Hello, Sam

Brian O'Doherty's homage to Samuel Beckett

Brian O'Doherty's homage to Samuel Beckett

Arts are positional games and each time an artist is influenced he rewrites his art’s history a little.

Michael Baxandall, 1985

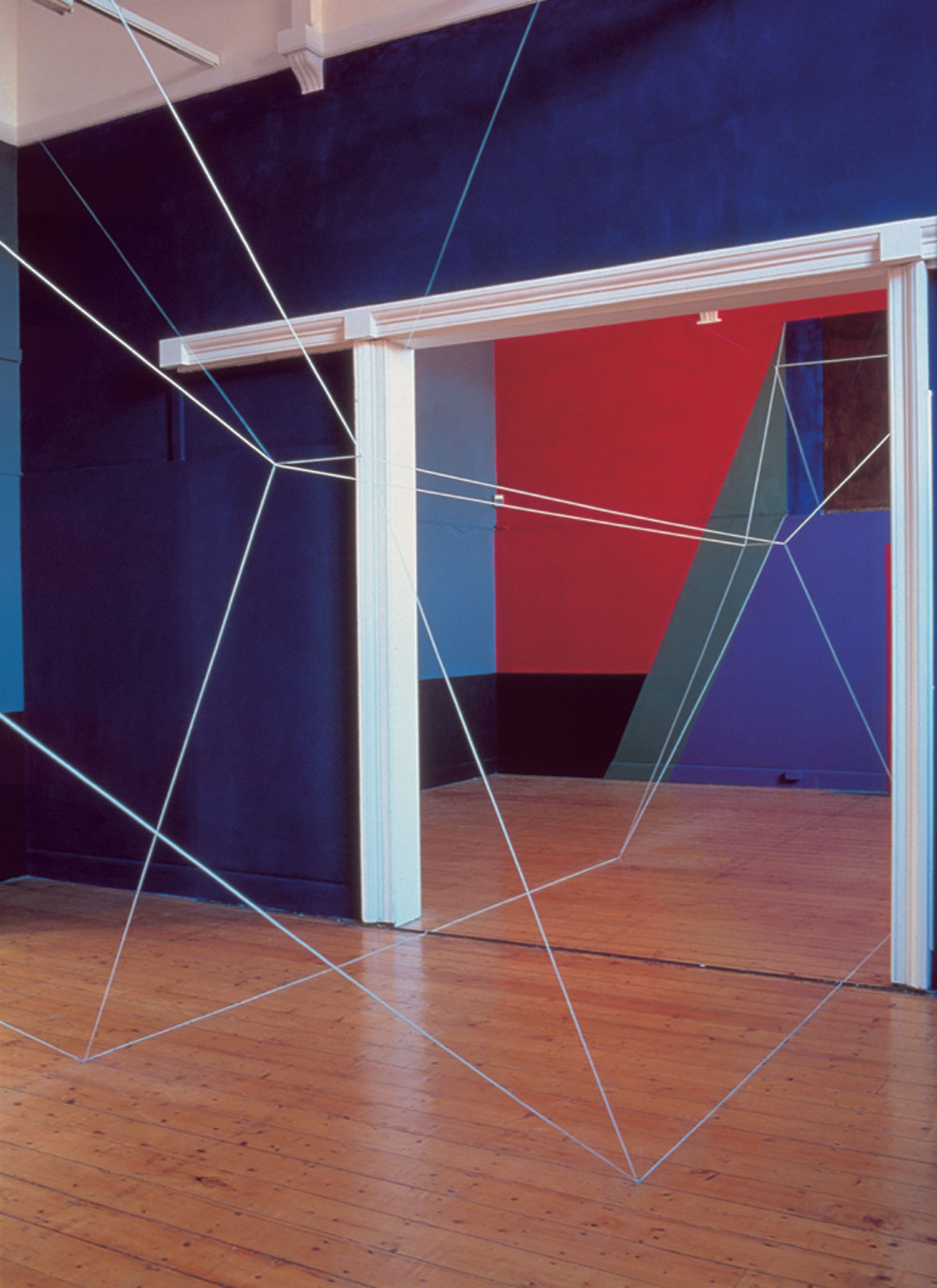

The recent collaboration between the theatre group Gare St. Lazare Ireland and artist and writer Brian O’Doherty provided a rare combination of theatre, song and visual art. It took place at the ‘Beckett in London Festival’ from 21 May – 5 June at the Print Room, Coronet Theatre in London’s Notting Hill in celebration of the playwright’s 110th birthday. Gare St. Lazare Ireland, Paul Clark and Caoimhín Ó Raghallaigh’s performance Here All Night is based on texts, songs and music from Samuel Beckett’s work; it was first performed at the Brighton Festival in 2013, and then at the Lincoln Center, New York, in 2015. O’Doherty’s Hello, Sam Redux, Rope Drawing #126 (2016) was incorporated into Gare St Lazare’s performance for the first time. This was also the first exhibition of O’Doherty’s art in England in 40 years.

