Highlights 2013 - Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie is a writer based between Beirut, Lebanon and New York, USA.

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie is a writer based between Beirut, Lebanon and New York, USA.

I won’t lie to you, 2013 has been hard, and I’m glad to see it end. For whatever reason, it seems as though I’ve spent the past 12 months tugging on two strands of experience – one with art, one with books – trying to braid them around a cruel and unruly cord of current events. At the time of this writing, I’m seven hours behind and nine thousand kilometres away from a city I’ve made my own, Beirut, where another massive car-bomb blast has killed another mid-level politician, but this time in the dead centre of the downtown district, at the height of the morning commute, killing seven, wounding a hundred, and breaking all manner of unspoken rules in the war without end that goes on, undeclared, for years, decades, centuries, what feels like forever. Worn down by proximity to the Syrian civil war, among other things, and willfully dislocated to New York, I’m now distractedly clicking through images on my computer of charred cars, bodies, and buildings. There, running through the centre of one particular picture, is the low-slung wall behind the Starco Center, where, just seven months ago and a world away, the writer and critic Ghalya Saadawi gathered a group of us for a walking tour, titled After the Future: Heritage Redux, which she led several times, mostly at night, during the sixth edition of the Home Works Forum on Cultural Practices, organized by Ashkal Alwan in May.

Saadawi’s tour – with its playful appeals to time travel, storytelling, and blistering political critique, alongside its powerful evocations of anger, melancholy, and imaginative escape – had shaken me deeply. Her work had revived urgent questions about the loss of the city that had all but disappeared from the discourse in Beirut, where it had been said and assumed, for years, that in terms of public space, we had lost, period. And would keep on losing, over and over again, whether to war or political dysfunction or rapacious real-estate development or a disturbingly uneven economy, what difference did it really make. And so I had been writing about this, back and forth, to Saadawi, that occasion for debate and further discussion being the great pleasure, challenge, and solace of this line of work. On the day of the explosion, she wrote: ‘This bomb went off just on the site where we met on those spring nights. It’s eerie. What do we do with all this accumulation?’ Seriously, what do we do? And for how long? And will it ever make any difference? And does it not seem, sometimes, like the saddest thing in the world that we think art – of all things – will not only hold that accumulation together but allow us to sort through and make sense of it all?

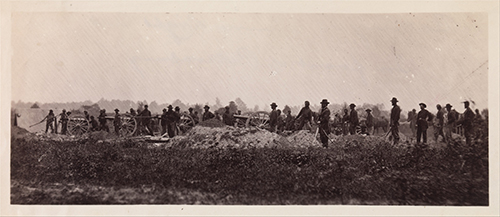

The past year of looking at art, whether to avoid or to answer or to think through those questions, was bookended, suitably enough, by two remarkably strong exhibitions exploring the role of photography in times of war. ‘Photography and the American Civil War’, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, was meticulous, erudite, and precise, an education that hummed through at least six different levels of learning (photography as business, journalism, propaganda, history, memorial, fable, and more). ‘WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath’, at the Brooklyn Museum, was (and through February 2, still is) messy, cluttered, all over the place in too small a space, and intense enough to break your heart (see Tim Hetherington’s video diary) and make you think and send a deep, unsettling wave of nausea through the core of your being. It is also refreshingly international and does not shy away from the complexities of debate, doubt, and anguish that are inevitably raised by a number of iconic images, from Roger Fenton’s cannonballs and Robert Capa’s Fallen Soldier to Spencer Platt’s picture of four young women and one young man, all packed into a Mini Cooper, taking pictures with their mobile phones of the wreckage that surrounds them in the southern suburbs of Beirut after of the war with Israel in 2006. War tourists, callous members of the haut bourgeoisie, concerned citizens, distraught areas residents, indignant activists? The samidoun sticker on the dashboard (Arabic for ‘steadfast’) is something that until this exhibition I’d never noticed before, and I’ve looked at that image a hundred times.

