Highlights 2014 – Sam Thorne

Last spring I moved from London, where I'd been living for seven years, to St Ives. A mere 5½-hour train journey from the capital (or, if you're intrepid, a night on the sleeper train), the small Cornish town is perched close to Britain's southwestern tip. It's been a home to artists and writers since at least the 1880s. As the artist Linder – the inaugural resident artist at Tate St Ives, where I work – pointed out to me soon after I arrived in March, it's a place where the ghosts of modernism are everywhere palpable. It's also a place where, thanks to the legacy of artist-potters Bernard Leach and Shoji Hamada, the veil between art and craft feels especially thin.

Last spring I moved from London, where I'd been living for seven years, to St Ives. A mere 5½-hour train journey from the capital (or, if you're intrepid, a night on the sleeper train), the small Cornish town is perched close to Britain's southwestern tip. It's been a home to artists and writers since at least the 1880s. As the artist Linder – the inaugural resident artist at Tate St Ives, where I work – pointed out to me soon after I arrived in March, it's a place where the ghosts of modernism are everywhere palpable. It's also a place where, thanks to the legacy of artist-potters Bernard Leach and Shoji Hamada, the veil between art and craft feels especially thin.

How all this inflected what seemed most important to me in 2014, I’m still not sure. On some level, though, this has been a year where I’ve had to give a lot of thought to the relationships and frictions between location and production, between the myths of modernism and who gets to tell them, about all those industries circling around what Lucy Lippard called the ‘lure of the local’. Certainly my new location, at a remove from a major city or airport, has meant I’ve travelled less regularly than before. While that didn’t result in anything close to the extra time to read or write I’d imagined, it did mean fewer distractions, the occasional possibility of pursuing half-formed ideas for longer than I was accustomed to. I’ve read less, but less frantically, and I’ve looked in the same way; both have often been sporadic, squeezed between the demands and confusions of any new position or place. So here are some of my highlights, in fragments.

Looking

What to say about ‘Carl Andre: Sculpture as Place, 1958–2010’ at Dia:Beacon? It’s unusual for an exhibition to completely overhaul your opinion of an artist; extremely rare for it to revise your thinking of a whole period – in this case the 1960s and ’70s, the claims and legacies of minimalism, as well as so much more. I spent a long afternoon there during a New York trip in June, though a few weeks too early to catch the Jeff Koons extravaganza, the Whitney’s Breuer building swansong. From afar, though, it was dispiriting to see how few substantive critical responses it generated. Whatever the publication or platform, most critics seemed happy to settle for with one of two responses: a sign-o’-the-times shrug, and ‘Is this guy for real?’ Maybe I’ll get a chance to see it at the Pompidou. I did see Koons elsewhere though: ‘Sculpture After Sculpture’ at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm put him alongside Charles Ray and Katharina Fritsch – all three were born within a few years of each other in the mid-’50s – in a forensically installed one-room inquisition into post-pop figuration. Chilling and exhilarating. Kudos to Jack Bankowsky for pulling it off, and to Daniel Birnbaum for overseeing a programme that in the last couple of years has accommodated both Hilma af Klint and the much-missed Sturtevant, who died in May.

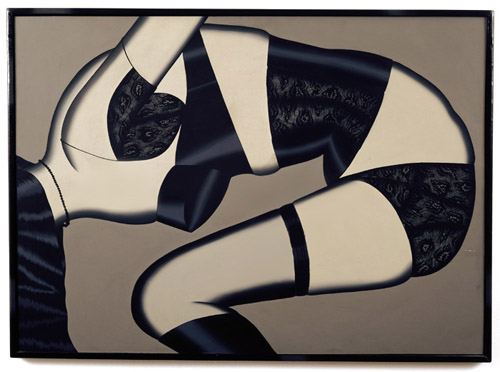

More often I found myself thinking more about the modest-scaled, private or homespun, whether that was Lucy Rie’s pots (winningly paired with photos by George Platt Lynes at Kendall Koppe in Glasgow), 40 years’ worth of never-before-shown works by Lukas Duwenhögger at Rodeo’s new London gallery, dozens of Lynda Benglis’s convulsive ceramics at Thomas Dane, or ‘Unwoven World’ at OCA in Oslo, tough and tender 1970s textile works by three Norwegian artists. Two shows I couldn’t stop thinking about both involved collage: Vincent Fecteau at Matthew Marks in New York and the Whitechapel’s revelatory Hannah Höch survey at the Whitechapel. Also, such a pleasure to see the work of the slightly forgotten Chicago Imagist Christina Ramberg on two occasions, first at Glasgow International in April then at the Liverpool Biennial in September. Speaking of GI, Sarah McCrory’s inaugural edition felt fresh: a minor coup with a wittily installed Jordan Wolfson retrospective of sorts, a funny-heartbreaking performance by Sue Tomkins, collages by the late – and, in the UK, little know – Brazilian artist Hudinilson Jr, cavorting SketchUp’d tableaux by the young New Yorker Avery Singer, and a lot more besides.

