A Highway to India?

Market interest in Indian contemporary art has had some unexpected benefits for the subcontinent

Market interest in Indian contemporary art has had some unexpected benefits for the subcontinent

There’s nothing particularly unusual about spying Julian Opie’s faceless pole-dancers at art fairs or on postcards in museum shops in London and New York. But, until January, which saw Opie’s first solo show at Sakshi Gallery in Mumbai, you wouldn’t have encountered them in India. A few months before that, Sotheby’s hosted a preview of Damien Hirst’s ‘Beautiful Inside My Head Forever’ in Delhi before work from the exhibition was auctioned in London in September last year. India has been on the agenda for other international artists too. New Yorker Jon Kessler paid a visit to Mumbai in October 2008 and gave a lecture on his work at Bodhi Art Gallery, while Marc Quinn accompanied curators from the Serpentine on a trip prior to the gallery’s recent ‘Indian Highway’ survey.

A cynic may chalk these increasingly frequent visits up to mercenary tactics – perhaps Sotheby’s was merely keen to off-load Hirst’s familiar staples onto untried audiences? Maybe, though such suspicions shouldn’t detract from the various benefits that India’s sudden appeal has created. In the last two years, commercial galleries have radically broadened their programmes: Gallery Maskara in Mumbai, for example, was founded last year by Abhay Maskara to provide a platform for ‘radical and excellent art, which goes beyond the nationality of the artist’. Belgian sculptor Peter Buggenhout’s solo show, ‘Res Derelictae II’ (July 2008), marked Maskara’s third exhibition and the gallery’s most challenging display yet. Likewise, Mumbai’s Galerie Mirchandani + Steinruecke has hosted several diverse exhibitions, from Kiki Smith’s fairytale-inspired prints (December 2007), to a performance by Jonathan Meese (January 2008) – which involved the German artist running around for more than an hour yelling about ‘the dictatorship of art’ to a bewildered audience (some of whom beat a hasty retreat) – and comparatively tame paintings by Berlin-based Norbert Bisky (December 2008). More recently, Sakshi Gallery launched a group show of African artists, ‘Chance Encounters’ (until May), that included three of Ghanaian El Anatsui’s gorgeous gold-flecked installations: aluminum bottle-caps and copper wire simulated swathes of hand-woven fabric.

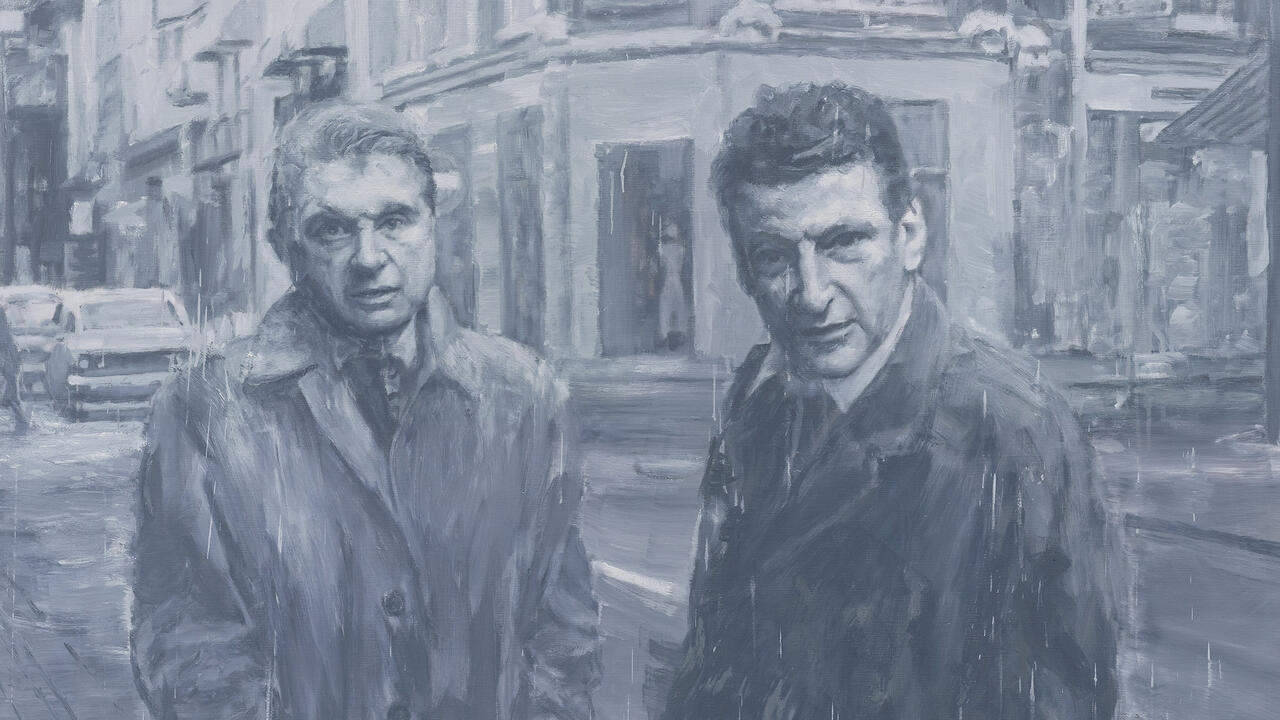

Jonathan Meese at Galerie Mirchandani + Steinruecke, Mumbai. Photo: Jan Bauer. Courtesy Contemporary Fine Arts

