing a suit and tie, and carrying a leather briefcase, though his clothes were more elegant than mine.

‘I hope I’m not keeping you from anything?’ he asked.

‘Oh no, nothing important,’ I replied.

He settled into the chair opposite and asked, still smiling: ‘How are things with you?’

‘Not bad, thanks.’

‘You look pensive.’

‘Pensive? Or pale?’

‘Pale? Not at all. Your face is full of life. But I must say, you do look … I’m not sure how to describe it. Like someone from somewhere else. Like someone who’s ended up in the wrong place.’

‘Really?’ I exclaimed.

‘But why do you think you look pale?’

‘No, no reason.’

My interlocutor fell silent for a few moments and looked around him. The television blared, mingling with the voices of the people nearby.

‘Do you know who this singer is?’ asked the man finally, changing the subject.

I listened for a while to the music blasting from the television, then shook my head.

‘I can never tell these young pop singers apart,’ he said.

‘I only know the names of the old ones, myself,’ I agreed.

‘Do you mind if I ask what you’re listening to these days?’

I was taken aback by this question, which implied an awareness of my personal interest in music.

‘I don’t listen to anything in particular,’ I replied. ‘I just put the radio on now and then.’

My interlocutor smiled broadly, and when he did that, a familiar twinkle lit up his eye.

‘No way!’ I cried. ‘Giddo!’

It was my high-school friend Abdelmagid. How on earth had I forgotten his face? I looked at him searchingly, and bit by bit, I began to discern the effects of the intervening years: his jowls were heavier, his right eye bulged a little; there was a new mole on the tip of his nose, and most of his hair was gone. For the second time today, the transformations of a face gave me pause; Giddo’s face as I was seeing it now, having finally recognized him, was an ever-so-slightly edited version of Giddo’s face as I had known it in the past. It was like looking at one image and instead seeing another very similar image that was nevertheless not the same one at all.

‘Such a weird coincidence, isn’t it?’ said Giddo. ‘What are you doing in Heliopolis, anyway?’

‘Just some work,’ I replied. ‘You?’

Giddo told me he was now a partner in a contractor’s firm based on Farid Sameika Street, which was close by. He had spent many years in Kuwait after finishing his civil engineering degree, he said, only returning last year.

‘How about you?’ he asked, looking at me. ‘What do you do now?’

‘Still a sales rep,’ I said.

I recalled the familiar cadence of Giddo’s voice. He articulated his letters clearly and gave each word its weight within the sum total of what he was saying, so that the words came out not rushed and elided but discrete and unambiguous and unhesitating. When he fell silent now, however, his words mingled with those of others, and the fall of his voice on my ears reverberated amid a chorus of murky sounds from long ago that drifted past like a cloud of indeterminate form, carrying the voices of classmates and teachers, the ‘Triumphal March’ from Aida, the flag salute.

Giddo turned his head and cast his gaze around the room. ‘It’s such an amazing coincidence,’ he said in disbelief. ‘Such an amazing coincidence.’

We went outside and smoked two cigarettes, then Giddo insisted we have a cappuccino, his treat. The restaurant wasn’t so busy now, and we sat at our table sipping our coffees.

‘What about you?’ I asked. ‘What are you listening to these days?’

He dismissed the idea with a wave. ‘My music collection got wiped out over the years,’ he replied. ‘All I have left is a few tapes I listen to now and then in the car, and apart from that I don’t listen to anything. Work just gets busier and busier.’

I nodded in affirmation. We sat silently for a few moments, then Giddo said: ‘You know, it really is an amazing coincidence we bumped into each other. Not because this is such an unlikely place, or because it’s been such a long time, but because I’ve been feeling funny all day. Since I left the house this morning, I’ve been feeling like I’m living through some other day, a day out of the past, and now suddenly I meet you. That’s what makes it such an amazing coincidence.’

‘I’ve also had the feeling there’s something odd about today. I sat down at a tram stop so I could smoke a cigarette in the shade before my work appointment, and then when I got up, I suddenly had this feeling that something inside me had changed forever, that I’d left my old self on the seat at the tram stop.’

‘Weird. And what’s your new self like?’

‘The strange thing is I don’t feel like I’ve got a new self. I just knew I was losing the old one.’

Giddo proposed that what was really behind my feeling of having left my old self behind was some desire to change my life, and that I should think about introducing some new element into my existence – a new job or new hobby, or maybe a new love interest. He instructed me seriously to plot out in my mind the path my life had taken so far, and then ask myself a question: do I want to follow this path to the end? Or might I want to follow a different path from here on?

Giddo glanced at his watch and said he had to make a move so he could pick up his daughter from nursery, offering to drop me off somewhere on the way; I thanked him and said I needed to go back and see the client I’d missed earlier on. Then he took out his wallet and pulled out a business card which he handed to me, urging me to stay in touch.

I smiled back, gazing at the card. ‘Yes, definitely,’ I replied.

Giddo gave me a hug, then picked up his briefcase and set off.

My hour was up, and it was time to go back and meet Magdi Bey. As I sat, I thought about what a coincidence it was that I’d bumped into Giddo, then remembered my disappearing reflection; my anxieties returned, and I got up quickly to leave, resolving to take a good look in the mirror as I passed, so as to check how much more my image had faded. I put on my jacket and picked up my briefcase; I was holding Giddo’s business card in my hand all the while, and I looked briefly at it once again, then put it down on the table and left.

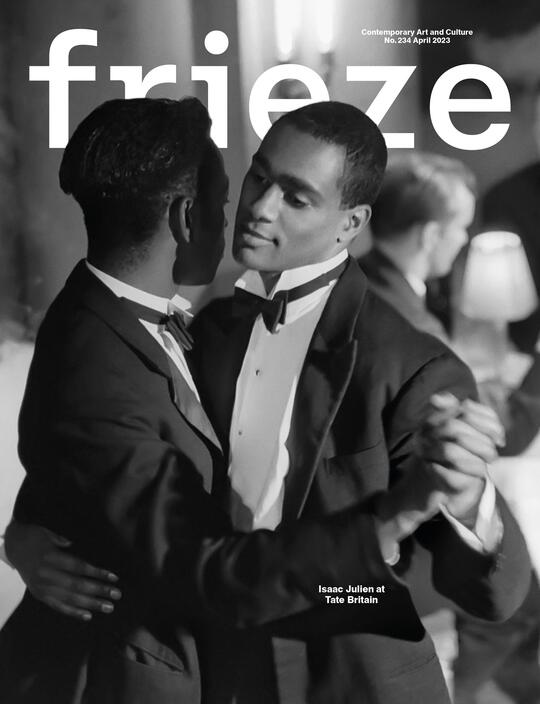

Main image: illustration by Lucas Burtin, 2023