What else sticks with me? It’s a jumble, but PS1’s bracing Maria Lassnig retrospective – which opened just a couple of months before the Austrian painter died aged 94 – won’t be easy to forget. (I wonder what she’d have thought of ‘The Forever Now’, which just opened at MoMA?) Back in London, the same goes – though in ways that couldn’t be more different – for Pierre Huyghe at Hauser & Wirth and Yvonne Rainer at Raven Row. In Barcelona, MACBA’s retrospective of Oskar Hansen had a lot to say about dreams and influence, including work by the visionary Polish architect’s students alongside his own ‘Open Forms’. In August I spent a sweltering couple of weeks travelling from Istanbul to Armenia via Georgia, where I saw for the first time the remarkable paintings of Niko Pirosmani, the early-20th-century self-taught sign painter. Though he died penniless, he had in the 1910s shown in Moscow alongside Kazimir Malevich, whose first-ever UK retrospective, at Tate Modern, was from start to finish unforgettable. And, before I forget, the Serpentine had a number of strong shows, from Martino Gamper’s collections of other peoples’ collections in the spring and Ed Atkins’s Purcell-singing avatar Dave in the summer, to Trisha Donnelly in the autumn – evasion and spareness, sure, but also beauty.

Listening

I found myself consuming more music than every before, and – oddly? I’m not sure – this was usually in the old-fashioned long-format kind of way: albums, mixes, stacks of reissues. In the latter camp, my go-to accompaniments to long train journeys were compilations of ambient and synth music. Half of Craig Leon’s Anthology of Interplanetary Folk Music Vol. 1 was put out by John Fahey in 1980, following the studio whiz’s pioneering work on a ridiculous number of debut LPs: Suicide, Blondie, the Ramones etc… The music collected here was inspired by and named for a 1973 exhibition, at the Brooklyn Museum, of sculptures by the Dogon, the Malian tribe whose beliefs are based on a visit by extraterrestrials named Nommos. It found a counterpart in the 30-year rerelease of Structures from Silence by Steve Roach, a classic of ambient music. Both albums sent me back to Brian Eno, of course, as well as the (Cornwall-born) Aphex Twin. In terms of mixes, I got lazy, relying on pretty much one source: FACT magazine. My favourites of their weekly installments came c/o Forest Swords, P. Morris, Murlo and Claude Speeed. Other things I returned to over and again came from Nguzunguzu, Soda Plains and Celestial Trax. With all of these, the lines between mixes ‘proper’ albums felt nebulous, but – for balance – some actual LPs I returned to: Dean Blunt, Popcaan and Tinashe, alongside older things by Alice Coltrane and Francis Bebey. Special mentions, too, for $3.33’s Steve Reich-channelling Draft and Mamman Sani’s Taaritt. Recorded in the late 1980s in Niger and Paris, the latter comprises future-facing synth re-imaginings of ancient Saharan ballads – like a forgotten soundtrack to David Lynch’s Dune.

And Looking Forward

What to look forward to? It’s already been well articulated by so many respondents to this survey, but 2014 will inevitably and rightly be remembered as a year of disappointment and catastrophe. This year – whether in search of solace, of ways out or forward – I plan to do a lot of reading. On my shelf are books old and new by Ben Lerner, Saskia Sassen, Mathias Enard, Ursula Le Guin, Naguib Mahfouz, Alexander Kluge, Achille Mbembe and Caroline Jones. Exhibitions? This week I’m catching the tail-end of Mark Leckey’s retrospective at Wiels in Brussels, a godfather of a kind to a number of the artists included in the 3rd New Museum Triennial, which opens next month. And then of course I’m more than intrigued by what Okwui Enwezor will do with Venice. The last large-scale exhibition of his I saw, the 2012 Paris Triennale, was concerned with the spectre of the colonial-era ethnographer. Grand, lofty, flawed – it also felt like unfinished business. In the autumn, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev will ‘draft’ (rather than curate) the 14th Istanbul Biennial, with some intriguing allies: Pierre Huyghe, Griselda Pollock, Füsun Onur and Anna Boghiguian, among others. After the capitulations of the last edition, not to mention the myriad lessons of Documenta, I am excited to see what she can achieve.

Wherever you’re calling from, here’s to a happier 2015.