Hello, Sam Redux comprised a centrally suspended, bog-like body in a ‘no-space’ at the centre of a dimly lit stage. Further rope lines stretched to the ceiling above. This stark space recalled the inside/outside tension of Beckett’s texts, the mysteriousness of his cosmos and his insistent ghostly presence. Actor Conor Lovett and singer Melanie Pappenheim, accompanied by a chorus embedded within the audience, and an onstage musical trio, circulated around and within the ‘no-space’ of the effigial presence lit by a single light-bulb from above. At the periphery, three stations marked by a chair and headphones invited the audience to listen in. One side of a ‘conversation’ could be heard at each station. The texts were created and spoken by Eoin O’Brien, doctor and author of The Beckett Country (1986) and Michael Colgan, Director of Dublin’s Gate Theatre, which has performed all of Beckett’s plays. Beckett’s Text for Nothing #8 (1958) could be heard at the third station, recorded by Jack MacGowran in 1967. All three performers knew Beckett in his lifetime (the playwright died in 1989).

O’Doherty is also a medical doctor, a novelist (for which he has been shortlisted for the Booker Prize) and an art critic (most famously for Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space, 1976). Reflecting on the central conceit that he had ‘miraculously resurrected’ Beckett, his installation recalls the ‘conversations’ that artists often have with others from different generations or disciplines: Pablo Picasso and Paul Cèzanne, Beckett and Marcel Proust, or O’Doherty’s own ‘conversation’ in his Portrait of Marcel Duchamp (1966-67). This ‘animated’ electrocardiographic tracing of the older artist’s heart not only challenged Duchamp’s dictum that art died on the museum wall, but also paid homage to his pervasive influence by slowing the beat to extend it by 200 years beyond his death, the year after O’Doherty’s conceptual portrait. Over a 50-year career O’Doherty and his most renowned alter ego, Patrick Ireland (1972-2008), have engaged in many such ‘conversations’. Via his ‘Rope Drawing’ installations, O’Doherty/Ireland has had dialogues with the 17th-century Italian architect Francesco Borromini and the Russian Suprematist artist Vladimir Tatlin.

But O’Doherty’s range of interests also includes an approach that ‘speaks’ to literature. After he emigrated to the United States from Ireland in 1957, his work often referred to the weighty literary legacy of Irish writers. Thus, within the context of the conceptual period, of which O’Doherty is a pioneer, In the Wake Of...(1963/4) – and Patrick Ireland’s later Rope Drawing # 73, The Purgatory of Humphrey, Chimpden Earwicker, Humunculus in 1985 – challenged the legacy of James Joyce from within the visual arts. But what of Beckett?

In the ‘conversation’ that I imagine O’Doherty and Beckett might have had in the context of Hello, Sam Redux, I feel sure that they would have reminisced about O’Doherty’s phone-call from New York to Paris in 1967, when he invited Beckett to submit something to his ‘conceptual’ edition of the avant-garde box/magazine, Aspen 5/6. They would have discussed the central themes of Aspen 5/6: time (in art and history), silence and reduction, and language, common interests to both artists. But the conversation might also have included the nature of the self, given that the first publication of Roland Barthes’ famous essay ‘The Death of the Author’ was commissioned by O’Doherty for Aspen 5/6. A common distrust of language by both artists might have also led to a discussion about the structural affinities between Beckett’s late television play, Quad (1981) and O’Doherty’s earlier Structural Plays (1967-1970) that utilized the archaic Celtic language of Ogham in a performative way. (Structural Play #3 was also included in Aspen 5/6.) Beckett agreed to O’Doherty’s request by providing Text for Nothing #8, with the proviso that it be recorded by MacGowran.

The affinities shared by O’Doherty and Beckett also extended to opposition to the single unified self. These are borne out by the several personae O’Doherty adopted in his work (including Sigmund Bode, Patrick Ireland, Mary Josephson and William Maginn) and Beckett’s observations in Text for Nothing #8: ‘All I say is false and to begin with not said by me...but that other who is me, blind, deaf and mute … in this black silence.’

Finally, in this imagined conversation between such significant figures, O’Doherty may have mentioned how surprised he was to learn of Beckett’s intense interest in psychology and psychoanalysis and their contribution to an understanding of the mind/body problem. The knowledge accrued from his ‘Psychology Notes’ (1934/1935) – first revealed in James Knowlson’s biography Damned to Fame (1996) – to his reading, like O’Doherty, of William Osler’s popular textbook The Principles and Practice of Medicine (1901), as well his friendship with James Joyce who had begun the study of medicine on three occasions, all crept into his work. O’Doherty’s thinking also reveals his medical knowledge and the fact that he had studied at the Experimental Psychology Laboratories in Cambridge University, England, in the mid-1950s. It is little wonder, then, that – although of different generations – (O’Doherty was born in 1928) both artists explore the fragility of self, language and the nature of reality and representation.

Although Beckett has now left us, his work lives on through the work of such inspired groups as Gare St. Lazare Ireland. It also lives on through O’Doherty’s artistic engagement in Hello, Sam Redux, which so powerfully renders Beckett present with minimal visual and auditory means. O’Doherty, thankfully, is still with us and constantly active through his art, novels and non-fiction writing. His third novel, The Crossdresser’s Secret was published in 2014. His latest Rope Drawing, Parallax City # 125 (2016) can be seen until September 5 in the exhibition ‘Dis-play/Re-Play’ New York’s Austrian Cultural Forum and Standing Magic Square Redux Rope Drawing #19 (1976) (#127, 2016) will be recreated for the 40th anniversary of PS.1 in New York (19 June – 29 August). According to Gare St. Lazare’s website, it may be possible for new audiences to see this superb joint production later this year in Boston. It should not be missed.

Lead image: Here/Now, Rope Drawing #122, 2014. Courtesy: Simone Subal, New York