There may be good reason to fear that this steady trickle to India will dry up with the recession. Early in 2009, the market-savvy Bodhi Art shut down its branches in Delhi, Singapore, New York and Berlin. (It now only retains its presence in Mumbai.) Given that BodhiBerlin was founded in May 2008 with the express purposes of helping Indian artists to reach a new audience and European ones to launch themselves in India, its closure is bound to loosen India’s precarious foothold in the global art market. Moreover, Bodhi pulled the plug on a Julian Schnabel exhibition slated for December 2008. ‘The artist felt, as we did, that it was not the right time to have the show,’ says Sharmistha Ray, Director of Bodhi Art. Adding that, ‘We’ve always thought globally and that hasn’t changed.’ If Ray remains optimistic, Maskara is unfazed: ‘The boom did not dictate my programme and the bust certainly will not.’ He has, nonetheless, suffered a rude shock recently. After being invited in early 2008 to show in ARCO Madrid 2009’s India-themed exhibitions, his gallery was dropped from the main section of the fair in November, ‘due to various reasons including […] our largely international programme.’ Maskara says he was then offered a chance to put his ‘Indian artists’ in the curated section, but ‘flatly refused’ to.

Which begs the question: what makes an artist international? Is it based on where they exhibit or the quality of their art? Inconclusive surveys – such as the over-stuffed ‘Indian Highway’ (now showing at the Astrup Fearnley in Oslo) – leave the issue of visibility and origins open to debate.

Subodh Gupta, Line of Control (2008)

It’s intriguing that the largest work in Nicolas Bourriaud’s studiedly multinational Tate Triennial, an exhibition originally founded to provide a platform for new British art, was Delhi-based Subodh Gupta’s gigantic mushroom cloud of shining steel utensils. Such acknowledgment presents a catch-22 situation for artists like Gupta: if there was pressure on him to perform national stereotypes to build up recognition in global circles, there is just as much pressure not to be confined by them now. Two years ago, Gupta was applauded by the world’s press for his use of materials of supposedly ‘ethnic’ significance – stainless steel, cow dung and brass. Lately, he has been chastised for an excessive use of these indicators. Where does the line between ‘Indian enough’ and ‘international’ lie?

Subodh Gupta, Date by Date (2008), at ‘Indian Highway’ (2008-9)

While ‘international’ is often bestowed on artists who regularly exhibit away from their home turf, it is a frustratingly paradoxical term given that it’s tempting to conclude that such success is often achieved by emphasizing origins. (Gupta isn’t the only artist who has made it abroad, by playing up his ‘Indian-ness’; now represented by Haunch of Venison, Mumbai-based Jitish Kallat’s 2008 solo show in Zurich was flooded with India-specific reference points.) Yet there have been exceptions to the rule. No one could claim that the austere line drawings and ‘abstract’ photographs of the late Nasreen Mohamedi are overtly Indian. Practicing abstraction in 1980s’ Baroda – when everyone else seemed to be exploring ‘narrative figuration’ – the artist’s monochromatic musings are now collected by a number of museums around the world. (The Office for Contemporary Art Norway in Oslo is holding a tiny retrospective of her work, ‘Reflections on Indian Modernism’, from May til June this year.)

Nasreen Mohamedi, Untitled (undated). Courtesy of the Glenbarra Art Museum Collection, Japan

So what is to be expected from western stars showing in India? Is a good exhibition equally strong wherever it takes place? Kessler doesn’t think so: ‘Mumbai is itself like a huge installation and any artist who exhibited there would have to make work accordingly.’ Certainly, Buggenhout’s shadowy, somber-hued display provided fascinating fodder for his Mumbai debut, which featured ‘The Blind Leading The Blind’ (2007-8), four ‘dust sculptures’ made of rusty metal and dust. By placing these amorphous objects on pedestals, Buggenhout converted regular irritants on Mumbai’s streets into something seductively strange.

Peter Buggenhout, The Blind Leading the Blind #24 (2008)

It would, however, seem excessively harsh – a ‘dictatorship of art’ in the worst sense? – to declare that only site-specific works can succeed in India; despotism of any kind is likely to generate identikit art. It’s just as unfair for us to insist on a formula for visiting artists to adopt as it is for international curators to expect our cluster of talent to serve as ambassadors for ‘the new Indian art’. (If the Serpentine’s ‘Indian Highway’ had been more nuanced in its selection, it would have granted Indian and western audiences alike more insight into their respective aesthetic journeys.) The answer to the query ‘what counts as international?’ seems to depend on who is doing the judging – or, rather, who holds the power to judge.