In between those shows, the revolution that began three years ago in Egypt frayed and fell apart, Turkey erupted in euphoric protests but events there have since taken many worrying turns, leftist politicians were picked off one by one in Tunisia, Syria descended into total, unconscionable chaos, Lebanon became totally hopeless, and a civil war in all but name continued to burn through Iraq, a twisted model for the rest of the region. Then, in the space of a single day in Istanbul in September, two very different works in two very different venues (a piece by Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster at collectorspace and a terrific installation by Ruanne Abou-Rahme and Basel Abbas for the Istanbul Biennial) brought me back, curiously, to the heart of Roberto Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives (1998). In that novel, we fall in love with both the figures and the friendship of Arturo Belano and Ulises Lima, poets of the visceral realist school, orphans of an absent avant-garde, who are searching for the lost works of their chosen forebear, Cesárea Tinajero. When they find her poems, they turn out, much to their confusion, bewilderment, and wonder, to be pedagogical drawings: a straight, a wavy line, and a jagged line. They mean nothing, and everything, and in one way or another, they represent the movement of our lives, and the intensities of our experience. With that in mind, the art works that made the greatest impression on me this year were the ones, at it were, that most dramatically bent my line.

John Akomfrah’s The Unfinished Conversation (2012) shown at the 11th Sharjah Biennial traced the history of race, identity, political thought, and cultural production in the late twentieth century through a gorgeous, three-screen video installation on the life and work of Stuart Hall.

Rabih Mroué’s Riding on a Cloud (2013) for Home Works 6, possibly the artist’s best and most emotionally gutting performance to date, delved into the specific story of his brother, Yasser, who was shot in the head shot by a sniper on the day their grandfather was assassinated, and the more general condition of leftist intellectuals and progressive political thinkers being purposefully killed, depriving a country, a society, and a culture of the lungs needed to breathe in new ideas and much needed reforms.

Édouard Manet’s L’Evasion de Rochefort at the Palazzo Ducale was the thing that shocked and haunted my run through the 55th Venice Biennale, and also the thing that struck me as most beautiful and painful of all. Done in the last years of Manet’s life, it is a history painting – depicting a dissident journalist’s dramatic escape from impending incarceration – that consists almost entirely of a churning, blustering sea. Off center, white-capped waves rock through a tiny lifeboat, which is either being pursued or saved by a dark shadow falling across the horizon.

Jean-Luc Moulène’s Debrayeur anchored a stunning solo show at the Beirut Art Center. Two L-beams – one red, one blue – wrapped around the main exhibition hall and bifurcated the space. Produced in Beirut and commissioned for the exhibition, the steel structures, when viewed from above, formed two rectangles bolted on top of one another but shifted slightly apart. The title, French for ‘disengage’ but also the word for a clutch pedal, was a perfect metaphor for Moulène’s unrivaled practice, as a mechanism controlling how two entities moving at potentially different speeds connect and decouple, if and when needed.

Ruanne Abou-Rahme and Basel Abbas’s The Incidental Insurgents: The Part About the Bandits (2012-13), for the 13th Istanbul Biennial, grafted Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives and the writings of Victor Serge (including Memoirs of a Revolutionary) onto the question and condition of Palestine. Staged like an abandoned studio, the installation pulled viewers into a rich, layered world of associations and clues, making us all amateur sleuths in the search for meaning (and the desire for political change).

Jumana Manna’s For Those Who Like the Smell of Burning Tires at the CRG project space in New York made a spry, subtle, sophisticated statement about masculinity and nationalism with three bent flagpoles, each eight meters tall and totally deformed.

Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch paired with Carel Fabritius’s The Goldfinch at the Frick might have been cleverly cross-promotional but who cares. Tartt’s third novel not only blends the driving, plot-twisting storytelling of Dickens and Tolstoy, it is also a riveting example of ekphrasis in fiction. Moreover, the final chapter reveals itself as the end of long letter, furiously written, desperate, agitated, guts on the table, going for broke to explain how and why an object of art, so dumb and inert by itself, could possibly mean so much to us. I finished the book and I cried for days. I went to see the painting and I was moved, strangely, not so much by how much had been illuminated by the novel but by how differently I saw the work myself. All of Tartt’s conclusions were there – beauty leads to ruin, we are possessed of a heart we cannot trust, life is a disaster, art works speak across time and hold a history of love and ‘the people who have loved beautiful things, and looked out for them, and pulled them from the fire, and sought them when they were lost’. But there’s something else, too. As Arturo Belano and Ulises Lima say after puzzling over Cesárea Tinajero’s poem: ‘It’s a joke, Amadeo. The poem is a joke covering up something more serious.’